We are so familiar with seeing, that it takes a leap of imagination to realize that there are problems to be solved. But consider it. We are given tiny distorted upside-down images in the eyes, and we see separate solid objects in surrounding space. From the patterns of simulation on the retinas we perceive the world of objects, and this is nothing short of a miracle.

R.L. Gregory

This important conversation begins on a weekend in a summerhouse outside the city.

MURAD: I really feel I know all of you after reading your letters. It's like we're old friends, meeting after a long absence and just picking up where we left off. You asked just the right questions. In fact, I hope as we talk and share ideas, you'll find the answers are more simple and precise than you can imagine. To explain a few technical matters I brought pictures and diagrams. Now, who's going to ask the first question?

| |

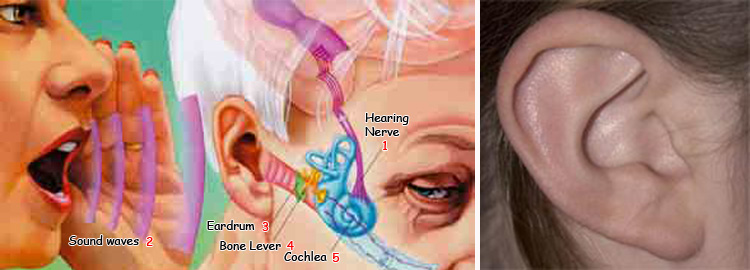

| 1. Hearing Nerve | 4. Bone Lever |

| Even though the process of hearing is regarded as a very natural thing, a complex process is involved as can be seen in the diagram below. Sound waves strike the ear and, after passing through various stages, are converted into electric signals which afterwards reach the brain by way of the nerves. Sounds are perceived in the hearing center of the brain. Actually, the brain is insulated from sound; that is, what we call the hearing center in the brain is a place of complete silence. But, within this silence, we perceive every outside noise and every conversation around us. This is an amazing mystery. | |

IBRAHIM: I'd like to start first since I don't know much about the subject. I've read books that say our lives are only composed of images and we can never be in contact with those images that exist in the external world. Is that true?

MURAD: That's right.

| |

| 1. Lens | 6. Blurred Image 9. Smell Center |

| The light rays coming from the sailboat strike the eye and are converted into electric signals which, after passing through several processes, reach the brain. The image of the sailboat is formed in the brain. | The sense of smell can be understood in the same way. The stimuli coming from an object or from some food are converted into electric signals and, after passing through a series of processes, reach the brain to be perceived in the 'smell' center. |

IBRAHIM: Well I'd like to know what this image is then.

MURAD: IBRAHIM, isn't your specialty biology?

IBRAHIM: Yes.

|

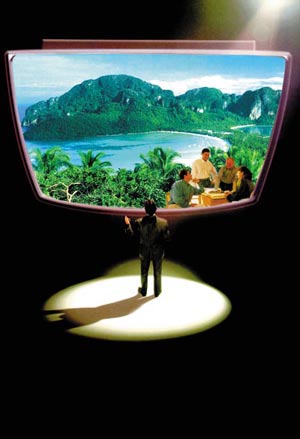

| Someone who thinks that he is sitting and conversing with friends in a bright outdoor place is like someone watching a cinema screen. The friends sitting with him and the vastness of the view he sees around him are images formed in the sight center of his brain. He has no relation with anything outside his brain. |

MURAD: To understand this subject, it's necessary to know how our five senses work. We all remember high school biology but since you, IBRAHIM, are advanced in that science, starting with the sense of sight, can you tell us how the five senses work?

IBRAHIM: Technically speaking, the sense organs are part of a very intricate system that'll take hours to explain. Each organ has its own wondrous system. Volumes have been written about the way the ears make hearing possible, alone. But it's possible to at least outline this complex system in a few words.

What we call external stimuli, that is, an outside effect stimulating our nerve endings such as light, sound, taste, smell and hardness, reach our sense organs – the eye, the ear, the tongue, the nose and the skin. Here the first stage begins: the nerve endings receive the stimulation and convert it into an electric signal that can be transmitted by the nerves. In the second stage these electric signals are carried to the relevant centers in the brain related to sight, hearing, smell and taste. In the last stage, when the brain perceives these signals, it gives the appropriate response.

MURAD: IBRAHIM, you explained it well. Yes, the system works in this way but at the cognitive stage of perception, that is, the stage when we understand what it is we sense, the system becomes much more complex. For example, we're sitting here looking at a pond. The signals of the senses create impressions belonging to the pond and its surroundings... Impressions from the surrounding area such as the smell of flowers, birds singing, the texture of the table and countless elements that form the images come together. The impression is then compared with information stored in our memory and the relevant center of our brain makes sense of our surroundings. Now IBRAHIM, would you tell us what operation takes place when we see that tree over there?

IBRAHIM: It's simple. The information about the tree, that is, its color, distance, and dimensions are carried to my eye by means of light. Inside the eye, this information is converted into an electric signal and fed to the nerves, and then the nerves transport this information to the brain's sight center. These signals reach the sight center and the brain perceives them as a tree.

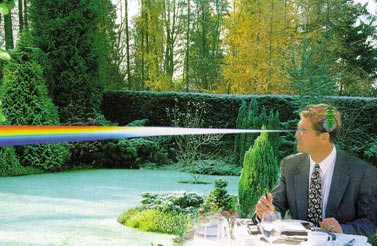

|

| While sitting in a garden, just look around; the trees, the grass, the sun in the sky, the chair you are sitting on, the table you are resting your arms on, the glass you are touching... All these things are actually objects you know by means of your sense organs and perceive by your brain's interpretation of electric signals. |

MURAD: Is the tree you see standing over there now or is it in the brain's sight center?

IBRAHIM: It's in the brain's sight center, of course.

AHMED: Just a minute. Okay, the impression of the tree may be in my brain but the tree is standing over there! I can go and pick a fruit from it or lean against it and sit in the shade.

MURAD: Let's not rush it and look at the subjects in order. Think for a moment about everything that makes a tree a tree – its colors, branches, leaves – all are perceived in the sight center of our brain. When we touch a tree or pick a fruit from it we experience an impression of sight, sound, taste, smell and touch, sent to the brain from all our five senses. We never have a connection with anything outside our perceptions. Without the sense of sight we can't see; if we don't have the sense of hearing, we can't hear. In fact, the things we perceive in our brains by means of the senses make up much of our whole life.

AHMED: Okay I accept that. But look. I'm reaching out and taking a bite of cake and eating it with pleasure. Once I've eaten the cake it gives me energy. Would it be right to say that I have no connection with the reality of this? Can we taste something without having anything to do with its reality?

|

MURAD: In fact, the question was answered earlier in the example of the tree. The cake, the tree and the table are in the cognitive center of your brain. But don't worry! We'll find examples later that'll make this clearer! But to sum it up now; Throughout our lives we taste the savor of the cake that we eat and use the energy that our body inside our brain takes from this cake. Likewise, off a tree that is in our brain we rip a fruit that is also in our brain. And we feel the chill under the shadow of a tree that is in our brain. Everything we know about the world is composed of signals communicated to us by our senses. Apart from the information of those signals carried to the brain, we can never give an answer to questions like, ''What is the reality of these things like?", "Does reality and what we perceive have exactly the same quality?'' It's not possible to go beyond our senses and get outside them. For this reason, throughout our whole lives, the world we see in our brain is perceived by the sense organs. Look, what the famous philosopher Bertrand Russell in his book The Problems of Philosophy emphasizes in situations which results from grappling with this problem.

Before we go farther it will be well to consider for a moment what it is that we have discovered so far. It has appeared that, if we take any common object of the sort that is supposed to be known by the senses, what the senses immediately tell us is not the truth about the object as it is apart from us, but only the truth about certain sense-data which, so far as we can see, depend upon the relations between us and the object. Thus what we directly see and feel is merely 'appearance', which we believe to be a sign of some 'reality' behind. But if the reality is not what appears, have we any means of knowing whether there is any reality at all? And if so, have we any means of finding out what it is like?3

|

| While asleep in your bed with your eyes closed, you can find yourself in a colorful forest and you can feel intense fear as you run away from the wild animals chasing you. Your dreams can be so vivid that you don't know you are dreaming until you wake up. |

AISHA: I can give an example. I'm studying in the computer department, so this subject is a familiar one and I find the topic interesting. In countries where technology is highly developed, a lot of entertainment and education media have been created. And you know computer programs make up a great part of it. These are able to create a three-dimensional image in the brain. Today the principal aim of these 3-D computer games, so fascinating for children, is to give the illusion of real life in an imaginary setting by stimulating the five senses. Education in some professions from NASA astronauts to architects and engineers is done by the use of three dimensional imaging, called simulation. In simulation flight training, a pilot can't tell the difference between real flight conditions and simulated conditions, created by the computer. The subject of many great science fiction films we see is the idea that human life is constituted of impressions or virtual worlds formed in the brain.

IBRAHIM: AISHA's right. The world of science is no different. Ten years ago, no one would even dream of this topic. Now, of course, it's a major theme of discussion. There has been so much work in this area that it's getting easier and easier for a computer to form a non-existent world out of electrical signals and to have human beings experience a desired impression by means of these signals. A great deal of physics, atomic and biological research topics are shaped by this technology.

|

| There is no difference between what we sense in a dream and what we sense while awake. We hear the voices of a crowd; we fall into the sea and experience the excitement as we struggle with the high waves all around us. We experience things as if they were really happening. |

MURAD: You're so right! Developments in technology produce new examples that help people understand this subject more quickly. But I must make it clear that it's easier to grasp this subject by approaching it with an open mind. Even if we didn't know any of the examples you gave, nothing would change because the situation is extremely clear to me. But it's possible that a person who had never thought about this subject before will at first find it a bit strange. To learn that something we have accepted from birth as true, is, in fact, very different from what we have believed it to be, will cause various reactions in people. But if someone's basic aim is to learn the truth, he must accept the truth without resistance. For this reason, the examples we experience every day will assure that we grasp this reality much better. Besides, it's not enough just to explain the subject technically. We must go beyond this and look at the results.

AHMED: I've understood what you said up to this point. But I'm curious about where this subject will lead us. It's a little difficult in a moment to get used to a subject that's so unfamiliar.

MURAD: I think that all of you have understood the situation we find ourselves in. Anyway, it's not so hard to understand since it's a clear truth accepted by science. But since it's necessary for you to come to a definite opinion on this matter, let's look at it again from a different point of view. Now, AISHA, can you tell us about a dream that deeply affected you and that stayed in your conscious memory?

AISHA: Just last night I had a dream that really struck me. I was being attacked by wild beasts in a forest. I was terrified and running as fast as I could along a rough trail when my foot got caught in some brush and I fell. The animals came closer. I ran into a hut, slammed the door and locked it. Now the beasts were trying to get to me from the windows. I picked up an iron bar, trying desperately to defend myself and to escape. At that point I was awakened by a car horn. When I realized it was only a dream, I took a deep breath and was relieved.

MURAD: What's the difference between what we experience while awake and our dreams? Maybe you never thought about that. Maybe it never occurred to you, but dreams will help a lot to understand this subject. Even if a dream is extremely vivid while it takes place, from the moment we immerse ourselves in daily life, the dream loses its clarity and effect. Someone, who woke up in a sweat from a nightmare a little while ago, soon eats breakfast with none of the disturbing feelings his dream evoked. Or a child who is awakened for school in the midst of a pleasant dream quickly forgets the delight of the dream by the time he washes his face.

|

| In this film, a journey is made through different dimensions by means of special images created by a simulator. |

The events in a dream are sometimes so vivid that often, when people awaken, they wonder whether or not the dream was real. In fact, technically speaking, there's little difference between the world we experience while awake and the dreams we have while asleep. In the course of a dream, a person can experience anything that happens while awake; he can talk, eat, breathe, run, laugh, cry, feel pain and so on. The dream world is a copy of the every-day world. Therefore, people react to events in dreams as though they were real. Sometimes they wake up screaming from a frightening dream and don't want to wake up at all from a pleasant one.

AHMED: Last month I had a vivid dream too. In my dream, I was driving along the shore in a motorboat cutting through the water as I went. My friends gathered on the shore, admiring the new boat. I drove faster to impress them. I remember very well the vivid smell of the sea, and the strong wind and cold spray of salty water on my face as the high powered speed boat sped through the water. Occasionally I had to wipe the mist of the seawater spray from my glasses. Suddenly, the boat struck a rock and began to sink. I jumped into the sea and swam to shore with great difficulty. Then I woke up and was sweating profusely. After that dream I wasn't able to get into a motorboat for a while.

MURAD: The events in your dream were very vivid, weren't they? Now try to remember the details of the dream. For example, AHMED, can you distinguish the sounds, colors, smells - and the emotions you felt as you drove the boat – such as fear, hunger and joy from what you experience in a waking state?

AHMED: Probably not.

|

| The hero of the film goes into the simulator and, without going anywhere, he finds himself in a totally different world. |

IBRAHIM: I also had a dream the other day I confused with real life. That evening I wanted to go to bed early because the next day we were going to go to the Islands to have a meal with my family. My sister went to sleep in her own room. Since I was tired, I immediately fell asleep. In my dream, I asked my sister to wash and iron my new shirt. I stood there myself and watched her ironing my shirt. When I got up in the morning, Asra had placed the shirt in the place I wanted, and I wasn't quite sure if it was real or I was dreaming. Had my sister really ironed my shirt or was it a dream? I thought for a minute and decided that it was real, then I went to thank my sister. When my sister acted surprised, I realized that all this had happened in my dream.

MURAD: Yes, sometimes dreams can be so vivid they're confused with real life. Besides, I want to remind you again, there's no difference between what we see while dreaming and what we see while awake. In both states, we have the same reaction to the same stimuli. For example, we sense the full taste while eating, we feel fear and flee from dangerous situations, and feel joy in a happy situation. Although from time to time we experience unusual things, our reactions are the same.

|

| The hero's body is in a twentieth century simulating device, but he finds himself in the nineteenth century. He thinks everything is real, but the cars, the people, his own clothing, even his own appearance are actually composed of impressions projected to his brain. None of them is real. |

AHMED: I totally agree. Even that time in the sea when I was swimming and trying to save myself I remember how cold the water felt.

MURAD: But even more interesting is how it is that we see the things we experience in dreams. IBRAHIM, can you tell us where we see our dreams?

IBRAHIM: Easy. We see dreams in our brain. I mean, just as we experience everything in daily life in our brain's cognition center so do we experience them in a dream. Technically speaking, there's no difference.

MURAD: To this point you've listened to what's been said. So AHMED, tell us: how is it that, at night, with our eyes closed, such a clear and colorful world is formed in the dark recesses of our brain? How does the sun shine, and how are flowers so colorful and the sea so blue? How can we see these things with our eyes closed? Don't we need our eyes to see?

AHMED: I don't have a clue though I know the dream I had seems to be proof of that.

MURAD: Even if we don't receive a stimulus from outside, in other words, even if our sense organs are really unaffected by stimuli belonging to the external world – elements such as light, color and dimension – we can still see and feel. In order for a world to be formed by means of the operation of all these perceptions, we have no need of the signals that our sense organs bring from the outside.

|

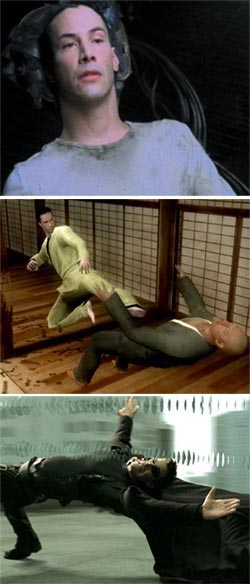

| In recent years, many movies have been made about this reality. The scenes you see above are from just one out of hundreds of such films in which people are connected to a computer and live in a completely different world made up of impressions that seem very real. These films help us to grasp this obvious and important reality which most of us have not considered before. |

MURAD: What sees is not the eye and what hears is not the ear. If all these perceptions were produced artificially and transmitted directly to the relevant center in our brain, we would eat a cake that didn't exist, we would go to a country that didn't exist, we would smell a flower that didn't exist and we wouldn't perceive that all these things were imaginary.

AHMED: Could you go into a bit more detail?

MURAD: As in the earlier example, imagine that you're looking at a tree. There are signals related to the tree that your eyes send to your brain. If we were to artificially produce the same signals, and transmit them to the relevant nerves, we would see the same tree without eyes.

IBRAHIM: The earlier examples of a virtual world explains this matter completely. Look, in order to understand this matter better, let me expand the topic with a few more examples. As you know, with the advance of technology, devices called simulators are used in many fields. A life-like but imaginary environment is created and accessed by the use of a helmet, visor and a glove to make the connection.

|

| Above we see a simulating device. Wearing a special pair of glasses, a person sees unreal impressions and a glove gives him the sense that he is touching things that are not really there. |

IBRAHIM: Those hooked up to the connections can experience an environment as if it was real. In a simulator, the fingers of a person wearing the glove are stimulated by a mechanism which sends signals from the finger-tips to the brain and the person thinks, for example, he's petting a cat. There is a similar mechanism in the helmet. In order that the impression appears more realistic, signals go from the helmet to the person's brain, and as a result, the image of a cat is formed in the brain. The person also hears the sound of a cat. In this way, the appearance, the sound and the feel of a cat are perceived completely. Without there being a single cat to be found, the person really feels that he's petting a cat.

AHMED: Now I understand.

AISHA: Me, too. Just think. If someone came to me while I was having the dream I had, and said, ''Don't be afraid. It's only a dream and not real. What you see is only in your mind and you're safe in bed."

I doubt if I would believe him. Yes, now I understand much better; scientifically there is no difference between what I see in a dream and what I see while awake. It's already common for people to experience computer generated virtual reality. I saw a movie about virtual reality the other day. It was about the same thing we're discussing now.

The heroes of the film were hooked up to a computer, found themselves transported to different places. For example, they thought they were in a gym doing Oriental martial arts but in fact never moved from the chair in front of the computer in that small room. One of the characters tried to explain to the person hooked up to the computer that what he was seeing was really just illusions. The film's hero didn't believe it, and he was only convinced when the computer images froze.

IBRAHIM: I saw that film too, but I didn't think of it from that angle.

AHMED: MURAD, I see the point too, but can you give more examples to help us understand better?

|

| As can be seen in the picture, the hero of the film demonstrates super-human feats when he has to; he can even fly through the air. Although he experiences these things in a highly realistic way, they are actually imaginary impressions created in the brain by the computer. Although the hero thinks he is experiencing these exciting adventures, he is actually sitting in a chair. |

MURAD: Sure! Let's go back to your dream. When you were swimming did you feel the coldness of the water, the buoyancy, taste the salt? While swimming, did you feel the exertion and then the fatigue? And did you hear the sounds of waves, seagulls, and other details your senses picked up during the dream?

AHMED: Yes.

MURAD: Were you convinced that what you were experiencing during the dream was really happening?

AHMED: Yes.

MURAD: Our experience of life in the real world, like the images in our dreams, is even more convincing. The impressions we perceive are so many, so clear and detailed that many people lead their whole lives believing they have some connection with the reality of all they see. But the same thing is also true for your dream as in your dream you thought you had some connection with the sea or the chair where you were sitting. If you think carefully for a moment, you'll understand that the things you experience in your dreams and the life you live while awake are composed of the same impressions.

AHMED: I understand this but when I wake up from a dream, I come back to the real world which is in the same place where it was before I fell asleep. So, it is obvious that there is a world existing apart from our impressions. Right?

|

| In the film, the actor in the leading role is sitting in a chair connected to a computer, as can be seen in the picture above. Nevertheless, he can practice oriental martial arts (as can be seen in the middle picture) and he can move fast enough to outrun a bullet (as in the bottom picture). Everything is so realistic that the actor is very surprised when he opens his eyes and finds that he is sitting in a chair. This proves that to make a person experience a place or a situation there is no need for concrete external reality. |

MURAD: What we call the material world is a place we can never have direct experience of. In fact, we may never know what it looks like. Apart from what our senses pick up and our impressions, we can neither see nor feel matter. From the day we open our eyes, we're always affected by impressions. As far as we know everything that makes up our daily life – school, family, toys, food, a bus, friends, a scenic view, home, the workplace – in other words, everything is composed of a film playing in the brain. Because a person will never be able to get outside of his senses, it's not possible to see what's outside. For this reason, everyone actually lives an entire life relating to impressions of the world that are in his brain.

AHMED: But people go to the moon and I can get on a plane and go to another city. Doesn't that mean that space exists?

MURAD: Basically, ideas such as space, depth, size also form a part of an impression. It's possible to understand this with the help of some simple examples. In your dream, did you see the moon and the stars? Or, as in your dream, did you get in a boat and go for a ride?

AHMED: Yes.

MURAD: The moon and stars in your dream are in the same space as the stars you see while awake. Is that right?

AHMED: Yes, but...

IBRAHIM: Can I answer that? I studied this in an Optics course. What we call space is a kind of three-dimensional seeing. What stimulate the sense of space and depth in an impression are certain factors such as perspective, shadow and movement.

MURAD: True. The kind of impression called space in the science of Optics is part of a very complex system just as the impression of color is, but to put it simply we can say, basically, that an impression that comes to our eyes has only two dimensions. That is, it has height and width. The fact that the dimensions of an impression meet the eye at an angle and that the two eyes see two different impressions at the same time, causes the sensation of depth and space. Every impression that strikes one eye is different from the impression that strikes our other eye from the point of view of elements such as light and position. When the brain brings these two impressions into one picture, we get the sense of space and depth.

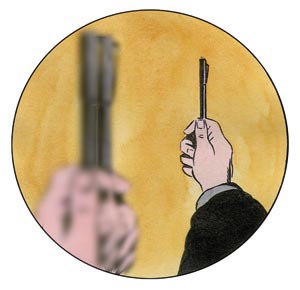

Come on, let's try an experiment in order to understand this better. IBRAHIM will be the subject.

IBRAHIM: Okay.

MURAD: First, stretch out your right arm and show us your index finger. Now, focus your eyes on your finger and open and close your right and left eyes one after the other. Because two different impressions strike your two eyes, you will see that your finger changes place or slides slightly. Now, continue to focus your eyes on your right index finger and bring your left index finger as close as possible to your eyes. You will notice that the finger closer to you has formed a double image which proves that an impression of depth different from that of the farther finger is formed in the system of perception. Now, while you are in that position, if you open and close your eyes one after the other, you will see that the closer finger changes place more than that farther finger because the difference between the two impressions striking the eye has been increased.

|

| In a dream, a person can do everything you see in the picture above: he can talk on the telephone, work at the office, ski, read a newspaper, take a trip, and play with a child. Despite the fact that the person is having a dream, everything seems highly realistic. The same thing is true for the real world. In fact, both what is experienced as a dream and what is experienced as real life are all impressions perceived in the brain. This is an important reality worth considering because we live with it every day of our lives. |

IBRAHIM: Yes, you're right.

AISHA: I did it too. It occurs to me now that the same technique is used in making a three-dimension film. An image shot from two different angles is projected on the same screen. Viewers put on a pair of special color filter or polarized filter glasses. The filters in the glasses receive one of the two images and the brain brings these two together making a three dimensional image. Is that right?

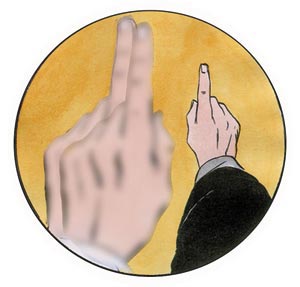

MURAD: Right! Now, let's try another experiment. AISHA, close one eye and look around you. You continue to have an impression of depth, don't you? How is it that a clear impression like three dimensions can be formed on a single, two-dimensional retina? The answer to this lies in the elements of depth that operate when you look with one eye. The way a sense of depth is formed on a two-dimensional retina is very much like the technique used by an artist trying to get a realistic sense of depth in a two-dimensional picture. A few artists are very successful in achieving this sense of depth. There are a few important methods that go into its formation; these are: positioning one object on top of another, the perspective of atmosphere, texture, linear perspective, dimension, height and movement. I brought some pictures to illustrate this.

MURAD: Putting images one on top of the other is an important method of creating the sense of depth. AHMED, it's your turn for an experiment. Now, take one of these two pens in one hand and one in your other hand. Hold them a little distance from your eyes but don't put them on top of each other. Now, move one pen a little farther away and close one eye. Without looking with both eyes, it's very difficult to know which one is farther away, isn't it?

AHMED: Yes, you're right.

MURAD: Now, with one eye closed, bring the two pens close together and place one in front of the other. Now you can measure space and depth much better, can't you?

AHMED: True.

MURAD: The famous American psychologist James J. Gibson was one of the first to understand the importance of change of texture in the sensation of depth. The surface we walk on, a road, or a field full of flowers is actually a texture. The textures close to us are more detailed while those more distant appear indistinct. For this reason, it is easier to make a judgment about the distance of an object which is placed on a texture.

|

| Do not let concepts such as space, size and depth deceive you; you perceive their existence in your dreams also. Just as in real life, you look up at the sky and see the moon and the stars in a particular special relation to yourself; in a dream you see them in the same relation. Actually, they exist in the 'sight' center of your brain. |

AISHA: As you were speaking a sunflower field I saw yesterday came to my mind. Putting all these things together, I understand much better why the field appeared so vast.

MURAD: And when the elements of shadow and light are brought into the picture, the three-dimensional image is complete. For example, the reason we admire a painting is because of the sense of reality and depth, and the use of shadow and perspective. Perspective arises from the perception that things in the distance appear to the viewer as smaller in relation to things that are near. For example, when you look at a landscape painting, the trees in the distance appear small and the trees that are close appear big. Or the image of a mountain in the background is drawn smaller than the image of a person standing in the foreground. In linear perspective, an artist uses parallel lines. Train tracks joining on the distant horizon gives the sense of depth and distance.

AISHA: So it appears that what we call depth and space is an impression formed in our brain.

MURAD: True. You see, because these elements are applied in art and that details come together, a realistic and convincing world emerges, formed from our impressions.

AHMED: You mean like the way we used to watch snowy images on black and white television and not get as involved in the action? Now we go to the cinema and, if the film is well made, we get caught up in it and feel as if it's real. The other day I went with my family to a three-dimensional film about dinosaurs. They gave us each a pair of glasses. The dinosaurs looked so real to me that I reflexively reacted when they jumped out at me. And I couldn't persuade the children that they weren't real.

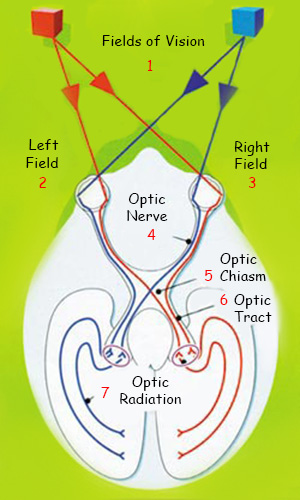

| |

| 1. Fields of Vision | 5. Optic Chiasm |

| As can be seen in the diagram above, the eye receives a two-dimensional image. In the process of seeing, the two images, one in each eye, are formed into one picture. In this way, a three-dimensional image is created. | |

MURAD: Right AHMED. The more intricately the details of an impression are woven, such as light, shadow, and dimensions, the more realistic it appears and deceives our senses. And so we react as if three-dimensional space and depth is real. But every impression is formed on a single surface as on a frame of film. The sight center of our brain has an area of one cubic centimeter; that is, as small as a chickpea. All those things we see in the distance such as far-away houses, stars in the sky, the moon, the sun, airplanes and birds in the air, occur in this small area. In other words, there is technically no distance between an airplane which you may say is thousands of kilometers up in the air and a glass you can reach out and take with your hand. It's all on a single surface in the brain's center of perception.

AHMED: I understand too. There's no longer any doubt that space and depth are particular to the brain just like sight, sound and taste. But what does this change? That is what I can't understand. I mean, what difference does it make if everything is an impression in my brain?

MURAD: Then answer these questions. With what evidence can we claim that we have a relation to a material world outside our perceptions?

AHMED: Give me a moment to think about that. If we look at what we've talked about so far, it seems there's no proof. But there are people who still claim that the concrete, absolute material objects, from which these images arise, exist outside us, aren't they?

MURAD: Yes of course, but AHMED, can you make direct contact with what you call absolute matter?

AHMED: No, I now realize that I can't.

MURAD: Now, consider this. What qualities make that car a material object?

AHMED: Things like the metal used in its manufacture, the colors and then its size and weight.

MURAD: In that case, if we go back to what we were talking about earlier, if we take away from the image of the car our perceptions that have given us the feelings associated with that perception, such as color, hardness, depth, what's left? Or, let me put it this way. If we cut or temporarily interrupt the nerves going from our sense organs to our brains, what do we have?

AHMED: Nothing at all.

|

| In a three-dimensional film, two different images taken from two different angles are projected on the same screen. With the help of special glasses, a three-dimensional image is obtained. Although the viewer does not actually see a three-dimensional image on the screen, technology can give the impression of three-dimensionality. In a similar way, a person is deceived in thinking that he is observing a three-dimensional world around him. |

MURAD: Accordingly, you can never know learn about the matter that Allah has created and that exists outside. Here's a quote from Bertrand Russell that relates to what we've been talking about.

He says, "As to the sense of touch when we press the table with our fingers, there is an electric disturbance on the electrons and protons of our fingertips, produced, according to modern physics, by the proximity of the electrons and protons in the table. If the same disturbance in our finger-tips arose in any other way, we should have the sensations, in spite of there being no table."4

|

|

That is, when you think you're touching your car, it's an impression that comes from the signals sent to the brain by the protons and electrons in your fingertips.

AHMED: From this we understand that the reality of that which we call matter is completely unknown to us.

MURAD: True AHMED, no one can know the reality of matter. Everything called matter is just an impression to us. Our perceptions send us sensations which form impressions such as color, light, taste, smell but beyond these they don't permit us to have direct experience of what we call matter. And science has reached the same conclusion. Those who regard matter as the sole absolute existence are left with no rational, sensible and scientific evidence they can defend in the face of the fact that they can never have direct experience of the original of matter. Because throughout our whole lives we see only mental images and, because our entire world is composed of these images, it's not possible for us to regard anything called matter which exists in a place outside our senses as the sole absoluteness. This is like a blind person commenting about colors; since he has never seen colors he is unable to make any comment. A person trying to make such a description is only assuming.

|

| In these pictures it can be seen how painters give the impression of depth and reality to the picture by the use of shadow and perspective. All of these pictures are on a flat surface but the lines are made so as to give the impression of depth. |

IBRAHIM: MURAD, something I experienced the other day comes to my mind. Two friends and I were in front of our summerhouse watching the full moon with a small, fixed telescope. I said to my friend, "The moon is a beautiful sight. It's amazing that it shines so brightly being so far away. You can see even the craters and mountains on it even thousands of kilometers away." While speaking, my lower eyelid began to itch. When I started to rub it, I saw the moon moving in various directions. I moved away from the telescope.

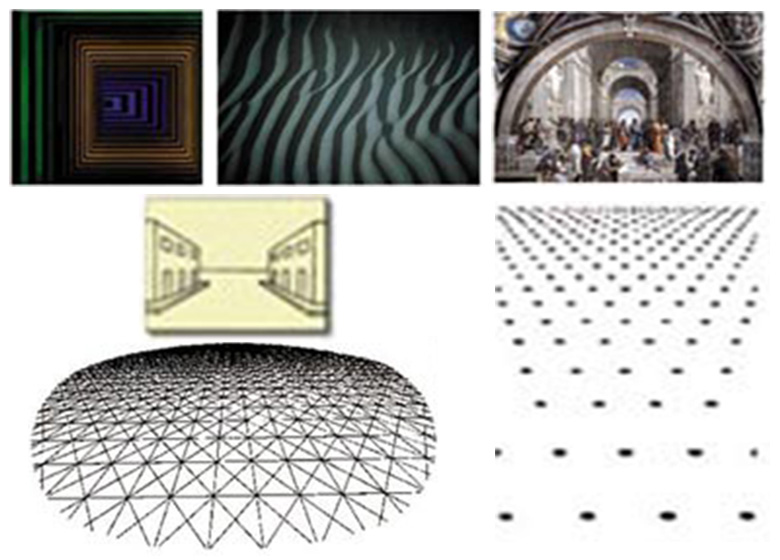

|

| When you look at the pictures above and on the next page, you get a sense of depth and space. For example, in the top picture there are trees close to you and farther away. But this is really a two-dimensional picture and all the trees are located on the same surface. With the use of perspective, an impression of depth has been created. Similarly, we can say that the impressions we relate to throughout our lives are actually on one plane. |

IBRAHIM: With the other eye closed, I continued rubbing my eyelid. The summer houses, my friends, the sea from one end to the other and all the houses in the estate moved in various directions as my eyelid moved. If I were really able to have direct experience of the moon so far away, could the image of the moon I saw be moved so much by such a simple action as rubbing an eyelid? My friends, the shore, the houses in the estate and the sea appeared to be at various distances away. But everything as a whole was moving as a result of the simple action of rubbing an eye. Now I understand that I was mistaken when I thought that I was looking at something outside myself and objects I understood to be in the distance. In truth, the moon, other objects and even me are on the same plane.

|

| In the picture on the left, there is a distance between the person standing and the airplanes over his head. But the glass held by the man on the right appears much closer in comparison to the plane. Actually, both the planes in the distance and the glass in the man's hand are on one surface. There is no distance between the people and these objects. Each image is in the brain's center of cognition. |

MURAD: Very good! Now, let's repeat once more. A person walking on a street is, in fact, walking on a street in his brain and the cars that pass him are in his brain. If we are walking along an empty street and, as IBRAHIM did, gently rub our lower eyelids, we will see this clearly. The street and the trees move in various directions. This is the movement of the impressions in our brains. Just as a picture we are watching on television moves when we try to adjust the antenna, so we have the same kind of effect here. We are like a person in our brain sitting in front of a television: whatever image is being shown, that is what we watch. Whatever we do, eat, walk on the street, go to school, meet with friends, our whole life is as if we were watching a video cassette. Images, sounds, smell, taste and touch are all sensed in the brain. In other words, we experience our outside world in our inside world. We spend our whole lives in the little house in our brain and we watch the outside world on the television in there. We experience all these things in a one cubic centimeter cell in our brain. We lead our lives without ever leaving that 'cell'.

IBRAHIM: For example, the fact that a person who is color-blind sees the world in different colors is proof of this, isn't it?

|

| If a computer is connected to the brain and electric signals are transmitted from the computer to the brain to create the sense of touch, even if there is no actual act of touching, the person thinks that he is touching something. Such a sensation is easily created with a simulator. |

MURAD: I think you understand this subject very well. Yes, as you said, because a person watches these images throughout his whole life, he perceives the world according to the perceptions that are given to him. If the sense organs are damaged, a distorted perception occurs; for this reason, a person who is color-blind cannot know real color. People with a seeing disorder sees a blurred world.

AHMED: I understand.

MURAD: A person cannot get outside these impressions throughout an entire life. Therefore, to claim that the things we see are the way we see them and to think that we have any connection to their reality is illogical and of no use.

IBRAHIM: MURAD. There's something I want to ask. Are there many people who know about this subject either in the past or in the present?

MURAD: There are countless people. Not only in the world of ideas, but people working in scientific fields such as physics, atomic theory and astronomy, and well-known scientists whose names we often hear have understood this subject in one way or another and have come to their own interpretations. Materialist thinkers such as Marx and Lenin also studied this subject in their day and understood that it posed a great threat to their materialist views. For this reason, no matter how well they knew the truth, they tried to take measures to suppress it as they realized that accepting such a view would not be to their own advantage. If you like, I will give you the relevant sources. You do some research and tomorrow we'll talk about what you've learned.

|

| According to Ibrahim's example, when a person looks at the moon, the telescope or the view in front of him, he is actually looking at images on the same plane. However, these images can lead a person to believe that they are in different spaces. If you looked at such objects disposed in space and scratched your lower eyelid as Ibrahim did, you would see that the objects do not remain fixed but change their location. |

ADNAN OKTAR: Allah says, "I am the wealthy One. None of you has any possessions." We look inside our brains. The possessions we form with our eyes come and go. But we see we have no other possessions in our brains than an image. We look at money and put it on the table. The money we produce through our eyes comes and goes. Money is an image in our brains. Gold is also an image. Houses and cars are all images. That is why Allah says, "You have no possessions. You are poor." Do you know how poor? Infinitely poor. "You have nothing," says Allah. 'You are needy," He adds. He says that "Allah is the Al-Ghaniyy, He Who has no need of anything." He says it is He Who gives us these images.

PRESENTER: If this is an image, how is it I am touching it?

ADNAN OKTAR: You have now perceived it in your brain. You feel it in your brain. You feel it at your finger tips. In other words, because of the image, because it is three-dimensional, when it and the image of your finger are combined together, since they are all perceived in the same place in the brain, you feel a sensation stemming from three-dimensional perception that you are touching it with your finger. There is not feeling in your finger tip. Not in that sense. The only feeling is in the brain. For example, you see my image. I appear to be at a distance, though we are in the same place. It is as if your microphone and mine are in the same place. We form in the same place in your brain.

PRESENTER: Why do we both see you as being in the same place then? How do we see you the same?

ADNAN OKTAR: We do have the reality of external matter, but it is transparent on the outside. The transparency stems from its atomic structure. But there is pitch darkness. There is no darkness on the outside. There are photons. We perceive photons as light. There are sound waves on the outside, waves. Our brain is like a radio. The waves come into our brains and turn into sounds in the radio in our brains. The ears in our brains hear. These ears are all deaf. Both ears, they are just tools. Ears are tools that convert vibrations into electricity. They are devices that convert sound waves entering from the outside into an electrical current. One certainly does not hear in the ear. It is the same with the nose. People do not smell with their noses. It just converts gaseous chemical substances from the outside into electrical energy and transmits this to the brain. We smell in our brains. In other words, we smell a rose in our brains. The image of the rose on the outside is black, dark and transparent. Even if there is light it is transparent. That red and green color therefore forms in the brain, and is a perception. There is not one scientist who does not agree with this. Irreligious people, atheists, Buddhists, Muslims and Christians all agree on this. It is a scientific reality. (Ekin TV, 11 January 2010)

ADNAN OKTAR: We are in the age of Hazrat Mahdi (pbuh) in the End Times. Rasulullah (May Allah bless him and grant him peace), the Speaker of truth, says this will happen. And so it will. But in 10 years' time. People's brains and souls will change entirely after 2012. They will enter another world and have a whole new perspective. Many people have taken this as the Day of Judgment. It is in writings dating back to before Christ. 2012, or the Day of Judgment, he says, is when there will be a fundamental change in the human soul.

PRESENTER: What kind of change?

ADNAN OKTAR: People will see the truth about matter. They are currently ignorant of the truth about matter. For example, I am seeing you now. You are forming in a tiny space in my brain, but the image is so sharp and vivid that you genuinely seem at a distance from me. The image really seems to be at a distance. For instance, you are currently appearing in my brain. A small thing, you appear like a human being and that is enough for me, and it all happens in this tiny space. For instance, there is bright light in the brain, but no light on the outside, in the outside world. And I am sitting in my brain, as if in an apartment block, watching you through my eyes. People will of course come to realize this. Not everyone can understand it now, even if I talk about it. There is no sound on the outside, for example. Sound is an interpretation by the brain, something unique to the brain. It is the interpretation by our souls in our brains. Sound; there are waves on the outside, but that is all. People imagine there is a glorious noise on the outside. But there is not a peep, no sound at all. All sound is perceived by the soul in the brain, and the brain interprets those sound waves as sound. The same with visual images; our eyes do not see. They seem to see, but our eyes do not. Our eyes are cameras, cameras made of flesh. They focus light rays onto a specific point, and that chemical energy is converted into electrical energy there. They take that electrical energy and transmit it to our brains. This is a marvelous system of course, but that is a separate matter. Our souls see that electric current as the world. A very low voltage electric current passes through that flesh using no wires, and this very sharp three-dimensional image forms... People's minds will open up fully as of 2012 and this will be seen very clearly. (Adıyaman Asu TV, 23 November 2009)