hemoglobin

The NAS's Error in Portraying Molecular Biology As Evidence of Evolution

Perhaps the worst of the totally unrealistic claims in the NAS booklet appear in the chapter "New Evidence from Molecular Biology." Once again, the NAS proves in this chapter that it totally discounts all the research and observations over the last 50 years, and supports the theory of evolution in the face of the scientific facts.

Those scientific facts it regards as proof of the theory of evolution in fact bear no such interpretation. The NAS and other evolutionists accept the theory of evolution as a proven scientific fact first, and only afterwards interpret the results of scientific research and observation in the light of that theory. These interpretations are then offered as evidence of evolution. As we shall be seeing in the following pages, such procedures are examples of the circular reasoning employed by evolutionists.

The Error that Molecular Similarities Are Evidence for Evolution

The basic claim of this chapter is that "The unifying principle of common descent that emerges from all the foregoing lines of evidence is being reinforced by the discoveries of modern biochemistry and molecular biology." (Science and Creationism, p. 17). The first example of these proofs in the booklet is nothing other than an assumption produced in the light of evolutionist preconceptions. It is, of course, a fact that the code which translates the nucleotide sequences into amino-acid sequences is the same in all living things, and that the proteins in all living things consist of the same 20 amino acids. The NAS's error lies in inferring from this fact the conclusion that living things descended from a common ancestor. This inference is quite ridiculous. Evolutionists first assume that the theory of evolution is an established fact, and then claim that facts deduced from the theory constitute evidence in support of the theory. However, the fact that all living things possess the same features and functions can also be interpreted as proof of the existence of a common design. There is one Creator Who creates and designs all living things, for which reason it is only to be expected that they all should consist of the same basic features and structures.

The reason why living things possess similar structures and features is that they all have one Creator: The Almighty God.

Myoglobin is not the Evolutionary Ancestor of Hemoglobin

In the chapter "New Evidence from Molecular Biology," the examples of the molecules hemoglobin and myoglobin are cited, and it is suggested that there is an evolutionary relationship between the two. The claim takes this form in the NAS book: "each chain [that make up hemoglobin] has a heme [group] exactly like that of myoglobin, and each of the four chains in the hemoglobin molecule is folded exactly like myoglobin. It was immediately obvious in 1959 that the two molecules are very closely related."

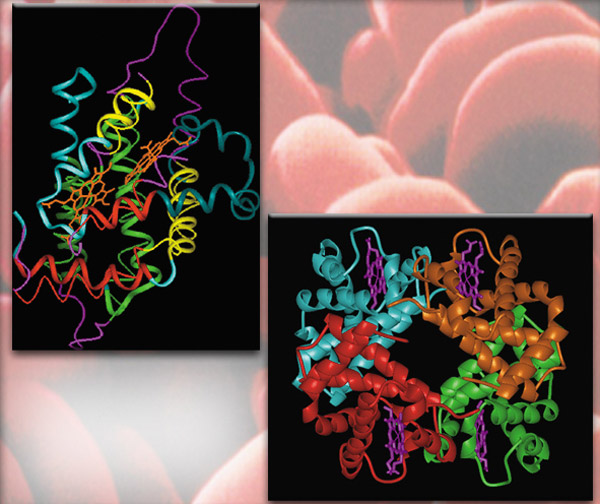

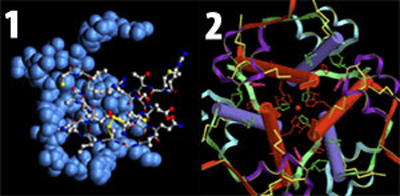

Above: A myoglobin molecule

Right: A hemoglobin molecule

It is true that the molecules hemoglobin and myoglobin possess similar features. What is not true is the suggestion by the NAS and other evolutionists that this similarity constitutes proof that hemoglobin evolved from myoglobin. These claims rest on no scientific foundation and are simply the work of evolutionist prejudice. Let us consider the reasons for this:

It is perfectly natural that vehicles designed for similar purposes should have similar features. For example, every conveyance has a rudder or steering wheel. This principle also applies to proteins with a "common design."

• It first needs to be made clear that myoglobin and hemoglobin are two molecules with similar functions; hemoglobin carries oxygen in the blood, myoglobin takes the oxygen from hemoglobin and stores it in the tissues, providing oxygen to the working muscles. It is therefore very natural that two protein molecules with similar functions should have been designed to have similar properties. To draw an analogy, all transport vehicles possess similar features; they almost all have an engine, a steering wheel, wheels, and special sections to hold cargo or people. It is evident that, because of these similarities, every one of these vehicles was designed for a specific purpose and possesses common features in line with that purpose. Hemoglobin and myoglobin are molecules designed for a similar purpose, for which reason they have similar features.

A food mixer and a concrete mixer were designed for similar purposes.

Despite their different appearances, they possess similar functions and structures.

• When we look at the NAS claim in a little more detail, its impossible nature can be seen more clearly. According to the claim, myoglobin gradually evolved as a result of mutations, differences formed in the amino-acid sequence, and thus the hemoglobin molecule emerged. However, we know that both myoglobin and hemoglobin possess exceedingly complex structures. If either of these molecules is subjected to random factors like mutation, the molecule's function will be corrupted, as we saw in the chapter on mutations, and it will become useless. The disease known as sickle-cell anemia is one example of this. Therefore, to expect a mutation which randomly changes a protein's amino-acid sequence to turn that protein into a more complex one with more features is to believe in the impossible. In order to prove the evolutionist claims, every transitional stage between myoglobin and hemoglobin needs to be functional (and more advantageous than the preceding stage), and that is impossible.

The American chemist Dr. Robert Kofahl, a critic of the theory of evolution, makes the following comment on the impossibility of the claim that hemoglobin evolved from myoglobin:

The structure of a hemoglobin molecule

A good example of alleged molecular homology is afforded by the a- and b- haemoglobin molecules of land vertebrates, including man. These supposedly are homologous with an ancestral myoglobin molecule similar to human myoglobin. Two a- and two b- haemoglobin associate together to form the marvelous human hemoglobin molecule that carries oxygen and carbon dioxide in our blood. But myoglobin acts as single molecules to transport oxygen in our muscles. Supposedly, the ancient original myoglobin molecules slowly evolved along two paths until the precisely designed a- and b- haemoglobin molecules resulted that function only when linked together in groups of four to work in the blood in a much different way under very different conditions from myoglobin in the muscle cells. What we have today in modern myoglobin and haemoglobin molecules are marvels of perfect designs for special, highly demanding tasks. Is there any evidence that intermediate, half-evolved molecules could have served useful functions during this imaginary evolutionary change process, or that any creature could survive with them in its blood? There is no such information. Modern vertebrates can tolerate very little variation in these molecules. Thus, the supposed evolutionary history of the allegedly homologous globin molecules is a fantasy, not science.1

As Dr. Kofahl makes clear, the NAS's claims regarding molecular homology are not science at all, but merely fantasy, like all its other claims.

Moreover, the evolutionists' accounts fail to explain the origin of the myoglobin protein. They say that hemoglobin evolved from myoglobin, but how myoglobin came into existence is still a mystery to them.

Molecular Comparisons Conflict with The So-Called Family Tree

It is suggested in Science and Creationism that an evolutionary family tree can be drawn up by comparing the proteins in living things, such as hemoglobin, myoglobin, or cytochrome c, and that this tree will agree with the paleontological and anatomical facts. This claim is set out in these terms:

[T]he differences between sequences from different organisms could be used to construct a family tree of hemoglobin and myoglobin variation among organisms. This tree agreed completely with observations derived from paleontology and anatomy about the common descent of the corresponding organisms.

Similar family histories have been obtained from the three-dimensional structures and amino acid sequences of other proteins, such as cytochrome c (a protein engaged in energy transfer) and the digestive proteins trypsin and chymotrypsin. The examination of molecular structure offers a new and extremely powerful tool for studying evolutionary relationships. (Science and Creationism, p.18)

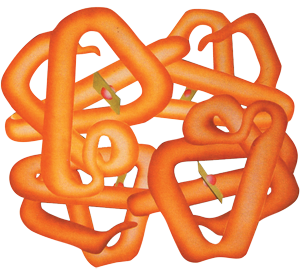

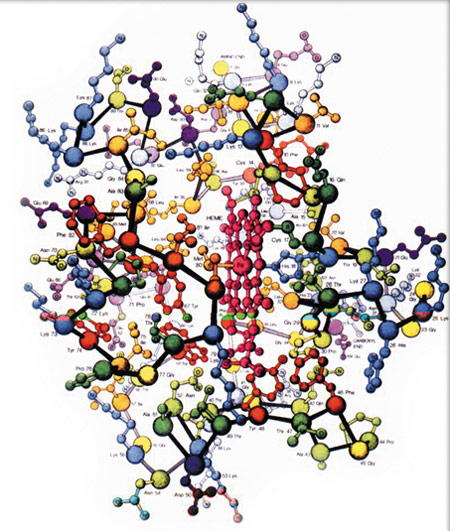

cytochrome c

myoglobin

The so-called family trees obtained from analyses of such molecules as hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome c conflict both with one another and with other data.

It is astonishing that the NAS should make such a claim, ignoring important research and findings in this area. In actuality, comparisons of the molecules cited by the NAS actually represent enormous difficulties for the theory of evolution and reveal its inconsistencies. Before examining the contradictions and errors of the NAS and the theory of evolution in this area, let us provide some information about molecular comparisons.

The protein molecules on which the structures and functions of living things depend consist of amino acids. There are 20 kinds of amino acids in proteins. One particular sequence of amino acids might give rise to a fat-digesting protein in the stomach, while another chain of amino acids might cause an oxygen-binding protein molecule to form. Generally speaking, the amino-acid sequence is the same for the same kind of protein in the same species. However, the amino-acid sequence can change between species. This is the case, for instance, with the hemoglobin molecule, which allows oxygen to be carried in the blood. The practice of comparing the differences in a particular protein molecule between species in order to draw conclusions about evolutionary relationships is known as "molecular homology." For instance, the amino-acid sequences of the hemoglobin molecules in human beings, mice, and horses can be identified and compared. According to evolutionists, the protein sequences of species assumed to have a closer evolutionary relationship should be closer to one another. For instance, the sequences in the hemoglobins of human beings and horses should be closer to each other than to those of rats. Yet, research in this field has revealed a conflict between comparisons at the molecular level and the claims of the theory of evolution. Following are some of the research conclusions that have revealed this contradiction:

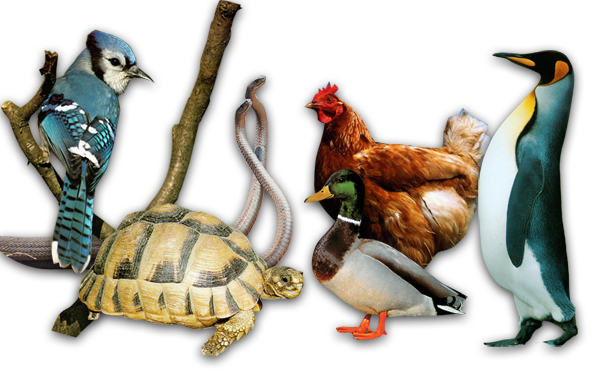

• Comparisons carried out on the molecule cytochrome c, cited by the NAS as evidence for evolution, resulted in disappointment for evolutionists. These comparisons showed that the turtle was closer to birds than to the snake, another reptile. Evolutionists had claimed that the protein sequences of the turtle and snake, two reptiles, should be much closer to each another. 2

•The same research also revealed that chickens exhibit greater similarities to penguins than to ducks. Man emerges as closer to kangaroos than to apes.3

•An article in the January 2002 edition of Popular Science magazine revealed that the DNA of the "grebe," a bird that looks like a duck was found to be resembling a flamingo.4

•As a result of the comparisons of the amino-acid sequence of the hormone LH, amphibians were shown to be closer not to reptiles, as the theory of evolution maintains, but to mammals.5

•In comparisons performed on the alpha hemoglobin protein, it was established that the crocodile and the chicken shared at least 15% of their amino-acid sequences. Next came the viper and the chicken (10.5%). The crocodile and the viper—which, being reptiles, should have had the highest level of similarity—actually possessed a very low level (5.6%). Colin Patterson said that this example had clearly undermined the evolutionists' assumptions.6

•In myoglobin comparisons, crocodiles were seen to have a 10.5% similarity to lizards.

However, the lizard also has a 10.5% similarity to the chicken. In other words, the reptile/reptile level of similarity is the same as the reptile/bird level.7

•In comparisons of lysosome and lactalbumin, it emerged that man was closer to the chicken than to the other mammals tested.8

•Adrian Friday and Martin Bishop from the University of Cambridge analyzed various tetrapod protein sequences. In an astonishing result, human beings and chickens emerged as each other's closest relatives in almost all examples. The next closest relative was the crocodile.9

•Studies on relaxins by Dr. Christian Schwabe, a biochemical researcher from the University of South Carolina Medical Faculty, also produced interesting results:

Against this background of high variability between relaxins from purportedly closely related species, the relaxins of pig and whale are all but identical. The molecules derived from rats, guinea-pigs, man and pigs are as distant from each other (approximately 55%) as all are from the elasmobranch's relaxin. ...Insulin, however, brings man and pig phylogenetically closer together than chimpanzee and man. 10

•In a 1996 study, analyses of 88 protein sequences placed rabbits in the same group as primates, instead of rodents.11 A 1998 study analyzed 13 genes in 19 species of animals, as a result of which sea urchins were grouped with chordates. Another study in 1998 analyzed 12 proteins, as a result of which cows emerged as closer to whales than to horses.12

•As a result of his studies on cytochrome c, Richard Holmquist of the University of California revealed that the biochemical difference between amphibians and reptiles—classes that should be closely related according to the theory of evolution—is greater than the difference between birds and fish, which should be much further apart according to the theory. Indeed, the difference between amphibians and reptiles is even greater than that between mammals and fish or between mammals and insects. The researcher makes the following comments:

In either case, certain anomalies appear in certain vertebrates with respect to the magnitude of these changes and their relationship to time. Such anomalies show up on "phylogenetic trees" as apparently negative rates of evolutionary divergence, or incorrect taxonomic placement of an organism in the wrong family...

... However the difference between the turtle and rattlesnake of 21 amino acid residues per 100 codons is notably larger than many differences between representatives of widely separated classes, for example, 17 between chicken and lamprey, or 16 between horse and dogfish, or even 15 between dog and screw worm fly in two different phyla.13

As the numbers of such studies increases, it becomes ever clearer that comparisons at the molecular level conflict with the theory of evolution. Many evolutionist biologists have had to admit this fact. For example, the French biologists Hervé Philippe and Patrick Forterre admitted in an article in 1999 that "with more and more sequences available, it turned out that most protein phylogenies contradict each other as well as the rRNA tree." 14

The molecular biologists James Kale, Ravi Jain, and Maria Rivera from the University of California wrote in 1999:

…[S]cientists started analyzing a variety of genes from different organisms and found that their relationship to each other contradicted the evolutionary tree of life derived from rRNA analysis alone. 15

Biologist Carl Woese of the University of Illinois, who is renowned for his work on establishing family trees based on RNA-based comparisons, made the following comment on the conflicting nature of his results in an article published in the NAS's Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS):

No consistent organismal phylogeny has emerged from the many individual protein phylogenies so far produced. Phylogenetic incongruities can be seen everywhere in the universal tree, from its root to the major branchings within and among the various [groups] to the makeup of the primary groupings themselves. 16

Biologist Michael Lynch states that the results of analyses of the same genes have been as contradictory as those on different genes:

Clarification of the phylogenetic [i.e., evolutionary] relationships of the major animal phyla has been an elusive problem, with analyses based on different genes and even different analyses based on the same genes yielding a diversity of phylogenetic trees.17

Furthermore, molecular biologist Michael Denton says that comparisons at the molecular level conflict with the theory of evolution:

However as more protein sequences began to accumulate during the 1960's, it became increasingly apparent that the molecules were not going to provide any evidence of sequential arrangements in nature, but were rather going to reaffirm the traditional view that the system of nature confirms fundamentally to a highly ordered hierarchic scheme from which all direct evidence for evolution is emphatically absent. Moreover the divisions turned out to be more mathematically perfect than even most die-hard typologists would have predicted. 18

Basic proteins for life: insulin (1) and relaxin (2).

Dr. Schwabe is a scientist who has dedicated years to finding proof of evolution in the molecular field. He has attempted to establish evolutionary relationships between living things by studying proteins such as insulin and relaxin, in particular. Yet he has had to confess several times that at no point has he been able to obtain any evidence for evolution. In an article published in the journal Science, he states:

Molecular evolution is about to be accepted as a method superior to paleontology for the discovery of evolutionary relationships. As a molecular evolutionist I should be elated. Instead it seems disconcerting that many exceptions exist to the orderly progression of species as determined by molecular homologies; so many in fact that I think the exception, the quirks, may carry the more important message. 19

Professor Donald Boulter, of Durham University's Biological Sciences Department, announced in 1980 that the results of his comparisons of amino-acid sequences conflicted with the assumptions of the theory of evolution:

Initial results obtained by using amino acid sequences of vertebrate cytochrome c led to an outline of the phylogeny of the vertebrates which was similar to that derived from fossil evidence. This very encouraging start was soon to change to a less satisfactory one as the results from other proteins were assembled. Amino acid sequence data sets of different proteins did not always lend themselves to the same phylogenetic interpretation or agree with the accepted phylogeny obtained mainly from fossil or morphological characters.20

An article headed "Genome Data Shake the Tree of Life," written by Elizabeth Pennisi and published in the journal Science, revealed that analyses at the molecular level had shaken the evolutionists' so-called evolutionary tree and that the results were contradictory:

Cytochrome c

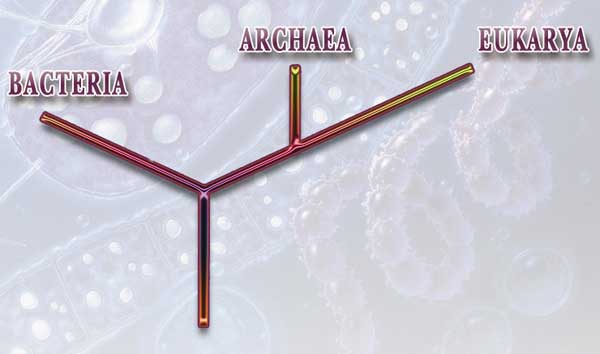

Since then, he [evolutionist Carl Woese] and others have used rRNA comparisons to construct a "tree of life," showing the evolutionary relationships of a wide variety of organisms, both big and small. According to this rRNA-based tree, billions of years ago a universal common ancestor gave rise to the two microbial branches, the archaea and bacteria (collectively called prokarya). Later, the archaea gave rise to the eukarya. But the newly sequenced microbial genomes and comparisons with eukaryotic genomes such as yeast have been throwing this neat picture into disarray, raising doubts about the classification of all of life.21

Pennisi stated that the bacterium Aquifex aeolicus, which lives at a temperature close to boiling point and whose DNA sequence has been unravelled, made concrete the problems facing molecular evolutionists. Robert Feldman, a molecular geneticist and one of the scientists involved in the study of the bacterium, summed up his results at the Conference on Microbial Genome held at Hilton Head, North Carolina, in February 1998: "You get different phylogenetic placements based on what genes are used."22

The article also summarized some of the data which emerged from the research:

The gene for a protein called FtsY, which helps control cell division, placed Aquifex close to the common soil microbe Bacillus subtilus, even though the two supposedly come from different branches of the bacterial tree. Even worse, a gene encoding an enzyme needed for the synthesis of the amino acid tryptophan linked Aquifex with the archaea. That wasn't the only anomaly the Diversa team found regarding the archaea, however. Their analysis of the gene encoding the enzyme CTP synthetase, which helps make the building blocks of DNA, spread the archaea out among all the other organisms evaluated, suggesting that they may not be as coherent and distinct a group as the rRNA tree implies.23

According to the tree based on ribosomal RNA, the evolutionary ancestor split into two branches, archaea and bacteria. Later still, eukarya developed from archaea. Yet, recently sequenced microbial genomes and comparisons with eukaryotic genomes such as yeast conflict with this claim and represent yet another dilemma for evolutionists.

Another scientist whose views were cited in Pennisi's article was the Ohio State University microbiologist John Reeve. He said:

Before, people tended to equate rRNA trees with the [life history] tree of the organism. From the whole genomes, you very quickly come across [genes] that don't agree with the rRNA tree.24

Similarities Do Not Mean An Evolutionary Relationship

Evolutionists suggest a so-called evolutionary relationship between living things on the basis of certain genetic or morphological similarities between them. However, research in recent years has shown that genetic and morphological studies do not represent evidence for the claim that there is an evolutionary relationship between living species.

Same Genes, Different Appearance:

One of the latest studies in this area was carried out by the US National Science Foundation. The research, led by the evolutionary biologist Blair Hedges from Penn State University, compared the genes of aquatic birds. It emerged from this study that birds claimed to be members of the same family actually bore no similarity to one another at all from the genetic point of view. The study summarized its conclusions in these terms:

The genes of aquatic birds have revealed a family tree dramatically different from traditional relationship groupings based on the birds' body structure.1

Molecular comparisons revealed that the nearest relative of the flamingo is a small diving bird with short legs designed for that purpose. This result conflicts with the evolutionary family tree.

Until recently, evolutionists constructed phylogenetic relationships between species by comparing physical characteristics. Thanks to DNA analyses, however, researchers have finally realized that that the evolutionary family trees drawn up on the basis of physical features are invalid.

Among the surprising findings made by researchers was that there is no physical similarity between creatures with very similar genes:

The most startling and unexpected finding of the study is that the closest living relative of the flamingo, with its long legs built for wading, is not any of the other long-legged species of wading birds but the squat grebe, with its short legs built for diving.2

The evolutionary biologist Blair Hedges expressed his astonishment at this surprising finding:

The two species—whose genes are more similar to each other's than to those of any other bird—otherwise show no outward resemblance.3

Same Appearance, Different Genes:

A similar finding emerged with the discovery of a new species of salamander in Mexico. The scientists first imagined that they had found a specimen of a known salamander, but following DNA analysis they concluded that they were mistaken. That was because although the appearance of the soil dwelling salamander they had found was identical to known salamanders, genetically it was very different. The National Science Foundation announced the following conclusion:

The soil dwelling salamander looks identical to one living in mountain foothills several hundred miles away. But DNA analysis by NSF-funded zoologists at the University of California at Berkeley shows them to be a distinct species.4

This led to an astonishing conclusion: despite being identical to each another, the two creatures had to be classified as different species at the genetic level. David Wake of the University of California at Berkeley, the biologist in charge of the research, openly stated the conclusion he had reached: They are not one another's closest relatives.

External similarity does not therefore imply genetic similarity. This outcome is surprising to the experts, because the fact that two species are genetically very different certainly means that they did not evolve from a common ancestor, and that there is no phylogenetic relationship between them.

In the light of these evaluations, the so-called evolutionary relationships assumed by evolutionists based on morphological or genetic similarities have been shown to be invalid. Therefore, all the family trees so far drawn up are without scientific foundation and rest solely on evolutionist preconceptions.

1. Cheryl Dybas, Genes of Aquatic Birds Reveal Surprising Evolutionary History, National Science Foundation – News Tip, August 1, 2001

2. Cheryl Dybas, Genes of Aquatic Birds Reveal Surprising Evolutionary History, National Science Foundation – News Tip, August 1, 2001

3. Cheryl Dybas, Genes of Aquatic Birds Reveal Surprising Evolutionary History, News Tip, August 1, 2001

4. Cheryl Dybas, "New" Salamanders Turn Up from DNA Analysis, National Science Foundation – News Tip, August 1, 2001

The Cytochrome C/Hemoglobin Error

It is claimed in the NAS booklet that the family trees obtained from comparing molecules such as cytochrome c and hemoglobin provide proof of the theory of evolution. According to this claim, the similarities between the amino-acid sequences of these molecules in living things show that they evolved from one another. This claim is totally false. The fact that there are some similarities between molecules like cytochrome c or hemoglobin in some species is no proof that the creatures in question evolved from one another.

First and foremost, it needs to be made clear that, as we have just seen, comparisons performed on other molecules give very different and conflicting results, incompatible with any evolutionist picture.

What biochemists have found with their comparisons of certain proteins like cytochrome c and hemoglobin is this: It is possible to classify species into groups according to their molecular structure. These groups are compatible with the groups produced by comparative anatomy. However, the interesting thing in such a protein "atlas" is that these groups or subclasses are totally isolated from one another. No intermediate forms are to be found between groups—just as there are no transitional forms either in the fossil record or among living groups today. Species are always separated from one another by definitive lines of division.

The Australian biochemist Michael Denton draws attention to the fact that tables such as the Dayhoff Atlas of Protein Structure and Function, which show divergence of the cytochromes, reveal the absence of any such transitional forms in the clearest way possible.25

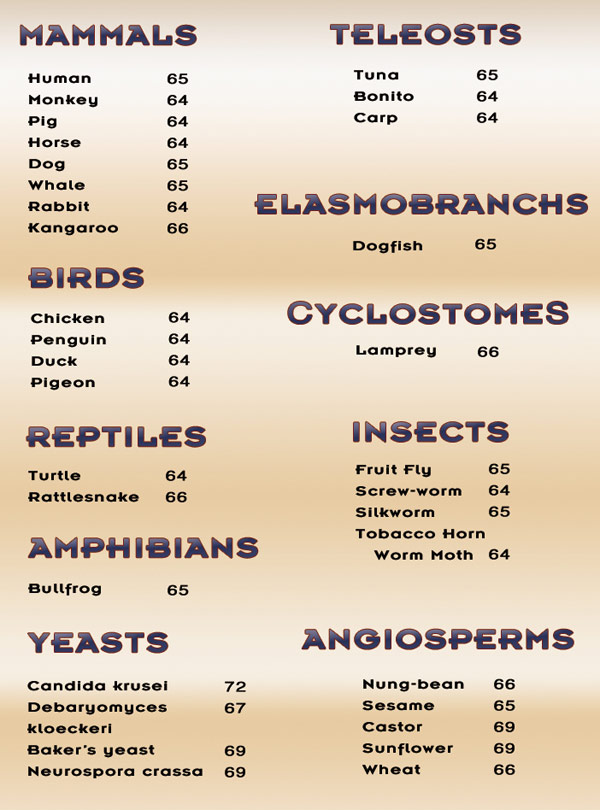

Here is another noteworthy point in this connection: According to evolutionists, the most primitive organisms—those lacking a cell nucleus—are prokaryotes, or bacteria. Higher organisms with a nucleus in the cell, from yeasts to human beings, are known as eukaryotes. If all eukaryotes evolved from bacteria, as evolutionists would have us believe, then one would expect to see a graduated divergence in their proteins such as cytochrome c. Yet, what we actually find is this: the cytochrome c of all the main classes—from human beings to kangaroo, from the fruit fly to the chicken, from the sunflower to the rattlesnake, and from the penguin to baker's yeast—all exhibit the same degree of divergence from the cytochrome c molecules of bacteria (varying between 65 and 69%).

A table listing thirty-three comparisons between bacterial cytochrome c of Rhodospirillum rubrum, and the cytochrome c of other living things. As can be seen from this table, every class is definitively separated from the other classes, and no intermediate forms can be seen at the molecular level. All the sequences of every subclass are equidistant from the members of the other groups. In other words, the molecular sequences of classes that should be more closely related according to the evolutionists' claims are not in reality closer to one another. 26

Michael Denton offers the following comment:

Eucaryotic cytochromes, from organisms as diverse as man, lamprey, fruit fly, wheat and yeast, all exhibit a sequence divergence of between sixty four per cent and sixty seven per cent from this particular bacterial cytochrome. Considering the enormous variation of eucaryotic species from unicellular organisms like yeasts to multicellular organisms such as mammals, and considering that eucaryotic cytochromes vary among themselves by up to forty-five per cent, this must be considered one of the most astonishing findings of modern science.27

What is even more extraordinary is that there is no evidence in biochemistry of the most fundamental evolutionary scheme—the transitions from fish to amphibians, from amphibians to reptiles, and from reptiles to mammals. The protein divergence of land vertebrates like amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, when compared to those of fish, all appear isolated to exactly the same degree. The gradual divergence envisaged by evolutionary sequence is not observed.

From the point of view of their cytochrome c, horses, rabbits, frogs, and turtles are 13% divergent from the carp. Denton says:

At a molecular level, there is no trace of the evolutionary transition from fish to amphibian to reptile to mammal. So amphibia, always traditionally considered intermediate between fish and the other terrestrial vertebrates, are in molecular terms as far from fish as any group of reptiles or mammals.28

As we have seen, the "facts" from molecular biology that the NAS portrays as evidence for the theory of evolution are all either errors or else deliberate distortions by evolutionist scientists.

The Pseudogene Error

Another of the aspects of molecular biology that the NAS represents as proof of the theory of evolution is the sequences of DNA known as "pseudogenes," which are claimed to have no function. (Science and Creationism, p. 20)

As we know, the proteins in an organism's body are produced by means of the information coded in its genes. Pseudogenes are assumed to play no role in the production of protein, or anything else, and are therefore regarded as "functionless."

The concept of pseudogenes is actually part of the "junk DNA" thesis, which maintains that there are parts of DNA which serve no purpose. The fact is, however, that this thesis was revealed to be totally mistaken by a series of discoveries beginning in the second half of the 1990s. The DNA sequences that were alleged to be "junk" were all found, one by one, to perform very important functions in cells and the body. Findings from 1992 revealed that the genes described as junk actually contained vital codes with information about the general structure of the body and about the timing of when other genes should be switched on and off. According to the Washington Post, "Key scientists said the new discoveries were likely to force them to abandon the term 'Junk DNA.' " 29

Then again, even if there really were pseudogenes within the cell, they would still avail the theory of evolution nothing.

The reason why evolutionists regard pseudogenes as proof of descent from a common ancestor is that they consider them to be errors in DNA caused by mutations. They suggest that it is impossible for similar errors to arise in different species, for which reason these errors must have been handed down over the generations throughout the evolutionary process. The fact is, however, that there is a great of evidence to disprove that claim. For example:

1.Some gene regions are more disposed to mutation. It is therefore no surprise that the same gene regions should have mutated in different species, and this does not require descent from a common ancestor.

2.The evidence that pseudogenes, alleged to be functionless, actually do serve a purpose is, as we have seen, increasing day by day.

3.The phylogenetic trees constructed suing pseudogenes both are internally inconsistent and also conflict with other phylogenetic trees.

1.The fact that some gene regions are more disposed to mutations invalidates the evolutionists' claims about pseudogenes. It has been established that there are "popular mutation points" in many genes and pseudogenes.30 This means that some regions in DNA sequences are more disposed than others to undergo mutation, and these are mutations which have no effect on the organism. It is therefore probable that these regions in the DNA of different living things have been subjected to mutation and that the same nucleotides have changed. It is illogical to claim solely on the basis of these similar mutations that these living things descended from a common ancestor.31

2. The evidence that pseudogenes, alleged to be functionless, actually do serve a purpose is, as we have seen, increasing all the time.

The reason why evolutionists portray pseudogenes as evidence for the theory of evolution is that they assume them to have no function. However, as was made clear at the beginning, many pseudogenes believed to be functionless have actually turned out to be nothing of the sort. Evidence of this kind is increasing all the time. Moreover, as some scientists have stated, the fact that these DNA sequences have never been observed to encode proteins in an experimental environment does not mean they lack the ability to do so. Indeed, A.J. Mighell, of the Leeds University Molecular Medicine Department, has this to say on the subject:

In these and other examples it cannot be stated with certainty that a gene is unequivocally either a pseudogene or a gene. It is possible that analysis has not been performed in the appropriate temporo-spatial conditions to detect expression.32

E. Zuckerkandl, G. Latter, and J. Jurka criticize the way in which the claim that pseudogenes have no function is treated as an established fact,

DNA not known to be coding for proteins or functional RNAs, especially pseudogenes, are now at times referred to in publications simply as nonfunctional DNA, as though their nonfunctionality were an established fact.33

In fact, one of the best-known pseudogene groups, Alu, had always been regarded as functionless and was only recently proved to serve a purpose after all.34 It is also thought that some pseudogenes and RNA have a mutual effect on one another.35 Some pseudogenes, it is believed, also have a function as sources of information for forming genetic variety.36

In the nineteenth century, evolutionists produced lists of hundreds of "vestigial organs," which they used as evidence for evolution. This list grew increasingly shorter during the twentieth century, however, when it was established that organs believed to be functionless actually had very important uses for the body. The coccyx is one of these.

It is thought that some parts of pseudogene sequences are copied to functional genes and produce various forms of the functional sequence. This has been reported several times. Examples include the immunoglobins of mice37 and birds38 , mouse histone genes,39 horse globin genes,40 and human beta globin genes.41

Some pseudogenes have been observed to be linked to gene regulation.42 A role of this kind may include competition for regulatory proteins, the production of signal RNA molecules and other mechanisms.43

All these examples are sufficient to undermine the claim that there are "pseudogenes" in living things. A great deal of evidence has now been accumulated with regard to pseudogenes, which shows that the claim that pseudogenes are not beneficial cannot be trusted.

In the nineteenth century, evolutionists produced a list of hundreds of supposedly atrophied organs in the human body, such as the appendix and coccyx, which they claimed had lost their functions during the process of evolution. Thanks to the scientific and technological advances made during the twentieth century, however, the list of so-called "vestigial" organs shrank enormously, and it was realized that organs originally believed to have no function actually possess features of great importance for life. It seems that a similar process is now transpiring with the pseudogenes, and the so-called proofs to which evolutionists have attached their hopes are disappearing one by one.

3. The phylogenetic trees constructed using pseudogenes are both internally inconsistent and also conflict with other phylogenetic trees.

On the other hand, the phylogenetic trees which evolutionists construct using pseudogenes conflict both internally and with other evolutionary trees. For example, a recent article entitled "How Reliable Are Human Phylogenetic Hypotheses?," authored by M. Collard and Bernard Wood and published in the NAS's own publication, PNAS, makes clear that according to the evolutionary tree constructed on the basis of pseudogenes, human beings emerged before chimpanzees and gorillas. However, according to the evolutionists' own claims, the chimpanzee and gorilla emerged before man.44

Of course, inconsistencies of this kind are not peculiar to comparisons made among the human-chimpanzee-gorilla threesome. For instance, an attempt has been made to construct a general primate phylogeny (evolutionary tree) by comparing beta globin molecule data. It was observed, however, that two pieces of data were contradictory.45

Molecular comparisons between human beings, chimpanzees, and gorillas show that man and apes did not evolve from a common ancestor. These analyses invalidate the claims of the theory of evolution.

In another study, Alu sequences revealed that lemurs (a small primate species) and hominids (man) are sibling groups.46 This conclusion, however, conflicts with data which locate the lemur in a different place in the primate phylogeny. The presence of similar pseudogenes in phyla which are regarded as evolutionarily far removed from one another is something evolutionists cannot account for.47 A new example of this is the SINE sequences, a particularly surprising discovery. These pseudogene sequences are shared among living things far removed from each other in evolutionary terms, such as trout48, rodents, and inkfish.49

Some pseudogene sequences are shared by such very different creatures as rodents and ink fish. This is just one of the many examples demonstrating that pseudogenes represent no evidence for evolution.

The contradictions seen in the phylogenetic trees constructed using other molecules can also be seen in those built on the basis of pseudogenes. These facts are quite sufficient to show that pseudogenes do not represent evidence of descent from a common ancestor.50

The Molecular Clock Error and Still More Circular Reasoning

Another phenomenon that the NAS puts forward as proof of evolution is the so-called "molecular clock" (Science and Creationism, p. 19), which was first suggested in the mid-1960s. This hypothesis assumed that a comparison of genetic differences between living species regarded as being close evolutionary relatives, together with the "divergence" periods among living things identified from the fossil record, could be used to calculate a definite "rate of evolution." For example, assuming that all mammals descended from a common ancestor, as well as that the common ancestor of the horse and the kangaroo lived some 70 million years ago, the "rate of evolution" could be calculated by dividing the genetic difference between the two species by 70 million years.

In this way, the average speed of the evolutionary change in a gene or protein became known as the "molecular clock." Evolutionists maintain that the molecular clock reveals when living things began to diverge from one another, thus helping to establish a time frame for such events, as well as evolutionary relationships.

When it was first proposed, this hypothesis was greeted by evolutionists with great enthusiasm as a major trump card to be used against creationists. However, soon afterwards it emerged that it clashed with the data, especially with molecular evolutionary theories and paleontological findings.

Both the numbers and the family trees produced by using the molecular clock are at wide variance with the fossil record. For instance, paleontologists believe that human beings and apes split apart from one another at least 15 million years ago. According to the molecular clock, however, this split should have taken place only 5 to 10 million years ago.51

In more recent periods, as a result of analyses of mitochondrial DNA, which can only be passed down in the female line, it was proposed that modern man was descended from a woman who had lived in Africa as early as 200,000 years ago. Anthropologists rejected this finding, however, because they would then have had to discount all Homo erectus and older fossils that were dated at more than 200,000 years.52

One of the clearest indications that the molecular clock method is unreliable was reported in an article in Science in 1996. The article described how the biochemist Russell Doolittle and his team had used the molecular clock method to propose that single-cell creatures with a nucleus (eukaryotes) split off from those without a nucleus, such as bacteria (prokaryotes), some 2 billion years ago. However, using a different clock, the evolutionist microbiologist Norman Pace suggested that this event took place 3 to 4 billion years ago (even though it is generally accepted that life on Earth goes back no further than 3.7 billion years). On the other hand, the microfossil expert William Schopf rejected both results and claimed that the oldest fossils of bacteria are 1.5 billion years older than the date given by Doolittle. In the face of this claim, Doolittle expressed his doubts as to whether these fossils were real.53 As we can see, the use of the molecular clock produces results that not only are internally inconsistent, but also openly conflict with the fossil record.

In addition, the biochemists C. Schwabe and G. W. Warr state that their analyses of relaxin (a hormone secreted in the final days of pregnancy) are not compatible with the "evolutionary clock model."54

The DNA analyses by the researchers L. Vawter and W. M. Brown produced results that were totally outside evolutionists' expectations; as a result, these researchers call for the molecular clock hypothesis to be totally abandoned:

[The] disparity in relative rates of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA divergence suggests that the controls and constraints under which the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes operate are evolving independently, and provides evidence that is independent of fossil dating for a robust rejection of a generalized molecular clock hypothesis of DNA evolution. 55

Even evolutionist researchers thus accept that the results obtained from the molecular clock are not trustworthy.

Another reason why the molecular clock hypothesis is not to be trusted is that the techniques used to measure the molecular distance between living species are not accurate. Professor James S. Farris of the Swedish Museum of Natural History states:

It seems that the only general conclusion one can draw is that nothing about present techniques for analyzing molecular distance data is satisfactory . . . None of the known measures of genetic distance seems able to provide a logically defensible method, and it appears that some altogether different approach will have to be adopted for analyzing electrophoretic data.56

Farris's criticisms of the techniques in question are widely respected because he himself developed one of the most frequently employed techniques for measuring genetic distance.

Norman Pace

Professor Siegfried Scherer, director of the Institute of Microbiology at the Technical University of Munich, emphasizes the unreliability of the molecular clock in these terms:

Considering the strong demands usually applied in experimental biology, it is hard to understand why the [molecular clock] concept survived such a long period at all. It can neither be used as a tool for dating phylogenetic splits nor as reliable supportive evidence for any particular phylogenetic hypothesis. . . . A reliable molecular clock with respect to protein sequences seems not to exist. . . . It is concluded that the protein molecular clock hypothesis should be rejected.57

In short, the evolutionists' molecular clock does not work. According to Denton, the concept of the molecular clock consists of "apologetic tautologies." Denton criticizes the theory of evolution in these terms:

The hold of the evolutionary paradigm is so powerful that an idea which is more like a principle of medieval astrology than a serious twentieth-century scientific theory has become a reality for evolutionary biologists.58

No matter how much the concept of the molecular clock is given an extraordinary scientific and technical gloss, it is still, as Denton has made clear, the product of circular reasoning and actually explains nothing. That is because in order to construct a molecular clock, one must first accept the claim that living things descended from a common ancestor. Evolutionists first construct molecular clocks on the basis of their preconception, and then use them, just as the NAS authors do, as proof of descent from a common ancestor. Phillip Johnson describes how evolutionists seek to impress people with this theory, which may look very scientific, but is in reality an empty shell:

Darwinists regularly cite the molecular clock findings as the decisive proof that "evolution is a fact." The clock is just the kind of thing that intimidates non-scientists: it is forbiddingly technical, it seems to work like magic, and it gives impressively precise numerical figures. It comes from a new branch of science unknown to Darwin, or even to the founders of the neo-Darwinian synthesis, and the scientists say that it confirms independently what they have been telling us all along. The show of high-tech precision distracts attention from the fact that the molecular clock hypothesis assumes the validity of the common ancestry thesis which it is supposed to confirm.59

As Johnson makes clear, the complex-appearing calculations that so impress people cause them to believe that the molecular clock is a scientific hypothesis that actually illuminates extraordinary truths. The fact is, however, as we have already seen, that the concept of the molecular clock employs circular reasoning, and is incapable of providing any evidence for the theory of evolution. The NAS authors continue this "maybe-they'll-believe-it" logic throughout the chapter in question, setting out their so-called proofs one after the other.

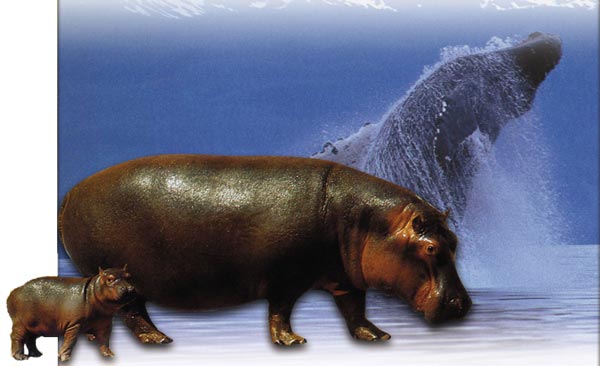

The Purported Evolutionary Relationship Between Whales And Hippopotamuses

At the end of the chapter "New Proofs from Molecular Biology," a claim is made that flies in the face of the scientific facts. The NAS claims that comparisons of certain milk protein genes show that the ancestor of the whale is the hippopotamus, and that this claim is also supported by the fossil record. The truth, however, is that the scientists who actually carried out this research, as well as experts on the origin of whales, do not share the views of the NAS. Scientists at the Tokyo Institute of Technology who carried out the research, which was published in the August 14, 1997, issue of Nature, wrote at the end of their article that the hippopotamus origin of the whale is incompatible with both the fossil record and morphological comparisons:

The conclusions from our retropositional analysis are inconsistent with earlier morphologically based hypotheses. Paleontological and morphological data suggest that modern whales originated from the Archaeocetes (primitive aquatic cetaceans), which first appeared in the early Eocene epoch. The Archaeocetes are believed to have originated from mesonychians [a family of odd-toed ungulates], which appeared before the Eocene. However, the most primitive artiodactyls [even-toed ungulates] (Dichobunids) first appeared in the early Eocene, and the origin of nearly all the families of artiodactyls can only be traced back to the middle or the late Eocene. Such a sequence of appearance of these animals is inconsistent with our molecular data... We believe that recent molecular data will lead to the reinterpretation by palaeontologists of many fossil records of Artiodactyla to match our conclusions. Extensive morphological reversals and convergences, as well as large gaps in the fossil record, will then have to be acknowledged.60

Michel C. Milinkovitch, of the Molecular Biology Department of the University of Brussels, and J.G.M. Thewissen of Northeastern Ohio Medical School, wrote in the same issue of Nature that the Japanese scientists' findings on the origin of the whale conflicted with both morphological and paleontological data, contrary to the claims of the NAS:

The molecular analyses of Shimamura et al.3, reported on page 666 of this issue, further disrupt phylogenetic dogma. Indeed, not only do the authors confirm the close relationship between artiodactyls and cetaceans, but they propose that cetaceans are deeply nested within the phylogenetic tree of the artiodactyls. These results strikingly contradict the common interpretation of the available morphological data (supporting artiodactyl monophyly [common descent]) and, if correct, would make a cow or a hippopotamus more closely related to a dolphin or a whale than to a pig or a camel.61

Furthermore, these scientists acknowledge that this matter is still subject to debate saying:

But the issue is still controversial, because the exact means by which molecular sequence data should be analyzed remains debated.62

Analyses of other molecules have similarly produced contradictory findings. The zoologist John Gatesy states that analyses of sea mammals' blood coagulation protein have presented an evolutionary link between whales and hippopotamuses, but that this conflicts with the paleontological findings.63

As we have seen, the scientists who actually did the research openly state that the molecular comparisons performed in order to discover the origin of the whale conflict with morphological and paleontological findings. The NAS, on the other hand, adopts the opposite point of view, despite that fact that the truth of the matter is well known. It is evident that this is not a question of lack of knowledge, because the NAS claims to be one of the world's foremost scientific institutions. It appears that the NAS is deliberately making groundless claims to convince people with no knowledge of the subject, who have no means of checking the veracity of what they read, or feel no need to, that evolution is true.

We have already examined the invalidity of the evolutionist theses on the subject of the origin of whales in our article "A Whale Fantasy From National Geographic."

(www.harunyahya.com/70national_geographic_sci29.html) As we have explained there in some detail, the thesis that whales evolved from terrestrial mammals is a tale devoid of any scientific foundation. There are considerable morphological differences between the oldest whales and such extinct land mammals as Pakicetus and Ambulocetus, which are suggested as the whale's terrestrial ancestors. On the other hand, the "adaptive processes" proposed by evolutionists for "the evolution of the whale" constitute an unscientific scenario based on Lamarckian reasoning.

Sea mammals possess exceedingly distinct features. To claim that these creatures underwent the dozens of different adaptations necessary for the transition from land to sea as the result of morphological deformities brought about by random mutations is itself a major problem for the theory of evolution. The theory is quite unable to explain how such a transition might have come about. In 1982, the evolutionist science writer Francis Hitching said this on the subject:

The problem for Darwinians is in trying to find an explanation for the immense number of adaptations and mutations needed to change a small and primitive earthbound mammal, living alongside and dominated by dinosaurs, into a huge animal with a body uniquely shaped so as to be able to swim deep in the oceans, a vast environment previously unknown to mammals . . . all this had to evolve in at most five to ten million years—about the same time as the relatively trivial evolution of the first upright walking apes into ourselves.64

Any creature which is suggested as having undergone such a transition would be disadvantaged both in the sea and on land during that process and would be eliminated. The NAS's claims regarding the origin of marine mammals and molecular comparisons are totally based on speculation, and are far from being scientific and rational.

Conclusion

Molecular biology offers no evidence to support the theory of evolution's claim that all the different living categories on earth descended from a single common ancestor by means of random mutations and natural selection. The gradual divergence expected by the theory appears nowhere in the fossil record or molecular analyses.

Michael Denton makes the following comment based on the findings in the field of molecular biology:

Each class at a molecular level is unique, isolated and unlinked by intermediates. Thus molecules, like fossils, have failed to provide the elusive intermediates so long sought by evolutionary biology… At molecular level, no organism is "ancestral" or "primitive" or "advanced" compared with its relatives… There is little doubt that if this molecular evidence had been available one century ago… the idea of organic evolution might never have been accepted. 65

The Nas’s Confessions

Even though the NAS blindly defends the theory of evolution in its booklet Science and Creationism and suggests that there is definitive evidence for the theory in all fields, it has also admitted in its publication Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that the theory contains a number of contradictions. An essay entitled "The New Animal Phylogeny: Reliability and Implications," published in the April 25, 2000 issue of PNAS, is just one of many articles full of such confessions.

Another essay, prepared by scientists from France's Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), details how unreliable and contradictory evolutionary family trees are, and expresses the need for new theories to be produced. The following statements appear in the article:

DNA sequence analysis dictates new interpretation of phylogenic trees. Taxa that were once thought to represent successive grades of complexity at the base of the metazoan tree are being displaced to much higher positions inside the tree. This leaves no evolutionary "intermediates" and forces us to rethink the genesis of bilaterian complexity.

Worst of all, contradictory trees have kept pouring in, often with insufficient critical assessment.

Such a rapid splitting of lineages appears to have occurred repeatedly during evolution, and it renders reconstruction of the order of splits very difficult even with large amounts of sequence data.

The new molecular based phylogeny has several important implications. Foremost among them is the disappearance of "intermediate" taxa between sponges, cnidarians, ctenophores, and the last common ancestor of bilaterians or "Urbilateria."

...A corollary is that we have a major gap in the stem leading to the Urbilataria. We have lost the hope, so common in older evolutionary reasoning, of reconstructing the morphology of the "coelomate ancestor" through a scenario involving successive grades of increasing complexity based on the anatomy of extant "primitive" lineages.66

NOTES

1. Robert E. Kofahl, Creation Essays, "Do Similarities Prove Evolution from a Common Ancestor?;" http://www.parentcompany.com/ creation_essays/essay11.htm

2. Francisco Ayala, "The Mechanisms of Evolution," Scientific American, vol.239, no.3, 1978, p. 56.

3. Francisco Ayala, "The Mechanisms of Evolution," Scientific American, vol.239, no.3, 1978, p. 56.

4. Popular Science, January, 2002; http://www.answersingenesis.org/docs2001/1221popular_science.asp#_edn1.

5. J. King and R. Millar, "Heterogeneity of Vertebrate Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone," Science, vol. 206, 1979, p. 67.

6. Luther D. Sunderland and Gary E. Parker, Evolution? Prominent Scientist Reconsiders, Impact no:108 June 1982; http://www.icr.org/pubs/imp/imp-108.htm

7. Luther D. Sunderland and Gary E. Parker, Evolution? Prominent Scientist Reconsiders, Impact, no:108 June 1982; http://www.icr.org/pubs/imp/imp-108.htm

8. G. Brown, 1998. Skeptics choke on Frog: Was Dawkins caught on the hop? Answers in Genesis Prayer News (Australia), November 1998, p. 3; http://www.trueorigin.org/dawkinfo.asp

9. Mike Benton, "Is a Dog More Like Lizard or a Chicken?" New Scientist, vol. 103, August 16, 1984, p. 19.

10. Christian Schwabe, "Theoretical Limitations of Molecular Phylogenetics and the Evolution of Relaxins", Comparative Biochemical Physiology, vol. 107B, 1974, pp. 171-172.

11. Dan Graur, Laurent Duret, and Manolo Gouy, "Phylogenetic Position of the Order Lagomorpha (rabbits, hares and allies)", Nature, 379 (1996), pp. 333-335.

12. Jonathan Wells, Icons of Evolution, Regnery Publishing Inc., 2000, p. 51.

13. Juke & Holmquist, Evolutionary Clock: Nonconstancy of Rate in Different Species, 177 Science, 530 (1972).

14. Hervé Philippe and Patrick Forterre, "The Rooting of the Universal Tree of Life Is Not Reliable," Journal of Molecular Evolution, 49, 1999, p. 510. (emphasis added)

15. James A. Lake, Ravi Jain, and Maria C. Rivera, "Mix and Match in the Tree of Life," Science, 283, 1999, p. 2027.

16. Carl Woese, "The Universal Ancestor", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 95, 1998, p. 6854.

17. Michael Lynch, "The Age and the Relationships of the Major Animal Phyla", Evolution, 53, 1999, p. 323.

18. Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, pp. 277-278.

19. Christian Schwabe, "On the Validity of Molecular Evolution", Trends in Biochemical Sciences, vol. 11, July 1986. (emphasis added)

20. Donald Boulter, "The Evaluation of Present Results and Future Possibilities of the Use of Amino Acid Sequence Data in Phylogenetic Studies with Specific Reference to Plant Protein," in Bisby, Vaughan and Wright (editors), 1980, pp. 235-236.

21. Elizabeth Pennisi, "Genome Data Shake Tree of Life," Science, vol. 280, Number 5364, May 1, 1998, pp. 672-674.

22. Elizabeth Pennisi, "Genome Data Shake Tree of Life," Science, vol. 280, Number 5364, May 1, 1998, pp. 672-674.

23. Elizabeth Pennisi, "Genome Data Shake Tree of Life," Science, vol. 280, Number 5364, May 1, 1998, pp. 672-674.

24. Elizabeth Pennisi, "Genome Data Shake Tree of Life," Science, vol.280, Number 5364, May 1, 1998, pp. 672-674.

25. Richard Milton, Shattering The Myths of Darwinism, Park Street Press, 1997, p.183.

26. Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, London: Burnett Books, 1985, pp. 279-280.

27. Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, pp. 280-281.

28. Richard Milton, Shattering The Myths of Darwinism, p.184.

29. Justin Gillis, "Junk DNA' Contains Essential Information", Washington Post, Wednesday, December 4, 2002.(emphasis added)

30. Usdin, K. and Furano, A.V., "Insertion of L1 elements into sites that can form non-B DNA", J. Biological Chemistry, 264:20742, 1989. Q. Feng, . et al., Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition, Cell 87:907–913, 1996.

31. R. M. Menotti, W. T. Starmer, D. T. Sullivan, Characterization of the structure and evolution of the Adh region of Drosophila hydei, Genetics, 127:355-366. 1991.

32. A.J. Mighell., "Vertebrate pseudogenes," FEBS Letters, 468:113, 2000.

33. E. Zuckerkandl, et al., "Maintenance of function without selection", J. Molecular Evolution, 29:504, 1989. (emphasis added)

34. L.K. Walkup, "Junk DNA", CEN Tech. J. 14(2):18–30, 2000; K.H. Hamdi, et al., Alu-mediated phylogenetic novelties in gene regulation and development, J. Molecular Biology, 299(4):931–939, 2000.

35. J.R. McCarrey and A.D. Riggs, Determinator-inhibitor pairs as a mechanism for threshold setting in development: a possible function for pseudogenes, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci, USA, 83:679–683, 1986.

36. M. E. Fotaki and K. Iatrou, 1993, Silk moth chorion pseudogenes: hallmarks of genomic evolution by sequence duplication and gene conversion. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 37:211-220; A. Wedell and H. Luthman. 1993. Steroid 21-hydroxylase (P450c21): a new allele and spread of mutations through the pseudogene. Human Genetics, 91:236-240 .

.

37. E. Selsing, J. Miller, R. Wilson, and U. Storb. 1982. Evolution of mouse immunoglobulin lambda genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 79:4681-4685.

38. C-A Reynaud, A. Dahan, V. Anquez and J-C. Weill. 1989. "Somatic hyperconversion diversifies the single VH gene of the chicken with a high incidence in the D region." Cell, 59:171-183.

39. T. J Liu, L. Liu, and W. F. Marzluff. 1987. Mouse histone H2A and H2B genes: four functional genes and a pseudogene undergoing gene conversion with a closely linked functional gene. Nucleic Acids Research, 15:3023-3039.

40. J. Flint, A. M. Taylor and J. B. Clegg. 1988, "Structure and evolution of the horse zeta globin locus," Journal of Molecular Biology, 199:427-437.

41. S. M. Fullerton, R. M. Harding, A. J. Boyce and J. B. Clegg. 1994. Molecular and population genetic analysis of allelic sequence diversity at the human beta globin locus. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences, USA, 91:1805-1809.

42. M. Singh, and G. G. Brown. 1991. Suppression of cytoplasmic male sterility by nuclear genes alters expression of a novel mitochondrial gene region. Plant Cell 3:1349-1362.; Assinder, S. J., P. De Marco, D. J. Osborne, C. L. Poh, L. E. Shaw, M. K. Winson and P. A. Williams. 1993. A comparison of the multiple alleles of xylS carried by TOL plasmids pWW53 and pDK1 and its implications for their evolutionary relationship. Journal of General Microbiology, 139(3):557-568.; Koonin, E. V., P. Bork and C. Sander. 1994. A novel RNA-binding motif in omnipotent suppressors of translation termination, ribosomal proteins and a ribosome modification enzyme? Nucleic Acids Research, 22:2166-2167.

43. T. Enver, 1991. Autonomous and competitive mechanisms of human hemoglobin switching. pp. 3-15 in (Stamatoyannopoulos and Nienhuis, eds.) The regulation of hemoglobin switching. Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Hemoglobin Switching, held in Airlie, Virginia, September 8-11, 1990. Johns Hopkins Press. Baltimore and London.

44. M. Collard and B. Wood, "How reliable are human phylogenetic hypotheses?" Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci, USA, 97:5003–5006, 2000.

45. V. Barriel, "Pan paniscus and hominoid phylogeny", Folia Primatologica, 68:50–56, 1997.

46. E. Zietkiewicz, et al., "Phylogenetic affinities of tarsier in the context of primate Alu repeats", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 11(1):77, 1999.

47. K. Ohshima, et al., "Several short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs) in distant species may have originated from a common ancestral retrovirus", Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., USA 90:6260–6264, 1993.

48. M. Hamada, A newly isolated family of short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs) in Coregonid fishes, Genetics 146:363–364, 1995.

49. K. Ohshima, et al., Several short interspersed repetitive elements (SINEs) in distant species may have originated from a common ancestral retrovirus, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., USA, 90:6260–6264, 1993.

50. B. Farlow, "Stuff or nonsense?," New Scientist, 166(2232):38–41, 2000.

51. Philip Johnson, Darwin on Trial, Intervarsity Press, 1993, p. 99.

52. Philip Johnson, Darwin on Trial, p. 99.

53. Science, vol. 271, January 26, 1996, pp. 448, 470-477.

54. C. Schwabe & G. W. Warr, “A Polyphyletic View of Evolution: The Genetic Potential Hypothesis,” Perspectives in Biology & Medicine, March 27, 1984, pp. 465-471

55. L. Vawter & W. M. Brown, "Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Comparisons Reveal Extreme Rate Variation in the Molecular Clock", Science, vol. 234, 1986, p .194. (emphasis added )

)

56. J. S. Farris, “Distance Data in Phylogenetic Analysis,” Advances in Cladistics, V. Funk & D. Brooks, vol. 3, 1981, p. 22.

57. S. Scherer, "The Protein Molecular Clock: Time For A Reevaluation" in Evolutionary Biology, vol. 24, edited by Hecht, Wallace, and Macintyre, Plenum Press 1990, pp. 102-103.

58. Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, p. 306.

59. Phillip Johnson, Darwin On Trial, p. 99.

60. Nature, August 14, 1997. (emphasis added)

61. Michel C. Milinkovitch, J. G. M. Thewissen, "Evolutionary biology: Even-toed fingerprints," Nature, August 14, 1997, 388, 622 – 623. (emphasis added)

62. Michel C. Milinkovitch, J. G. M. Thewissen, "Evolutionary biology: Even-toed fingerprints," Nature, August 14, 1997, 388, 622 – 623.

63. J. Gatesy, "More DNA Support for a Cetacea/Hippopotamidae Clade . . .," Molecular Biological Evolution, 14(5):537-543 (1997).

64. F. Hitching, The Neck of the Giraffe, Ticknor & Fields, New Haven & New York, 1982, p. 90.

65. Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, pp. 290-91. (emphasis added)

66. "The New Animal Phylogeny: Reliability and Implications," Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences, April 25, 2000, vol. 97, no: 9, pp. 4453-4456.

- Introduction

- The nas's error regarding the origin of life

- The nas's error on natural selection

- The nas's errors regarding mutations

- The nas's errors regarding speciation

- The nas's errors on the subject of the fossil record

- The nas's error in portraying common structures as evıdence of evolution

- The nas's error ın portraying the distribution of species as evidence of evolution

- The nas’s misconception about embryology

- The nas's error in portraying molecular biology as evidence of evolution

- The nas's human evolution error

- The nas's errors in the chapter on creationism and the evidence for evolution

- Creation ıs a scientific fact

- Conclusion