|

| The seahorse is the only species where the male becomes pregnant. The male seahorse carries its eggs in a pouch under its belly for many weeks. |

The male seahorse has a brood pouch wherein he keeps the eggs he receives from the females. She deposits her eggs into the brood pouch of the male, who keeps them there until they develop into tiny little seahorses. Here they are fed with fluid from a placenta-like structure, and oxygen is supplied them by the capillaries. Depending on the species, this pregnancy lasts between 10 and 42 days. During this time, the female visits the male every morning. These visits and greeting rituals give the female an idea about her mate's due date and in this time, the female prepares to produce new eggs.67

The grunion, unlike other species of fish, buries its eggs on land because its eggs can develop only in such an environment. For the grunion, leaving the water for even a short time means death. Yet they must do so, or else their lineage will terminate. These fish, acting according to God's guidance, come ashore at the right time and when conditions are just right to bury their eggs in the sand. They wait for the full moon, because then the tides are bigger and waves can reach further up the shore. They await the high tide, which lasts for three hours, and then come ashore with the biggest wave they can ride. The females that succeed in coming ashore this way, skillfully wriggle into the sand and spawn approximately 5 cm (2 inches) under the surface.

Their danger has not yet passed, however, since they still must return to the sea. They have to complete spawning and bury their eggs in the sand before the tide withdraws. If they miss this opportunity, they will die on the dry shore. As we see, these fish expend much effort into the correct placement of their eggs and run a great risk—but at the same time, acting intelligently.68

The dangers the grunion faces and the intelligent behavior it displays, both reveal that there is a mind and consciousness outside of this little fish. There are many easier methods of spawning, yet it prefers to bury its eggs in the sand on shore. Let's presume that it acquired this habit through a series of chance events. What would happen, according to this scenario? The female would die at the first hurdle—trying to come ashore to bury her eggs. She would face prohibitive conditions, making it impossible for her to learn by trial and error—much less pass her "learning" along to the eggs, already in her body! God makes the grunion's eggs able to develop in the sand, as well as inspiring the fish to choose the right time to come ashore and thereby, reproduce and survive.

The female bowfin spawns between May and June. In this time, the dark spot on the top of her tail fin becomes more pronounced. The male bowfin prepares an underwater nest in shallow, weedy areas by tearing loose the stems and leaves of plants, leaving a small circular clearing surrounded by vegetation. When the female releases her spawn, the eggs stick to the bottom of the nest, and the male stays to guard them, swimming in circles to create a current that increases the oxygen flow. The male fish continue to protect its offspring until they reach a length of approximately 10cm (4 inches).69

Another Creature That Migrates Vast Distances to Reproduce:

| Blennies Fanning Their EggsA female blenny will stick her eggs under rocks, in crevices, or on the inside of bottles she finds on the seabed. Then, the male starts guarding the eggs and fans them to increase water circulation and thereby, constantly provide the eggs with oxygen.70 |

Salmon's Arduous Journey to Reproduce: | |

| |

| Migrating salmon. | Salmon swimming against the current. |

| These fish spend the first five years or so of their lives in the open oceans. During this time, they develop their muscles, store fat and grow big and strong. Those that mature toward the end of this five-year period will need every bit of the calories stored in their bodies, because in order to reproduce, they need to return to the fresh-water rivers where they were hatched. Salmon have a long journey to reach the place where they will spawn their next generation. Once in the river, they have to swim against the current and force their way up waterfalls. Salmon stop feeding when they enter fresh water. The final leg of their journey consumes almost all their stored energy. Once they have spawned, their strength and endurance are at an end, and the exhausted fish die.71 For this act of selfless, virtually suicidal behavior by the salmon in order to reproduce, there is only one explanation: This fish is obeying the rules God made for it. For a salmon to return to the same river where it was spawned, for it to calculate the proper time, and never abandon the journey even in the face of hostile conditions—no fish would do this by its own willpower. No fish could show so much premeditated, noble and selfless devotion on its own. | |

Every year in December and January, pregnant grey whales leave the icy waters of the Arctic Ocean and migrate towards California, passing by North America's western shoreline, seeking out temperate waters to give birth. On this journey, interestingly, the whales do not feed. But, they are well prepared, however, since throughout the summer, in the krill-rich waters of the north they've been building up stores of energy in the form of thick layers of blubber. As soon as the grey whales reach the tropical waters of western Mexico, they give birth. The baby whales feed on their mothers' milk and build up their own stores in preparation for the journey back to the northern hemisphere in March together with the other grey whales.72

|

| The safest place for a baby cichlid is in the mouth of its mother. |

Both male and female cichlids take good care of their spawn and young. At all times, one of them is fanning the spawn with its fins from above. They alternate in this duty, once every few minutes, in order to increase oxygen flow for the better development of the eggs and also to prevent fungal spores from settling and developing on the spawn.

The cichlids' care serves mainly to keep their spawn clean, which is why they eat their unfertilized eggs, to prevent contamination of the healthy ones. Later on, they transfer their spawn to holes they made earlier in the sand, carrying a few eggs at a time. While one fish goes to the hole, the other guards the rest of the eggs, and this continues until all have been moved. Once the young emerge, the parents keep on protecting them. The young stay close together, and if one of them should stray, one parent brings it back in its mouth.73

The cichlid is not the only creature that's sensitive about cleanliness. For instance, the female centipede regularly licks her eggs clean in order to prevent fungal spores from attacking them and curls her body around them, protecting the eggs against predators until they hatch.74

The female octopus releases her spawn into cavities in rocks, then guards it and frequently cleans them with her tentacles and rinses them with clean water.75

For creatures on the African continent, the hot sun can often be deadly. To protect themselves from its rays, many animal species seek out places in the shade. But the South African ostrich is more concerned about shielding its eggs and offspring from the intensity of the sun. For this reason, it stands above its eggs and later, its hatchlings, spreading its wings to provide shade for them.76 Meanwhile, it exposes itself to the sun, proving its dedication.

|

| Many species of bird shade their eggs or young. Various examples of this selfless behavior are shown here. 1. 2. 3. Right and bottom: Ostriches provide shade for their eggs and offspring. 4. A stork species native to Zambia shades its young. |

The female of this species lays her eggs into a concave silk cocoon which she has spun for just this purpose. She sticks this cocoon to her lower abdomen and takes it wherever she goes. If it falls loose, she will stick it back onto her abdomen.

Once the young spiders emerge from the eggs, they will stay for some more time in her cocoon and, when the time is right, climb onto her back. The female carries her young around with her. In some species, the young are so numerous that they pile up high on her back. As far as we know, the young do not feed during all this time.

A different species of wolf spider removes the cocoon from her body in June or July, when the eggs are about to hatch. She then spins a tent over it and guards it. After hatching, the young remain in this tent, shedding their skin twice until they are fully developed. Then they disperse.77

How can an invertebrate like a spider show loyalty, interest, compassion and patience? This question provides food for thought.

|

| This female spider carries her eggs and offspring in a silken cocoon, which is proportionately too large for the her body. To be able to carry it, she is forced to walk on straightened legs. When the eggs are about to hatch, the female weaves another cocoon to protect her offspring. Emerging from the old cocoon, the young move into the new one, where their mother protects them. |

| In Arizona's Sycamore Canyon, a male giant water bug (Abedus herberti) carries its eggs on his back. The eggs are stuck onto his back by the female. This is another species where the father cares for its offspring and it does his best to keep the eggs well ventilated and moisturized.78 |

Water bugs face a real dilemma. If they deposit their eggs above water, they will dry up; if they lay them in the water, their grubs will drown when they emerge from the eggs. The male bugs shoulder the responsibility of keeping the eggs laid above water, moist and ventilated.

The female giant water bug, Lethocerus, lays her eggs on a branch afloat on the water. The male bug dives into the water frequently and then climbs up on the branch where he lets water drip on the eggs and also keeps predatory insects away.

The female giant water bug Belostoma (often found in swimming pools) attaches her eggs with a sticky substance onto the male's back. He swims on the surface, airing the eggs, pedaling backward and forward with his hind legs, doing push-ups or holding onto a branch, and sprinkles water onto the eggs for hours on end.

Three different species—Bledius rove beetles, Bembidion ground beetles, and Heterocerus—all have an interesting method of preventing their eggs from drowning on tidal mudflats. They plug their narrow-necked brood chambers when the tide is coming in and unplug them again when water recedes.79

That even insects can show such foresight and protect their eggs intelligently once again shows the clear reality of creation.

|

| This bug from Australia protects its eggs carefully, hanging them on the branch of a tree and never leaving them unattended. |

|

| The digger wasp puts great effort into the burrow it digs for the young it will never see, and stores in there the food it will need. |

The digger wasp digs a slanting burrow for its larvae to grow in. This is a difficult task for such a small creature, but the wasp first lifts the soil with its jaw and then throws it behind with its front legs.

This wasp has another important ability:It digs its burrow without leaving a trace around it. Trapping soil between its jaws, it removes it bit by bit and deposits it at some distance away from the burrow without forming piles anywhere, so as not to draw the attention of predatory insects.

When the hole is enlarged to the size of the wasp's body, it excavates a nursery chamber just big enough for its egg and a supply of food. It then covers up the entrance temporarily and goes hunting for insects.

Each species of digger wasp specializes in hunting for caterpillars, grasshoppers, or crickets. When hunting for its young, it will not kill its prey, but paralyze it with its sting and drag it back to its burrow. There, it deposits a single egg onto the prey. The insect remains alive and fresh until the egg hatches and the larva begins to feed on it.

Once the wasp has arranged the nest and food for its young, it's time to cater for the larva's safety. Carefully it conceals the entrance with soil and little pebbles. It picks up a little pebble with its jaws and uses it like a hammer to drive the soil level with the ground. Then it rakes the surface with its spiky legs and sweeps the ground until the burrow's entrance is perfectly concealed. But this is still not good enough for the wasp! As a precautionary measure, it digs a few dummy burrows nearby. In this enclosed and well-protected burrow, with the food it has, the larva will develop into an adult and can then emerge by itself.80

The wasp will never see its young, but nevertheless prepares with due care and attention everything the larva will need. All this patience and hard work reveals dedication, foresight and careful thinking. It is obvious that this tiny creature cannot possibly do all this by itself and must be enabled to do so by a knowledgeable, intelligent power.

As mentioned before, evolutionists say that animals are programmed to behave in this way. According to their theory, this program originated in a series of random occurrences. If we consider the extraordinarily complex features of living things, it becomes obvious how irrational and illogical this claim really is. Anyone of thought and conscience can easily recognize that all creatures act on God's inspiration.

| "He is God—the Creator, the Maker, the Giver of Form. |

|

All Baby Animals are Created with a Cuteness that Inspires Compassion |

|

| Compared with their adult counterparts, the young of most species are more lovable in their appearance and behavior. They display more rounded features, outsized baby-eyes, full cheeks and pronounced forehead—all responsible for this perception. In some species, the young are even of a different color than the adults. For instance, the fur of a baby baboon is black and pink, whereas the adult's is olive. The baboon community perceives these young animals as more appealing than their other, older counterparts. Some females have even been observed trying to kidnap appealing youngsters from their mothers. This behavior disappears when the young baboons' fur turns from its original black and pink to the same color as the adults'.81 |

Young animals are often born totally dependent on their parents' care and protection. Creatures born blind or naked, unable to hunt for themselves, will usually die of hunger or cold if not taken care of and protected by their parents, or by other adult members of the herd. However, animals act on God's inspiration and therefore, feed and protect their young at any cost.

When it comes to protecting their young, animals can be quite vicious and dangerous. If they sense danger or come under attack, usually they prefer to flee the area with their young. But if not, they will throw themselves at the attacker without hesitation. For example, birds and bats are known to attack naturalists who remove their young from their nests.82

When hoofed animals like zebras are attacked, they split into groups, gather their young into the center, and run for their lives. If cornered, the adult members of the herd defend their foals bravely against the predators.

When giraffes are attacked, they shelter their young under their bodies and kick out at the attacker with their front legs. Antelopes and deer are timid, nervous animals who choose to run if they have no young to protect. But should foxes or wolves endanger their offspring, they do not hesitate to use their sharp hoofs.

Smaller, weaker mammals prefer to conceal their young or take their offspring somewhere safe in order to protect them. If they lack the opportunity to do that, however, they can become very aggressive to scare away any attacking predator. For example, the cottontail rabbit—ordinarily a very timid animal—takes great risks to drive enemies away from its young. If its young are attacked, it will run back and kick out at the enemy with its powerful hind legs. This bravery is often enough to drive even stronger predators away from its burrow.83

When predators are chasing a young fawn, the mother gazelle gets behind her young, because predators usually catch their prey from behind. She will try to stay close up behind the fleeing fawn, and if the predator comes close, she will try to divert it away. She will use her hoofs against jackals or run close by the predator to draw attention away from her young.84

Some mammals' colors blend in with their environment. Sometimes, however, the young need to be guided by their mothers in order to take advantage of this feature. A mother deer will use her young's camouflage as an advantage on its behalf. She hides her young among the undergrowth and makes it stay there. The fawn's brown fur with white spots keeps it from being spotted when seen from even a close distance. The white spots in the fur give the impression of dappled sunlight falling on the undergrowth. Predators passing even only a few meters away will not spot the fawn. The mother will be close by, but won't do anything to draw attention to her youngster's location. Very cautious, she will visit her young only to nurse it. Before returning to the forest, she will budge her young to get it to lie down again. Even if the young gets up every now and then, it will immediately drop to the ground again if it hears any unfamiliar sound. The young animal hides this way until it grows big enough to run with its mother.85

|

|

|

| Animal parents protect their offspring in a variety of ways. Some conceal them in safe environments and others try to frighten off their adversaries. The giraffe never leaves the side of its young. The young roe deer (below) is concealed by its mother in the tall grass. She will not allow it to stand up tall. Above: Young owls are carefully looked after. |

Some other animals try to scare off predators to drive them away from their young. Owls and some other birds spread their wings wide open in order to appear larger than they really are, to frighten away predators approaching their young. Others will hiss like snakes. The blue tit hisses at a high pitch and beats its wings against the walls of its nest. Since the nest is totally dark inside, the aggressor can't determine what it's up against and usually withdraws quickly.86

Adult members of some bird colonies take it upon themselves to protect all of the young. For shellduck flocks, gulls are particularly dangerous. The shellduck adults on guard will show off their strength to drive the gulls away. Adult birds take turns protecting their young and, when they come off duty, will leave to feed in remote waters.87

When deer realize that they'll be unable to cope with an enemy, they'll throw themselves at the predator, offering themselves as prey and thus leading the predator away from their young. Many animal species use the same strategy. For instance, when the female tiger sees a hostile predator approaching, she immediately leaves her cubs and begins drawing the predator's attention. A raccoon, on the other hand, will take its young up the nearest tree, and quickly climb back down to face the enemy. It will let itself be chased for a long distance, and when it believes that it has led the predator far away enough, it quietly returns to its young. It goes without saying that not all these strategies are always completely successful. Even if the young survive, their parents may meet their deaths trying to protect the offspring.

|

| God inspires all living beings to care for their young and to be considerate and compassionate to them. |

Some birds pretend to be injured to draw predators' attention away from their offspring and onto themselves. Seeing a predator approach, a female bird quietly sneaks away from her nest. When she comes near the predator, she will beat the ground with one wing and cry out as if in pain. This makes her appear to have been injured and therefore, vulnerable. However, she's always careful to leave enough space between herself and the predator to let her escape. Her "performance" invariably attracts the predator's attention. It approaches in the expectation of an easy meal, not realizing it's being led away from the bird's nest. When it's safely out of reach, the female bird will stop pretending to be injured and, just as the predator reaches it, will fly off.

This theatrical show is very convincing indeed; it fools dogs, cats, snakes and even other birds. Many ground-nesting birds protect their offspring in this way. When a predator approaches, for instance, the mother duck pretends to be unable to fly, beating her wings wildly around the lake but always making sure she keeps a safe distance. Having led the intruder away sufficiently, she takes off and returns to her nest.

Scientists can in no way explain these birds' "injured wing" script.89 Could a bird really write such a scenario? It would have to be extremely clever to do this, since calculated pretense requires intelligence and skill. Also, the bird would have to be very brave to offer itself without hesitating and let the predator stalk it. No bird copies this behavior from other birds; this is an inborn defense mechanism.90

We have related here only a small fraction of the conscious, selfless acts of devotion found in the animal world. Millions of different species populate this Earth, each with its own defense mechanisms. More important than these systems is the lesson they teach us. Is it rational and logical to claim that a bird risks its life, consciously and by its own free will, in order to protect its young? Surely not. The animals we mentioned here are devoid of intelligence and cannot possibly possess feelings of compassion and mercy. It is God, Lord of the heavens and the Earth, Who creates them with these qualities, enabling them to act intelligently, compassionately and mercifully. By inspiring these animals, God reveals His own infinite compassion and mercy.

|

|

| In an act of great devotion, some birds pretend to be injured in order to draw attention away from their young, but endanger their own lives by this action. |

In 1764, the Swedish naturalist Adolph Modeer discovered that parent bugs protect their offspring and care for them. He observed that the female European shield bug, remains firm over its eggs when predators approach, protecting them against the enemy instead of flying away.91

At first, however, many scientists did not want to acknowledge that beetles cared for their next generation. Professor Douglas W. Tallamy, an evolutionist expert on insect behavior, explains the reason why:

Still, the ecological penalties for parental care can be so severe for insects that some entomologists wonder why it has persisted at all. The far easier strategy, followed by most insects, is simply to produce an abundance of eggs.92

|

| The lace bug, seen here protecting its nymphs from attacks by other insects |

Even though Tallamy believes in evolution, he is questioning one of the theory's dead ends. According to the theory of evolution, behavior that endangers a species' own lives should have been quickly phased out. But obviously, this did not happen! Many insects, like most other creatures in nature, never hesitate to risk their lives for their offspring and often—as in the case of wasps, bees, and ants— for one another.

| |

| Right: Brazilian Shield bug which lies on its nymphs to protect them from predators. 93 | |

One of the tiny creatures that does so is the lace bug that lives on horse-nettle plants. The female lace bug protects her eggs and later, her nymphs to the bitter end. One of the nymphs' worst enemies is the damsel bug—a beetle that, given the opportunity, will eat all the larvae with its sharp beak. But the female lace bug has no weapons to protect her young, and the only thing she can do is sit on the back of the enemy and beat her wings, trying to force it away.

| Larvae of the Brazilian tortoise beetle form a symmetrical ring under their mother's body. The mother begins guarding the eggs before they hatch, then leads its larvae to food sources. If one of the young strays or tries to escape, the mother will bring it back immediately.94 |  |

Meanwhile, the nymphs use the leaf's central vein like a speedway, escape via the stem and hide in some fresh uncurling new leaves. If the mother can manage escape with her life, she will follow the nymphs to whatever leaf they've hidden in and sit on the stem to guard them. In this way, should the enemy pursue, she cut offs the route leading to the nymphs. Sometimes, the mother chases her young for a short distance, to prevent them from going to an unsuitable leaf, and then leads them to a safer one instead. Mothers often die in these attacks, but they have bought time for their nymphs to escape and hide.95

For defenseless young to survive, their parents must feed and protect them. At all times, the adults need to be on guard against predators to protect their young, and must hunt for more food to feed them. Male and female birds feed their offspring between 4 and 12 times an hour throughout the day. If there are many chicks, they will fly hundreds of sorties to gather enough food for them. For instance, the great tit will deliver food to its nest up to 900 times a day.96

|

| Many animal species show their devotion when their young need to eat. For instance the great tit makes hundreds of flights every day to feed its young. The seal loses much weight when nursing its pups. |

Female mammals have an additional problem to deal with: They can feed their young only by suckling them. In this lactation period, they need to increase their food intake substantially. For instance, seals suckle their young for between 17 and 18 days after they give birth to them. The young gain much weight over this time, whereas the mothers will lose much, because they do not feed during this time.97

Parents that must care for their offspring use three to four times the energy they expend at other times.98

To determine the "cost" to parents of raising their young, biologist Heinz Richner and his students at the University of Lausanne made an experiment with the great tit—which revealed the difficulties of being a father. During this experiment, Richner frequently changed the number of young birds the father cared for by moving the fledglings around between nests. He found that father birds forced to feed an increased number of offspring worked twice as hard, and died sooner as a result. Parasites and illnesses associated with them affected 76% of these fathers, as opposed to an average of 36% under normal conditions.99

These results are important in helping to understand a bird's dedication for its young and the hardship it's prepared to suffer for them.

|

| The grebe feeds its young the feathers that will later aid in their digestion. |

The grebes serve as floating nests for their own young. Young grebes climb up on one of their parents. Once they have settled down, the adult bird raises its wings slightly to prevent the chicks falling off. It feeds its young by bending its beak back towards them and passing morsels through it, but their first meal is not food. First, the young birds are fed feathers collected from the water's surface or pulled from the parent's breast. Each little bird is made to swallow a considerable amount of feathers. But why?

These first feathers are fed to the young birds as a very important precautionary measure for their health. The young birds cannot digest these feathers, and so store them in their stomachs. Some of these feathers pack together like felt at the entrance to the intestine. Fish bones and other indigestible matter are caught there, preventing damage to the delicate lining of the stomach and intestinal walls. This habit of eating feathers will continue throughout the bird's life.100

In some species like the European kingfisher, the mother bird dives into the water at great speed and catches fish by the tail for her offspring. There is an important reason for her to catch them by their tails, because when caught like this, they can be fed to the young birds headfirst, so that the fins lie flat and do not stick in the young birds' gullets when they swallow the fish. If however the adult bird catches the fish just any which way, it will swallow the fish itself.101

|

| The guacharo bird. |

This species builds its nest at a height of 20 meters (65 feet). It will forage five or six times a night to gather fruit for its young. First it chews up the fruit, then feeds its young with the pulp.

The guacharo flies in flocks to search for food and covers an extraordinary distance of 25 kilometers (15 miles) a night.102

Like the guacharo, many other animal species will prepare food before feeding it to their young. Pelicans, for instance, prepare a sort of "fish soup." Shearwaters prepare a rich oil from the fish and plankton they ingest. In their crops, pigeons secrete a substance called "pigeon's milk" that is rich in fats and proteins. Unlike mammals, both male and female pigeons produce this "milk," and many other species of bird produce similar substances.103

Baby birds are totally dependent on their parents. They're able only to open their beaks wide and wait for the parents to feed them. Young herring gulls instinctively push their beaks towards a red spot on the mother's bill. At the slightest vibration that could indicate their parents' return, young thrushes, still blind, stretch their necks upwards and open their beaks wide in anticipation, as if the swollen yellow rims of these young birds' beaks were indicating where their parents should deposit their food. The edges of their gapes are quite sensitive. If a baby has its beak closed for whatever reason, the slightest touch will stimulate it to open its beak.

|

| Many species like the pelican prepare food for their offspring in their crops. As seen here, a young pelican eats food from its mother's crop on her return. |

The color and sensitivity of young birds' mouths, especially in birds whose nests are located in deep down places, make life easier all around. A mother can easily find the gapes of her young, even when they're sitting in a dark corner of the nest.

Gouldian finches build their nest in a dark hole in the ground. Their young have brightly colored green and blue knobs at the corners of their gapes, which act as reflectors for the little light that filters through into the deeper corners of the nest.

In some species of birds, colorful gapes serve purposes other than just indicating the location of the young. They can also indicate which of the young has recently been fed, and which are still in need of feeding. The gapes of young linnets are ruddy because of the blood vessels located just under the skin of the throat. After the young have been fed, their blood is drawn to their stomach in order to digest the food. Therefore, those birds that have gone without food the longest will have the reddest gape. Experiments conducted in this area have revealed that parent birds utilize these color differences when determining which of their youngsters to feed.104

The way bird behavior harmonizes with their environment is clear proof that creatures, and all of the natural world they live in, are the handiwork of one Creator. No string of coincidences can possibly produce such perfect harmony.

| "There is no creature on the earth which is not dependent upon God for its provision. |

|

In nature, all animals' features are in accord with their environments. An excellent example of this is sandgrouse, which has no specific place of abode in the vast desert. When they need to lay eggs, they find a shallow hole in the sand and lay three eggs at most. As soon as the chicks hatch, they leave the nest and begin roaming for seeds, which they can find for themselves. But because they cannot fly yet, they are unable to reach water to still their thirst. Therefore, water needs to be brought to them—and the male sandgrouse caters to this need.

|

| Above: Sandgrouse drink first, then wet their feathers to transport water for their chicks. Below. |

|

| The mother stork carries water in her crop to cool her young. |

Some other species of bird transport water for their young in their crops. But because the male sandgrouse must bring water from so far away, the quantity he can store in his crop covers only his own needs during this long journey. But he has a unique feature for this purpose. The inner surface of the feathers on his breast and underside are covered with very fine filaments. When the bird reaches a waterhole, he rubs his underside against sand or dust, thus removing any preen oil that might prevent the absorption of water. After drinking as much water as he can for his own needs, he then enters the water, raises his wings and tail, and wriggles about. This soaks all the feathers on his belly, and the filaments lining his feathers absorb the water like a sponge.

The water he transports between his body and feathers is protected against evaporation, but some still does evaporate if he must cover a distance of greater than 30 kilometers (20 miles). When he finally reaches his chicks, who are roaming for seeds, they run up to him straight away. When the male sandgrouse lifts his body, the young can drink the water like mammals drinking milk from their mother's body. Once they have drunk all the water, he dries himself by rubbing his body against the sand. The male sandgrouse continues to repeat this every day until the chicks are about two months old and molt for the first time, after which time they can get their own water.107

|

| Bee-eaters feed their young with bees, insects, wasps, butterflies, mantids and termites. In order to prevent injury to their offspring, first they smash the victims against a branch to kill them. 105 Right: Young bee-eaters awaiting feeding. Left: The bee-eater delivering food to its young. |

|

| Parent birds are among the most hard-working of animals. They fly countless times, sometimes as many as a thousand times a day, in order to find food for their chicks. 106 |

|

We need to reflect on a number of aspects in sandgrouse's behavior. Besides endowing it with the exact features it needs to survive in this environment, He also inspires it to know exactly what it needs to do.

| ||

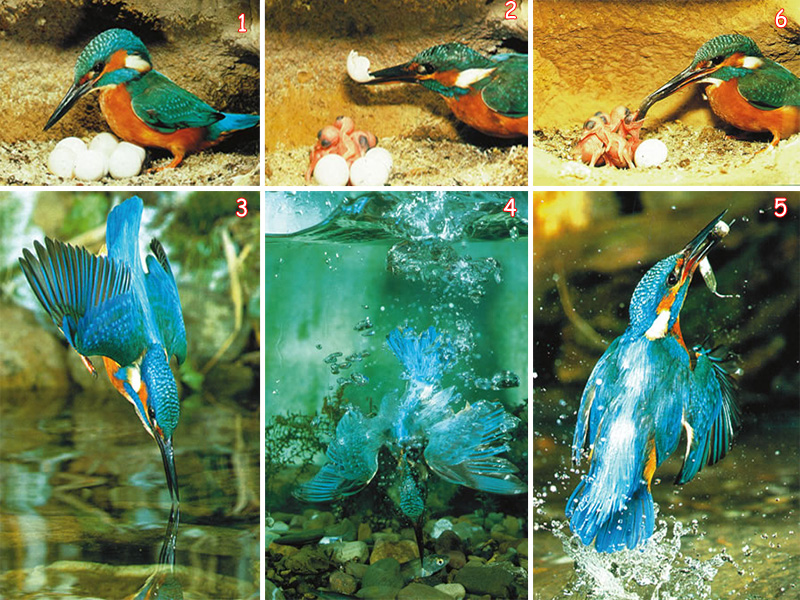

| Parent birds spend most of their time hunting for food. God provides for each of them in a different way. Here, the kingfisher, after helping its young emerge from their eggs, dives for fish. | ||

| 1- The kingfisher with its eggs. | 3. Diving for fish. | 5. Taking prey home to its young. |

Many insect species feed their larvae and offspring. Burrowing bugs, for example, feed their larvae, concealed in a burrow, with seeds. Treehoppers open up spiral slits in the bark of trees, exposing the tiny tubes that carry nourishing sap from which their tiny larvae feed. Wood eaters have a hard life. They must somehow convert wood, which is not only difficult to digest but contains only little nitrogen, into an edible form for their larvae. Wood roaches and passalid bess beetles that feed on wood have solved this problem by feeding their nymphs with softened wood fibers and single-cell organisms that can break down cellulose, along with intestinal fluids rich in nitrogen. Bark beetles chew the wood and lay their eggs in the tunnels they open up. On the wood, they place fungus that will break down the cellulose into a substance their larvae can eat.108

God sustains every species in a different way. The insects mentioned find their sustenance in the way God wills. He makes their parents provide for these tiny creatures and in the Qur'an, He reveals that it is He Who sustains every living thing:

How many creatures do not carry their provision with them! God provides for them and He will for you. He is the All-Hearing, the All-Knowing. (Qur'an, 29: 60)

| "God is the Creator of everything and He is Guardian over everything." |

|

Newborn animals, generally weak and clumsy, need their parents to carry them away in case of danger or if they need to be moved elsewhere. Each species has a different method of transporting its young. Some carry them on their backs, others in their mouths and still others in special pouches under their wings. While being transported, the young are not harmed in any way and are quickly taken to a safe environment.

Transporting the young out of harm's way is an important example of parental devotion, because carrying the young considerably reduces the parent animals' speed and mobility. Despite this, animals never desert their young in the face of danger.

How Do They Carry Their Offspring? |

|

| Many species of animal remove their young from danger, and each species has its own way of doing so. Lions hold their cubs by their necks without injuring them. In case of danger, the young kangaroo jumps headfirst into its mother's pouch. Frogs, ducks, scorpions, bears and monkeys all carry their young on their backs. |

|

|

| Koalas carry their young for over a year before they are ready to protect themselves. 190 |

|

| Monkeys can jump from tree to tree with their young on their backs. |

|

| For young bears, their mother's back is both safe and comfortable. |

|

Most commonly, animals transport their young on their backs. Monkeys, for example, can carry their young everywhere they go. The mother can move around unhindered with her baby because it grips the mother's back or belly fur with its hands and feet. With her baby on her back, the mother can easily climb up a tree, run along a branch, and jump to the next tree.

Kangaroos and other marsupials carry their dependent young on their bellies in fur-lined pouches. For its first five months, a baby kangaroo lives in its mother's pouch. When it leaves the pouch, it will not stray far for the first few days. If it senses danger, it will run back to its mother and jump into the pouch headfirst, whereupon the mother departs rapidly on her strong hind legs.

Mother squirrels will grip their youngsters' droopy bellies in their teeth. If a mother squirrel's nest is disturbed, she will carry her young as far away as need be, taking them one at a time and returning back to the old nest until all of them have been removed to safety.

Baby mice hold on tightly to the mother's nipples for hours on end without letting go. In case of danger, the mother can drag her offspring quickly away. The young have such a good grip on her that she can run away without pausing to gather her infants together and placing them securely between her legs. When danger has passed, she will return to the old nest, just in case she might have left one behind.

When bats are roaming for insects or fruit, they will carry their young with them throughout the night. A baby bat grips the nipple with its milk teeth and holds on to its mother's fur with its claws. Some bats can still fly with three or four young all holding onto their body.

Many species of birds will fly with their young. If a woodcock's nest is endangered, the mother can quickly take off with her chick between her legs. Rails, marsh hawks, and chickadees fly their young to safety by carrying them in their beaks. Red-tailed hawks grip their young in their talons, just as when they carry prey.

Grebes carry their young on their backs. If they spot danger, they dive under water with their young still clinging on.

Tropical frogs can hop to safety while carrying their eggs or tadpoles on their backs.

More interestingly, some fish carry their young to safety in their mouths. A male stickleback guards and protects its offspring by swimming around its nest made of water weeds. If one of the young strays, the male fish will follow, suck it in into his mouth and release it back at the nest.

Ants carry larvae and developing eggs in their jaws from one nursery chamber to another. Every morning, worker ants carry the colony's larvae to a chamber near the top of the anthill, where it's warmed by the sun. As the sun moves across the sky, the larvae are transported from one side of the nest to the other. Come evening, the workers carry them back down to a chamber at the bottom of the anthill which has retained the sunlight's heat. At night, the entrance to the nursery chambers is closed off in order to keep out cold air. In the morning, the entrances are opened again, and the larvae are carried back up.110

As we see, all living things from lions to insects, frogs to birds, carry their offspring to safety. For the parents, this is always hard work and often endangers their own lives. How can such a strong protective impulse be explained? We've examined in detail how many creatures take on the responsibility of rearing offspring until they can fend for themselves. They cater without fail to all their offspring's needs, and it is possible to see examples of this devotional behavior in a wide variety of beings.

Once again, the obvious truth confronts us: Each of these creatures is under the protection of God, Who inspires their behavior. All act accordingly, bowing to His will. The Qur'an reveals this truth in the following way:

Everyone in the heavens and earth belongs to Him. All are submissive to Him. (Qur'an, 30: 26)

67.Amanda Vincent, "The Improbable Seahorse", National Geographic, October 1994, pp. 126-140.

68.Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom, C.B.P.C. Publishing Ltd. (London: Phoebus Publishing Company, 1976), p. 92.

69.Ibid., p. 33.

70.Ibid., p. 37.

71.Jacques Cousteau, The Ocean World of Jacques Cousteau, Quest for Food (New York: World Publishing, 1973), p. 32.

72.Ibid., p. 35.

73."A colorful Jewel from Southern Mexico, 'Cichlasoma' salvini," www.cichlidae.com/articles/a109.html.

74.Amanda Vincent, "The Improbable Seahorse", National Geographic, October 1994, pp. 126-140.

75.Ibid., p. 26.

76."Ostrich," San Diego Zoo, www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-ostrich.html.

77.Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom, pp. 246-247.

78.Douglas W. Tallamy, "Child Care among the Insects," Scientific American, January 1999, Vol. 280, no. 1, p. 55.

79.Ibid., pp. 53-54.

80.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, pp. 43-45.

81.Slater, The Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, p. 88.

82.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, p. 1.

83.Ibid., p. 56-58.

84.Ibid., p. 36.

85.Ibid., pp. 47-48.

86.Ibid., p. 5049.

87.Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 2598.

88.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, p. 501.

89.Ibid., p. 53.

90.Ibid., p. 52.

91.Douglas W. Tallamy, "Child Care among the Insects", Scientific American, January 1999, Vol. 280, no. 1, p. 52.

92.Ibid., pp. 52-53.

93.Ibid., p. 53.

94.Ibid., p. 52.

95.Ibid., pp. 51-52.

96.Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 270.

97.Slater, The Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, p. 86.

98.Bellani,Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid,p. 22.

99.Bilim ve Teknik (Science and Technology), April 1998, no. 365, p. 12; and Science et Vie, no. 967, April 1998.

100. Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 256.

101. Bellani, Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid, p. 100.

102.Ibid., pp. 123-124.

103.Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 262.

104.Ibid., p. 263.

105.Bellani, Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid, p. 95.

106.Seddon, Animal Parenting, p. 32.

107.Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 279.

108.Tallamy, Scientific American, January 1999, p. 53.

109.Seddon, Animal Parenting, p. 34.

110.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, pp. 36-42