Once, There was the Story of Peppered Moths

Biston betularia, a moth species of the family Geometridae, is perhaps one of the most celebrated species of the insect world, and its fame is due to the fact that it was the main so-called "observed example" of evolution since Darwin.

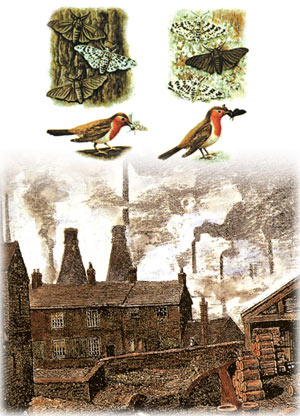

There are two known variants of Biston betularia. The widespread light-colored type called Biston betularia f. typica is a light gray color, with small dark spots that lends it its common name, "the peppered moth." In the mid-19th century, a second variant was observed: dark in color, almost black, it was named Biston betularia carbonaria. The Latin word carbonaria means coal-colored. The same type is also called "melanic," which means dark-colored.

|

In 19th-century England, the dark moths became prevalent, and this coloration was given the name melanism. Based on this, Darwinists composed a myth that they would use consistently for at least a century, claiming that it was a most important proof of evolution at work. This myth found its place in nearly all biology textbooks, encyclopedia articles, museums, media coverage and documentary films about Darwinism.

The myth's narrative can be summed up as follows: At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, in Manchester and other predominantly industrial areas, the bark on the trees was light in color. For this reason, darker, melanic moths landed on these trees could easily be seen by the birds that preyed on them, so that their life expectancy was very short. But 50 years later, as a result of industrial pollution, the light-colored lichens that lived on bark died off and the bark itself became blackened by soot. Now predators could easily spot the light-colored moths. As a result, the number of light-colored moths decreased, while the dark-colored melanic forms, harder to notice on the trees, survived to reproduce.

Evolutionists resorted to the deception that this process was a major proof for their theory; and that over time, light-colored moths had "evolved" into a darker-colored type. According to Darwinist literature, this was evolution in action.

Today, however, like the other classic Darwinist myths, this one has been discredited. In order to understand why, we must look at how the story developed.

Kettlewell's Glued Moths

|

| The photographs of peppered moths on tree bark, published for decades in biology texts, were actually of dead moths that Kettlewell had glued or pinned to the trees. |

The thesis that the melanic form of peppered moths appeared and multiplied in England because of the Industrial Revolution began to be discussed even while Darwin was alive. In the first half of the 20th century, it remained current only as an opinion, because there was not a single scientific experiment or observation to prove it. In 1953, H.B.D. Kettlewell, a Darwinist medical doctor and amateur biologist, decided to conduct a series of experiments to supply the missing proof, and went out into the English countryside, the habitat of peppered moths. He released a similar number of light and dark peppered moths and observed how many of each type the birds preyed. He determined that more dark-colored moths were taken by predators from the light lichen-covered trees.

In 1959, Kettlewell published his findings in an article entitled "Darwin's Missing Evidence" in the evolutionist magazine Scientific American. The article caused a great stir in the world of Darwinism. Biologists congratulated Kettlewell for substantiating so-called "evolution in action." Photographs showing Kettlewell's moths on tree trunks were published everywhere. At the beginning of the 1960s, Kettlewell's story was written into every textbook and would influence the minds of biology students for four decades.141

The strangeness of his assertion was first noticed in 1985 when a young American biologist and educator, Craig Holdrege, decided to do a little more research concerning the story of the peppered moths, which he had been teaching his students for years. He came across an interesting statement in the notes of Sir Cyril Clarke, Kettlewell's close friend, who participated in his experiments. Clarke wrote:

All we have observed is where the moths do not spend the day. In 25 years, we have only found two betularia on the tree trunks or walls adjacent to our traps...142

This was a striking admission. Judith Hooper, an American journalist and writer for The Atlantic Monthly and the New York Times Book Review, reported on Holdrege's reaction in her 2002 book, Of Moths and Men: The Untold Story of Science and the Peppered Moth:

"What is going on here?" Holdrege asked himself. He had been displaying photographs of moths on tree trunks, telling his students about birds selectively picking off the conspicuous ones..."And now someone who has researched the moth for 25 years reports having seen only two moths" sitting on tree trunks. What about the lichens, the soot, the camouflage, the birds? What about the grand story of industrial melanism? Didn't it depend on moths habitually resting on tree trunks?143

This strangeness, first noticed and expressed by Holdrege, soon revealed the true story of the peppered moth. As Judith Hooper went on, "As it turned out, Holdrege was not the only one to notice the cracks in the icon. Before long the peppered moth had kindled a smoldering scientific feud."144

|

| Benjamin Wiker's book |

So, in the scientific argument, what facts became clear?

Another American writer and biologist, Jonathan Wells, has written on this subject in detail. His book Icons of Evolution devotes a special chapter to this myth. He says that Bernard Kettlewell's study, regarded as experimental proof, is basically a scientific scandal. Here are some of its basic elements:

Many studies made after Kettlewell's experiments showed that only one type of these moths rested on tree trunks; all the other types preferred the underside of horizontal branches. Since the 1980s, it has become widely accepted that moths rarely rest on tree trunks. Cyril Clarke and Rory Howlett, Michael Majerus, Tony Liebert, Paul Brakefield, as well as other scientists have studied this subject over 25 years. They conclude that in Kettlewell's experiment, moths were forced to act atypically, therefore, the test results could not be accepted as scientific.

Researchers who tested Kettlewell's experiment came to an even more striking conclusion: In less polluted areas of England, one would have expected more light-colored moths, but the dark ones were four times as many as the light ones. In other words, contrary to what Kettlewell claimed and nearly all evolutionist literature repeated, there was no correlation between the ratio in the moth population and the tree trunks.

As the research deepened, the dimensions of the scandal grew: The moths on tree trunks photographed by Kettlewell were actually dead. He glued or pinned the dead moths to tree trunks, then photographed them. In truth, because moths actually rested underneath the branches, it was not possible to obtain a real photo of moths on tree trunks.145

Only in the late 1990s, the scientific world was able to learn these facts. When the myth of the Industrial Melanism that had been a feature in biology courses for decades came to such an end, evolutionists were disappointed. One of them, Jerry Coyne, said he felt very dismayed when he learned of the fabrications with regard to the peppered moths.146

Rise and Fall of the Myth

|

| Judith Hooper's book |

How was this myth invented? Judith Hooper explains that Kettlewell, and other Darwinists who made up the evolutionist story of the peppered moths with him, distorted the evidence in their desire to find proof for Darwinism (and become famous in the process). In so doing, they deceived themselves:

They conceived the evidence that would carry the vital intellectual argument, but at its core lay flawed science, dubious methodology, and wishful thinking. Clustered around the peppered moth is a swarm of human ambitions, and self-delusions shared among some of the most renowned evolutionary biologists of our era.147

Greatly contributing to the myth's collapse were experiments that a few other scientists did on the subject after it became known that Kettlewell's experiments had been distorted. An evolutionist biologist who recently studied the story of the peppered moth and found it to be without substance was Bruce Grant, professor of biology at the College of William and Mary. Hooper reports Grant's interpretation of conclusions reached by other scientists who repeated Kettlewell's experiments:

"It doesn't happen," says Bruce Grant, of Kettlewell's dominance breakdown/buildup studies [on moths]. "David West tried it. Cyril Clarke tried it. I tried it. Everybody tried it. No one gets it." As for the background matching experiments, Mikola, Grant and Sargent, among others, repeated what Kettlewell did and got results contrary to his. "I am careful not to call Kettlewell a fraud," says Bruce Grant after a discreet pause. "He was just a very careless scientist." 148

|

Other evidence that the evolutionist story of the peppered moths is completely wrong lies in North America's population of Biston betularia. The evolutionist thesis is that during the Industrial Revolution, air pollution turned the moth population black. Kettlewell's experiments and observations done in England were regarded as evidence of this. However, the same moth lives in North America, where no melanism has been observed despite the Industrial Revolution and the air pollution. Hooper explains this situation referring to the findings of Theodore David Sargent, an American scientist who studied the question:

[Evolutionists] ...also ignored the studies on the North American continent that raised legitimate questions about the classical story of dark backgrounds, lichens, air pollution, and so on. Melanics are equally common in Maine, southern Canada, Pittsburgh, and around New York City ...and in Sargent's view, the North American data falsify the classical industrial melanism hypothesis. This hypothesis predicts a strong positive correlation between industry (air pollution, darkened backgrounds) and the incidence of melanism. "But this was not true," Sargent points out, "in Denis Owen's original surveys—which showed the same extent of melanism wherever sampled, whether city or rural area—and hasn't been found by anyone since. 149

With the discovery of all these facts, it came to light that the story of peppered moths was a giant hoax. For decades people all over the world were misled by photographs of dead moths pinned to a tree bark, intended to supply Darwin's missing evidence, and the constant repetition of an old-fashioned story. The evidence Darwin needed to find is still missing, because there's no such evidence.

A 1999 article published in The Daily Telegraph, a London newspaper, sums up how the myth was finally discredited:

Evolution experts are quietly admitting that one of their most cherished examples of Darwin's theory, the rise and fall of the peppered moth, is based on a series of scientific blunders. Experiments using the moth in the Fifties and long believed to prove the truth of natural selection are now thought to be worthless, having been designed to come up with the "right" answer. Scientists now admit that they do not know the real explanation for the fate of Biston betularia, whose story is recounted in almost every textbook on evolution.150

In short, the myth of industrial melanism—like other supposed proofs for evolution, avidly defended by many evolutionists—crumbled.

Once, because of conservatism and lack of knowledge, the scientific world could be duped by tales like that of the peppered moths. But now, all such Darwinist myths have been discredited.

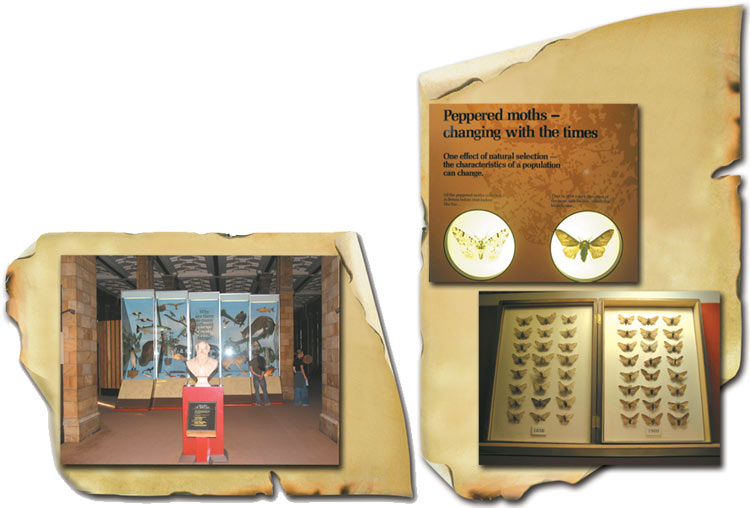

The Fake Moths Still Remain in The Natural History Museum |

|

| Although Kettlewell's account of the "evolution of the peppered moth" has been revealed as totally untrue, Darwinist sources continue to portray this fraud as scientific evidence. These pictures, taken at London's Natural History Museum in October 2003, show that myth of the peppered moth was still on display in the museum's Darwin Centre. |

Footnotes

142-Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, 2002, s.xvii

143- Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men, s.xviii

144- Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men, s. xviii

145- Jonathan Wells, Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth? Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution is Wrong, ss. 141-151

146- Jerry Coyne, "Not Black and White", a review of Michael Majerus's Melanism: Evolution in Action, Nature, 396 (1988), ss. 35-36

147- Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men, s. xviii

148- Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men, s.296

149- Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men, s.293

150- Robert Matthews, "Scientists Pick Holes in Darwin's Moth Theory", The Daily Telegraph, London, 18 Mart 1999

- Introduction

- Darwinism's Crumbling Myths and the Correct Definition of Science

- Once, Life was Thought to be Simple

- Once, the Fossil Record was Thought to Prove Evolution

- Once, There was a Search for the Missing Link

- Once, There was no Knowledge of Biological Information

- Once, It was Believed that There was "Embryological Evidence for Evolution"

- Once, There was the Myth of Faulty Characteristics

- Once, There was the Myth of "Junk" DNA

- Once, the Origin of Species was Thought to Lie in

- Once, There was the "Horse Series" Scenario

- Once, There was the Story of Peppered Moths

- Until Recently, There were Stories of the Dino-Bird

- Conclusion