Upon reaching the cell membrane, a substance in the bloodstream does not immediately enter the cell. It is met in different ways, depending upon its size, chemical properties, and whether or not it is beneficial. Any substance about to enter a cell is subjected to tight controls, just like visitors to the borders of another country. If it is a foreign substance, its identity is established and, if it is determined that it represents a threat to security, it is deported. However, the entry and departure of some substances has been made easier, in the same way that countries do for their own citizens. These substances are able to enter and leave the cell without being subjected to any precautionary measures. In short, substances approaching the cell membrane are greeted with different forms of welcome, depending on their identity.

|

| a. transporter protein |

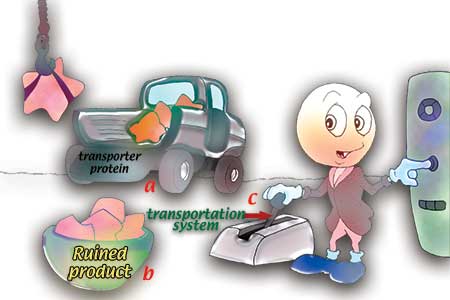

| Figure 136: Every transporter protein is responsible for carrying a different molecule. For example, in the event of the slightest geometrical difference in a molecule's shape, the transportation system will detect this and abandon the molecule, refusing to carry it. |

In order for a substance to be able to pass through the cell membrane, it must be able to mix with the cell membrane—in other words, to be soluble in fat. In the same way that you can never mix oil and water, no matter how hard you try, so it is impossible for a substance that iso insoluble in fat to mix with the cell membrane. A special method is employed for the passage of such substances, and in this, proteins in the cell membrane play a crucial role.

Some molecules are unable to pass through the cell membrane on their own because of their small size. Channel and transporter proteins help molecules and ions to which they give permission to pass through the membrane. The cell membrane’s proteins will transport specific substances and behave most carefully in selecting them. For example, the sugar-transporting system will not transport amino acids.

The transporter protein distinguishes between the two molecules on the basis of their forms and the number of atoms they contain. For instance, two molecules may have the same number of atoms and carry the same chemical groups, but if one has the slightest variation in its molecular form, the transportation system will refuse to carry that molecule (Figure 136).

How is it possible for a transporter or channel molecule to recognize the chemical formula of another molecule and to distinguish it on the basis of the number of its atoms? Could a protein devoid of intelligence and consciousness of its own accord assume a responsibility that will be of benefit to the cell? It is, of course, impossible for these proteins to engage in division of labor of their own accord, to identify beneficial molecules, to assume the job of transporting them inside the cell or to fulfill these responsibilities to the letter as the result of sheer chance. Any rational, honest person will see in these details evidence of the infinite knowledge of Almighty God, the Creator of all things from nothing.