|

Some animals remain with other family members for a very long time, or even for life. Penguins and swans, for instance, are birds that mate for life. Female elephants stay together with their mothers and even their grandmothers.25

In mammals, usually the males establish families consisting of females and their young. But leading a family brings with it many responsibilities. The male must hunt for food more often, as compared to a single male. He can easily protect himself, but must take care for and protect the other family members as well. Guarding the defenseless young often requires selfless behavior.

This is an important matter that should be reflected on: Animals make great efforts to establish their families, to care and provide for them. To do so, they risk their own lives and forsake an easy life for themselves. Why should animals choose these harder options?

This tendency completely disproves Darwin's "the fittest survive and the weaker perish" thesis. As the many examples over the following pages will demonstrate to the contrary, the weak are often protected by the strong, who thereby endanger their own lives.

One prerequisite for social life is that family members can immediately recognize each other. Even in wide open spaces where animals live side by side in large colonies, they can recognize their own offspring, mates, parents, and siblings.

Each species has a different method of recognizing its own. Ground-nesting birds recognize their young's voices as well as their looks. One example of this are Herring gulls, which raise their young in huge colonies. Even when their chicks are out of sight, parents recognize and respond to their calls without ever confusing their calls with other young gulls'. If a stray young bird trespasses their nesting spot, they recognize and chase away the intruder.26

Usually mammals recognize their own young by their smell and taste. As soon as a baby is born, the mother sniffs and licks it and from then on, never confuses it with any other.27

Among the most successful creatures in this respect are penguins. They look so alike that when humans observe them carefully, it's almost impossible to tell them apart. Thus it is so astonishing that the members of a penguin family can recognize one another with no difficulty. Consider that the mother leaves her mate and young for a period of two to three months in order to search for food. Yet on her return, she recognizes them both.

|

| Penguins leave their young together when they go off hunting. The young huddle together to keep themselves warm. But how do the parents recognize their young on their return? God has created the penguins with the ability to recognize one another by voice, letting penguins easily recognize their identical-looking mates and young. |

|

Among the hundreds of other penguins, the mother penguin easily finds her own mate and their chick. More interestingly, before the adult females set off to go hunting in the sea, they gather all the young to form a nursery as a precaution against the freezing cold. The young birds stay closely packed together, taking advantage of one another's body heat. But there is one problem: How are the adult birds going to recognize their own young on their return from their hunting trip from among the hundreds of other birds. This though does not seem to pose a problem for penguins. Each adult begins to call at high pitch and the young birds recognize their parents by their sound and move towards them. 28

No doubt, recognition by voice is under these circumstances the most appropriate method for the thousands of penguins. But, how come penguins have the very same appearance but distinct voices so they can recognize one another? Furthermore, how did they acquire the skill to distinguish each other by voice? No penguin could have come up with the idea of such qualities and skills and then adopt them by themselves. These must be given qualities, but by whom? According to evolutionists, it is nature—but what part or feature of it could provide animals with such abilities? The ice on the poles, maybe? Perhaps the rocks? Obviously neither, because "nature," to which evolutionists ascribe this and many other powers consists of rocks, stones, trees, ice and the like, which are a totality of created matter. Therefore, the answer to the above question is simple: God creates everything perfect within itself, gives each penguin a distinct voice note and the ability to recognize by voice, thereby making their lives easier for them.

Nests play an important role in protecting animals, in particular their young. Many species use a wealth of astonishing techniques to construct nest with a variety of diverse architectural details. Animals plan often like architects, working like master builders, finding technical solutions like engineers, and sometimes adorning their nests like decorators. Often they work tirelessly, day and night, in constructing their nest. Their mates often share the workload, and the two assist each another. The nests most carefully prepared are those built for the expected arrival of the young.

|

| Many mammal species clean their newborn young by licking them, during which process they also memorize its smell. Thereafter, they can easily tell their young apart among all other young of the same species. |

The various techniques used to build these nests are so perfect that one would not expect them from animals devoid of intellect and technological skills. As the following pages will show in great detail, they could not have been designed by the animals themselves, because they would have to plan out the many stages of the project before even beginning to build. First off, they'd have to realize the need for a nest for the safety of their eggs and young. Next, they'd need to locate the most suitable place for their nests, since no creature builds its nest just anywhere.

Building materials used in the nest's construction are carefully selected from those available in the environment. For example, water birds build nests from plant matter that will float, in case of unexpected flooding. Birds living among reeds, on the other hand, make their nests wide and deep, to prevent their eggs from falling out when the reeds bend in the wind. Birds inhabiting deserts build their nests atop of shrubs and cacti, where the temperature is 10o C (50o F) lower than on ground level, where the oven-like 45o C (113o F) heat would kill the young birds in a very short time.

|

| Penduline tits build bottle-shaped nests, putting in a lot of effort and using a variety of materials to build the nest, which hangs from a branch. |

Choosing the right location for a nest requires knowledge as well as intelligence. An animal cannot foresee the risks of flooding, or the danger that high temperatures pose for young birds—much less how to prevent their adverse effects. We are faced, then, with a paradox: On the one hand, animals of little intelligence and no knowledge and, on the other, behavior that is conscious, intelligent and knowledgeable. God is the owner of consciousness, intelligence, and knowledge; and expresses these qualities in His perfect creations.

The healthy survival of their offspring is vitally important for all living species; and from the moment of laying their eggs or giving birth to their young, protecting them becomes the parents' sole occupation. The penduline tit, paying utmost attention to the safety of its offspring, builds a number of dummy nests in the vicinity of its real nest, to divert the attention of any hungry enemy. This diversion strategy, obviously the result of careful planning, couldn't possibly be the product of the penduline tit's own intellect.

One of the most common methods birds use to protect a nest from predators is to build it in a thorny bush or camouflage it among dry leaves. Some species, in order to protect the female and her eggs, wall off the entrance to their nest structure with mud while she is inside, or else mix their saliva with soil to form a sort of mortar they use to build a wall covering the entrance.

These can hardly be skills those animals could develop on their own. What, then, enables these birds and other animals to build nests so intricate and perfectly designed? How do animals acquire these skills?

Another detail should not be disregarded. At birth, every animal possesses the knowledge of building its characteristic nest. Every member of that species, wherever on Earth it might be, builds its nest in the same way. This clearly shows that creatures did not learn their nest-building methods or acquire them in any casual sort of way, but that this knowledge and skill was given them by the same power. God, the All-knowing and All-powerful, creates them together with their skills and gives them this knowledge.

Quite aside from their architectural perfection, the extraordinary dedication that parents invest in building their nests is certainly worth noticing. Whereas birds build ordinary nests for themselves, they build ones for their offspring with the utmost care. Considering the different phases involved in nest building, we can better understand the scale of the efforts birds put into it, the energy they invest and the selflessness of their behavior. To build its nest, a bird can carry only a few twigs or grass stalks at a time in its beak, and so must make hundreds of flights to gather the building materials it requires. But this does not discourage the bird. It continues to forage patiently. It never becomes frustrated, never settles for less, is never too tired or lazy to complete its nest in every last detail.

| "God created you from dust and then from a drop of sperm and then made you into pairs. No female becomes pregnant or gives birth except with His knowledge. And no living thing lives long or has its life cut short without that being in a Book. That is easy for God." |

|

According to Darwin's natural selection theory, these animals should be concerned only with themselves. In an environment where only the fittest and strongest could succeed in the battle for survival, would animals exhaust themselves so that their vulnerable offspring could survive? What could explain their preparing in advance a secure environment for the arrival of their vulnerable young? Natural selection cannot answer these questions; neither can the theory of evolution, nor any other atheist ideology. These questions have one answer only: God gives to these animals dedication, patience, endurance, persistence and ambition. God instills them with these qualities so that the strong can protect the weak, so that natural balances can continue and these species can exist until their appointed times and can become living signs of God's artistry, power, wisdom and the superiority of His creation.

Subsequent pages will give examples of animals renowned for their architectural and decorative skills. Eggs and later on, the young birds that hatch from them are vulnerable in the extreme, and especially in need of protection. Therefore, God directs their parents to build them exactly the right type of nests.

Birds are the ultimate nest-builders. Each different species has its own unique nest-building techniques and constructs these structures without ever getting confused.

When the parent birds leave the nest to search for food, their offspring are completely defenseless. Their nests that are concealed with great skill in treetops, holes in trees and cliffs, or even amidst tall grass, provide a safe, hidden shelter for the chicks.

Another purpose of the nests is to provide protection from the cold. Birds are hatched featherless, and since their muscles do not get exercised within the egg, they are relatively immobile and thus need nests to insulate them from the cold. Woven nests in particular trap body heat, providing warmth for the chicks—but constructing these structures is a detailed and difficult undertaking. The female builds the nest by carefully weaving grasses, twigs, and scavenged yarn over a fairly long period of time. She cushions the inside with feathers, hair and fine grass, thereby further insulating the nest.29

|

| The thornbill's nest lies between two leaves. Like tailor birds, they use their beaks as needles and spider silk as yarn. Tailor birds skillfully stitch leaves together, using their beaks as needles, and plant fibers or spider silk as yarn to make cozy nests. |

For every type of nest, finding the right building materials is essential. Birds can spend a whole day in their quest for the building materials their structure needs. Their beaks and talons are designed for carrying and arranging the materials they gather. The male bird chooses the location of the nest, and the female builds it.

These nests' features depend on the materials and techniques used in their construction. All building materials for their architectural masterworks must be pliable and compressible. Nests are built taking into account the elasticity, durability and toughness of the different materials birds use—mud, leaves, feathers, cellulose and the like. This increases the structure's durability. Using plant fibers mixed with mud, for instance, prevents cracks from developing.

First, birds mix the mortar from the materials they gather. One species that uses this technique is the cliff swallow, which builds its nests on cliffs and the walls of buildings, using mud as an adhesive to glue their nests together. They gather mud and feathers and transport them in their beaks to the construction site, where they mix mud with their saliva, smearing the mixture against the face of the cliff to form a pot-shaped structure with a round opening on top. This structure they fill with grass, moss, and feathers. Usually they build these structures in cavities under overhanging cliffs, to prevent rain from softening and thus destroying the nest.30

Some South African birds like the penduline-tit build nests comprised of two compartments. The real entrance to the brooding chamber is concealed, while the other entrance is readily visible, presenting a false doorway to any predators.31

The oropendola, a large and quite distinctive bird, builds its nest next to the those of wasps, which automatically keep snakes, monkeys, toucans and botflies (a type of fly deadly for these birds), from approaching their nests.32 In this way, the oropendola protects its young from the dangers that all these creatures pose for their young.

The tailor bird of India has a beak like a sewing needle. As thread, it uses silk from cobwebs, cotton from seeds, and fibers of tree bark. This bird selects two or more large green leaves growing close together at the end of a branch and pulls them together. It then punches holes along the edges of each leaf, and pulls the spider silk or plant fiber through the holes to sew the leaves together, finally tying knots in each stitch to keep it from slipping. It does the same on the other side, stitching the leaves together, taking approximately six stitches to curve a leaf around. Eventually the bird fills this resulting purse with grass.33 Finally, it weaves another nest into the purse, where the female will lay her eggs.34

Naturalists consider these birds' nests to be the most astonishing structures built by birds. This species uses plant fibers and tall plant stems to weave themselves extremely solid nests.

First of all, a weaver bird collects the building materials. It will cut long strips from leaves or extract the midrib from a fresh green leaf. There is a reason for its choice of fresh leaves: The veins of dry leaves would be stiff and brittle, too difficult to bend, but fresh ones make the work much easier. The weaver bird begins by tying the leaf fibers around the twig of a tree. With its foot, it holds down one end of the strip against the twig while taking the other end in its beak. To prevent the fibers from falling away, it ties them together with knots. Slowly it forms a circular shape that will become the entrance to the nest. Then it uses its beak to weave the other fibers together. During the weaving process, it must calculate the required tension, because if it's too weak, the nest will collapse. Also it needs to be able to visualize the finished structure, since while building the walls, it must determine where the structure needs to be widened.35

Once it finishes weaving the entrance, it proceeds to weave the walls. To do so, it hangs upside down and keeps on working from the inside of the structure. It will push one fiber under another and pull it along with its beak, until it accomplishes a stunning weaving project.36

The weaver bird won't just begin building its nest. It proceeds by calculating in advance what it needs to do next—first, collecting the most suitable building materials, then forming the entrance before going on to build the walls. It knows perfectly well where to thin or thicken the structure, and where to form a curve. Its behavior displays intelligence and skill, with no trace of inexperience. With no training, it can do two things at once—holding down one end of the fiber with its feet, while guiding the other end with its beak. None of its movements is coincidental; its every action is conscious and purposeful.

Another member of the weaver bird family builds a solid, rainproof nest. This bird obtains the perfect mortar by gathering plant fibers from the environment and mixing them with its saliva, which gives the plant fibers both elasticity and makes them waterproof.

|

| Inspired by God, weaver birds build themselves spectacular nests. Above and Right: The stages of nest building. First, the bird tears off thin strips of leaf. Then it begins to build the nest by pressing the end of the strip onto the branch with one foot, while weaving the other end with its beak. As these pictures show, it uses its beak as a shuttle, threading a single plant fiber alternately over and under other strips. Left: A weaver bird finishing its nest. |

|

| Some weaver birds live in colonies, building themselves nests to shade them from the scorching heat of the sun. |

Weaver birds repeat this process until their nest is complete. It's no doubt impossible to claim that they have acquired these skills unconsciously, by chance. These birds construct their nests like an architect, construction engineer, and site foreman all rolled into one.

Another interesting example of nest building is performed by sociable weaver birds of southern Africa, which nest in a single huge, cooperatively built structure with separate entrances. With the ingenuity of accomplished architects, sociable weavers build these nests, some of which are home to as many as 600 birds.37

When it comes to nest building, why does this species choose the more complex over the easier option? Can we possibly ascribe to chance the fact that they can build such complex nest structures all by themselves? Surely not—like all other creatures in nature, they too act by the directives of God.

Some birds hide their nests underground. Bank swallows, for instance, dig long tunnels in the sides of steep slopes along rivers and shorelines. They slant their tunnels at an upwards angle to prevent them being flooded with rainwater; and at the end of each tunnel is a grass- and feather-lined nesting chamber.38

The cloud swifts of South America build their nests behind waterfalls, even though it is almost impossible for birds to penetrate waterfalls. Hawks, herons, gulls or crows cannot manage to break through the fast-falling water. One would expect any bird attempting this feat to be crushed in mid-air under the tons of water. But these swifts are very small and fly fast enough that they can shoot through the waterfall like arrows. Their chosen nesting sites are safe, because no other animal dares try to reach them there.

|

| The cloud swifts build their nests behind waterfalls, on rocks that no other animal can reach. |

However, these swifts do have problem in gathering building materials for their nests. Their feet are too small to let them pick up materials from the ground, as other birds do. So instead, they catch feathers, fragments of dried grass and such materials that float in the air. Then they stick them to the cliffs behind the waterfalls with spittle from their salivary glands.39

Cave swiftlets inhabiting the shores of the Indian Ocean build their nests in caves. Each wave breaking against the shore completely floods the entrance to the cave. That is why these birds can sometimes be seen hovering above the waves outside a cave, waiting for the foaming water to recede, so that they can dart into the cave. Before they begin to build their nests, swiftlets determine the highest water level by observing the marks that water leaves on the walls around the cave entrance, and then build their nests above that.40

The long-legged secretary bird of Africa builds its nest in prickly thorn trees to protect it from predators. Woodpeckers in the American Southwest drill nesting holes in the stems of giant cactus plants;41 while the marsh wrens, on the other hand, prepares dummy nests. While the female is building the real nest for their young, the male wren flies around the marsh, building the decoy nests that will draw predators' attention away from their real one.42

Almost every species of bird is greatly dedicated to its young. To mate, albatrosses always return to their place of birth, where they form huge colonies. Weeks before the females arrive, the males restore last season's old nests to provide a comfortable abode for the coming young. Albatrosses' dedication to their eggs is remarkable, inasmuch as they sit for 50 days without getting up.

Nor is their dedication limited to protecting and caring for their eggs. Often they fly distances of over 1,500 km—a thousand miles—to gather food for their chicks.43

|

| Albatrosses build protective nests for their young. Weeks before the female birds arrive on the nesting site, the males come to restore and repair the old nests. |

|

| The male hornbill walls up his mate and eggs in a hole in a tree and looks after them there. |

For the hornbill, the mating season heralds the beginning of great activity. During this period, both males and females make an outstanding performance. The first thing they need to do is build a safe nest for the female and their offspring.

The female hornbill starts work by finding a suitable hole in a tree that will shelter the nest. She narrows the opening on the tree by plastering it with pellets of mud she carries in her beak. After entering the nest through the narrowed hole, she seals the entrance with mud that has dropped inside, thus reducing the gap to a beak-size slit. This will protect the female and their offspring from external dangers, particularly from snakes. After the nest is finalized, the female sits for three months without once leaving the nest. The male gathers food and feeds his mate through this small opening. When the young hatch, they too are fed by the same way.44 Both birds are very patient and dedicated to their offspring. While the female bird sits in this tree hole barely big enough for herself, for three month without ever leaving, and the male never deserts them in all this time.

From these examples, we have seen that each species of bird has its own way of constructing nests. Each technique requires a design planned in advance, and is of such a complexity that couldn't be expected from creatures without intellect or the faculty of forethought.

| And there is certainly a lesson for you in your livestock... |

|

| Each species of bird makes its own distinctive type of nest. Flamingo nests are as pleasing to look at as the birds themselves. |

We're faced with organisms devoid of reason and the willpower necessary to behave with compassion, mercy and devotion. However, these creatures clearly demonstrate the products of intelligence, reason, planning and design and compassionate and altruistic behavior. So what is the source of their behaviors? If they lack the capacity to produce these actions through their own willpower, there must be a power that teaches them to act in this way. This power is God, the Lord of the earth, the heavens and everything in between.

| |

| The bare-headed bird is seen sitting on the rock nest made of mud. | Swift bird built a nest to protect her cubs. |

|

| The devoted bumblebees |

Bumblebees display quite interesting dedication. The young queen, just before it's time to lay her eggs, starts seeking out a suitable place to start her own colony. Once she determines the location, she begins gathering the building materials she needs to upholster her hive—feathers, leaves, and grass—and also as insulation material.

First, with material collected in the vicinity, she builds in the center of the nest a small chamber the size of a tennis ball. Then it's time to gather food. On leaving, she flies in circles in the air above her nest, facing it at all times, so as to memorize its location. After collecting nectar and pollen for food, she returns and deposits her loads into the center of the chamber.

The queen feeds on nectar and, after a certain time, begins to secrete beeswax. She doesn't discard the portion of nectar that she cannot consume, but lets it dry and uses it to bond together the building materials she's collected to construct the chamber. She fills the cells she has made with nectar for food, and places a tiny lump of pollen in the bottom of the other cells and lays white eggs on top, which will hatch into the first worker bees. The cells are sealed with more wax and the queen bee keeps them warm until they hatch.

She does not lay her new eggs randomly, but places them symmetrically and with utmost care. However, equally important as the hatching of the eggs is feeding the young. Their food is ready in the cells filled by nectar by the queen bee. After an incubation period of from four to five days, the larvae hatch and begin to feed on the pollen and nectar readied for them.

It is noteworthy that the creature that distributes nectar where the young can reach it and builds a system that will ensure healthy growth for the young bees that will form the colony is not a being of intelligence, but a little bee only a few centimeters in size.

Why is the queen bee so devoted? That's the first question that jumps to mind. She'll derive no benefit from the young she feeds, especially since on the arrival of a new queen, she can be forced to leave the colony for which she worked so hard and sacrificed so much. There can be only one reason for the bumblebee to show such selfless devotion and put so much effort into raising new generations: Like all other creatures on Earth, the queen shows all this devotion because God directs her to be devoted and raise new generations. This means that the creatures of nature are not possessed by a selfish survival instinct as the evolutionists claim.45

When they are pregnant or have cubs, female polar bears living in the freezing cold of the Arctic build themselves dens under the snow and ice. Otherwise, they do not live in dens. Cubs are usually born in midwinter—tiny, blind and naked. In the winter cold, a den is essential for these dependent, defenseless cubs to survive.

A typical polar bear's den is a tunnel usually about two meters (6.5 feet) by 1.5 meters (5 feet) in size, and approximately one meter (3 feet) in height. This common abode is not simply dug out. In an environment entirely covered in ice and snow, it comprises essential details necessary for the cubs' survival.

Usually these dens have more than one room, which are built higher than the entrance. In this way, body heat from the chamber cannot escape through the den's entrance. Throughout the winter, snow piles onto the entrance and atop the den itself. In this great heap of snow, the polar bear leaves an opening just big enough for ventilation.46

|

The mother polar bear makes the den's roof between 75 cm (2.5 feet) and 2 m (6.6 feet) thick, which insulates the den quite well, keeping in the heat and fixing the air at a constant temperature.47 In this lukewarm, protected environment, the mother bear stores energy and adjusts her fat reserves according to her period of hibernation.

Researcher Paul Watts from Norway's Oslo University placed a thermometer in the upper wall of one den. Monitoring the temperature, he made an interesting discovery. While the outside temperature measured below -30 C (-22 F) degrees, the internal temperature never fell below 2 to3 degrees. How does the mother bear know that the roof's insulation property changes according to its thickness? This has been the subject of scientific curiosity.

This poses another, even more interesting issue. During her hibernation, the mother bear reduces her metabolism rate, so as not to use up any energy and to provide more milk for her cubs. For seven months, she converts her stores of fat into protein. Because of this, she does not eat for all that time, reducing her pulse rate from 70 to 8 and slowing down her metabolism. Neither, during this period, does she have to relieve herself. During the period when she will give birth, she won't have used up much energy.

|

| The nest built by the female crocodile for her eggs. |

In Florida's Everglades, the female crocodile builds a very unusual nest for her eggs. First, she mixes decomposing plant matter with mud and builds a mound approximately 90cm (35 inches) high. She makes a little hole at the top, in which she lays a few dozen eggs, then covers them all with some more vegetable matter. From then on, she guards the mound against predators. As the eggs begin to hatch, she hears the noises the baby crocodiles make and removes the covering of decaying vegetation. The young quickly clamber to the top of the mound, where the mother crocodile takes them into her mouth and carries them to the water inside it.48

Among amphibian parents, one of the best nest builders is South African smith frog. The male builds a nest by the edge of the water, going around in circles until it has made a hole in the mud, then pushes against the hole's walls to widen it. Once its work is finished, it will have built a pool 10cm (4 inches) deep, with solid mud walls.

Sitting in this pool, the smith frog makes its mating call until it attracts the attention of a female frog. Responding to his call, she lays her eggs in his pool. After the male fertilizes the eggs, both frogs guard them until they hatch. When the tadpoles emerge, they swim about in this enclosure, safe from fishes and insects. After they grow large enough and develop legs, they climb the walls and leave this carefully prepared nursery.49

It is not widely known that fish build nests, but a surprising number of freshwater species do—in ponds, lakes and streams. Usually they clear shallow depressions in the sand or gravel bottom. Once they have laid their eggs, salmon and trout close up the nests and then leave the eggs to hatch. In species that leave their eggs exposed in an open nest, one or both parents guard them. In many species, only the male fish builds the nest and guards the fertilized eggs.

The nests of some other species are more complex. Male sticklebacks, found in rivers and ponds in North America and Europe, build nests even more sophisticated than those of most bird species. The stickleback collects plant material and secretes a substance produced in its kidneys to bond it together. It swims along and around this material to give it an oblong shape, then finally forces its way through the middle, to form a tunnel through which water can circulate. If a female approaches the nest, the male performs his courting display by darting around to left and right. He leads the female to his tunnel nest and indicates its entrance by pointing with his head. When the female finishes laying her eggs inside the tunnel, the male enters through the front, fertilizes the eggs and finally, pushes the female out the back. After several females have filled the tunnel with eggs, the male guards the nest and makes sure fresh water keeps on circulating through the tunnel. Repairing and maintaining the nest as needed, he will keep on guarding the nest for a few more days after the eggs have hatched. Then he removes the nest's top half, leaving the rest as a nursery for the baby fish to use.50

|

| It's not widely known that fish build nests. Many freshwater fish species build nests for their eggs and young, and also guard their eggs until they hatch. Above: A nest made of gravel and seashells, and the larvae inside the nest. |

Consider whether it's possible for someone who's never worked on a building site before, without anyone to explain materials or how to use them and with no plan to fall back on, to build himself a perfect residence. Surely not! It's hardly reasonable to expect this feat of an intelligent human being, never mind a fish.

If this behavior of intelligence and skill cannot be expected of a human, how can we expect it in an animal? They work patiently and with much dedication in building their nests; and often only their young live in them. Many of the species given as examples in the preceding pages don't even have a very complex nervous system, much less a highly developed brain. When they build their nests, however, they plan and calculate, apply the laws of physics, use weaving and stitching techniques requiring skill, along with satisfying their own needs as well as their offspring's in a practical way. They mix mortar and insulate their nests with easily obtained materials. But how can a polar bear or bird know how insulation works? Or deduce that it needs to retain the heat in its nest? It's self-evident that none of these qualities originates in the animal itself. So how do creatures come by this inborn knowledge?

These animals' intelligent behavior, knowledge and dedication have only one source: All these are God-given qualities. God has created these creatures to be hard working and dedicated, providing them with the abilities to hunt, feed, breed, and protect themselves so that they can continue their species. In His infinite compassion and mercy, God makes them build their nests; enables them to make perfect plans; protects and nurtures them. Neither Mother Nature nor chance can program them to build sophisticated nests. Because all animals obey their Creator's directives, they display behavior that could not be expected of them.

With the 68th verse of the Sura 16 —"… Build dwellings in the mountains and the trees, and also in the structures which men erect"—God reveals that it is He Who tells the bees where to build their nests.

Many animal species suffer hardship in order to raise and protect their offspring, even risking death on occasion. Some migrate for hundreds of miles to their chosen nesting grounds, where they build sophisticated nests requiring much effort. A few, like the male praying mantis, die after mating; or—like the salmon—after laying their eggs. Others guard their eggs for many weeks, some even carrying their eggs in their mouths and therefore cannot feed.

All these acts of altruism serve an important purpose: survival of the species. The weak and vulnerable young can survive only if protected and cared for by strong adults. The chances of survival are next to nothing for a newborn deserted at birth or for eggs laid just anywhere. But living beings take it upon themselves to care for their defenseless young without any signs of laziness, hesitation or frustration. Each species fulfills its role, ordained by God, without fail.

Another interesting point is that those species that devote the greatest care and attention to protecting their eggs or young, are those that reproduce in the fewest numbers. Birds, for instance, lay only a limited number of eggs each year, but guard them meticulously. Likewise, larger mammals produce only one or two young, but take it upon themselves to protect and care for them for a very long time. Some fish and insects lay thousands of eggs at any one time; and mice have several litters per year. But they do not pay the same attention to their eggs or offspring. Even if only a few survive, they are enough to guarantee the continuation of the species, because of the original high numbers involved. Were they to try and show the same devotion to every single one of their offspring, there would be a significant damage done to the world's ecological balance. For example, were this the case with field mice, who reproduce in great numbers, their population would increase to such an extent that they would overrun the world.51Reproduction is a vital factor in the preservation of the ecological balances, but it is impossible for animals themselves to monitor and balance this factor by conscious control.

None of these animals is a rational being. They cannot know that they need to reproduce to begin with, nor that they should consider the balances of the ecosystem and act accordingly. However, natural balances are indeed preserved, and each animal exactly fulfills its responsibilities. This clearly shows that all living things are governed by the same authority. Nothing in nature is unsupervised or uncontrolled; all bow to God, their Creator, and act accordingly.

God says in the Qur'an that no creature could reproduce unless He wills it, and that He determines death as well as life:

God knows what every female bears and every shrinking of the womb and every swelling. Everything has its measure with Him. (Qur'an, 13: 8)

. . . And no fruit emerges from its husk, nor does any female get pregnant or give birth, without His knowledge. . . (Qur'an, 41: 47)

The kingdom of the heavens and earth belongs to God. He creates whatever He wills. He gives daughters to whoever He wishes; and He gives sons to whoever He wishes; or He gives them both sons and daughters; and He makes whoever He wishes barren. Truly He is All-Knowing, All-Powerful. (Qur'an, 42: 49-50)

|

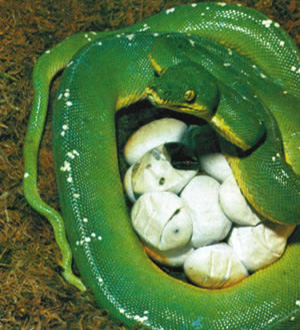

| The python cares for its eggs, even though most people would think otherwise. |

It is possible to see many species of birds, fish or reptiles displaying acts of great devotion and compassion. Many species of animals suffer much hardship to protect their next generation—concealing them, placing the eggs carefully to prevent their breaking, warming or protecting the young from excessive heat, removing them to safety in case of danger, even carrying them around in their mouths, and guarding them for weeks on end.

Pythons can be dangerous to other larger creatures, including man, but are very protective and devoted to their eggs. The female python lays approximately 100 eggs, then curls up over them. This action cools the eggs by shading them when it's too hot; when it is too cool, she warms them by vibrating her body. In this way, the female python prevents life-endangering threats to her eggs.52

Another interesting group of animals is the mouthbrooders—fish that incubate their spawn in their mouths. Some continue to keep them in their mouths even after the eggs hatch. Catfish, for example, swim around for weeks with their mouths full of their marble-sized eggs. Sometimes they gurgle with their mouths to increase the eggs' oxygen supply. After the eggs hatch, they stay in the mouth of the male catfish for a few more weeks. During this period, the male sustains himself by drawing from his fat reserves and hardly ever eats.53

Another species that carries its young in its mouth is the frog. Rhinoderma carries its spawn inside itself. In the mating season, the females lay their eggs onto the ground, and the males gather to form a protective shield around the eggs. As the eggs develop, they begin to wobble within their globes of jelly, signaling for the males to come forward. They pick up the eggs and take them into their vocal sacs, which are unusually large. The eggs develop inside. One day, the male frog retches several times, then opens up its mouth wide and fully developed froglets emerge from his mouth.54

Another species of frog, native to Australia, does not keep its eggs in a separate sac, but swallows them down to its stomach. But while the offspring inside the stomach are protected from the external world, still they are exposed to a great danger from the acidic stomach juices that can digest eggs. Therefore, if the female continues to secrete stomach juices as she usually does, she will digest her own young. But, this does not happen because preventive measures kick in. When the frog swallows her spawn, her stomach ceases to secrete digestive juices, so that the spawn are saved from being digested.55

|

| For weeks, this species of frog carries its own eggs attached around his hind legs. |

To guarantee the safety of their offspring, some other frogs use altogether different methods. For instance, after the Pipa toad spawns, the male frog gathers the eggs with his webbed feet and places them on the female's back. The eggs stick to her skin, which begins to swell, and the eggs are embedded in it. A thin membrane forms over the eggs. Within thirty hours, they sink far enough as to become invisible, and the back of the female frog is level once again. The eggs develop under her skin. After 15 days, the back of the frog begins to stir with the movements of tadpoles. On the 24th day, the young frogs penetrate the skin, emerge into the water, and they immediately seek a safe place to hide.56

The midwife toad, native to Europe, spends the best part of its life in holes on land in the proximity of water. It mates on land and, after the female has spawned, the male fertilizes her eggs. A quarter of an hour later, the male begins to stick the eggs together into strings, which he then bonds to his hind legs. Wherever the male goes over the coming few weeks, he drags the spawn along with him. When the eggs are ready to hatch, the male returns to the water, where he stays until all the tadpoles have emerged. He then returns to his hole in the ground.57

In all these examples, one important point must not be missed. The behavior of these frogs is in complete harmony with their physical characteristics. One of these frogs has a sac made for the spawn that extends right down the underside of its body. The frog could not possibly be conscious of this, but instead of swallowing the eggs, it takes them into its vocal sac as if it were. The other species of frog, because it lacks the faculty of thought and intellect, could not know that its digestive juices would harm its spawn, much less how to stop secreting it. No living creature is able to stop its stomach from secreting digestive juices. Yet another species has a back uniquely suited to carry its spawn. Its physical attributes and behavior are so complex that they couldn't possibly have developed by chance.

In each of these examples, there is an intrinsic design and plan. It is self-evident that God, the All-Knowing and All-Wise, has created these physical and behavioral characteristics in frogs, letting them be in harmony with one another as well as all the other living things. God, the Infinitely Compassionate and Merciful, protects all babies and offspring.

|

| 1. Many species of birds nest in colonies. In the picture below right, there are 70 eggs for every square meter, but the birds can always find their own eggs and young when they return from feeding. 2. Above: The rain-bird wets its breast feathers when the day is hot in order to cool its eggs. 3. Below left: The albatross. 4. Top right: The fairy tern does everything its eggs require during incubation. As these pictures demonstrate, birds tend their eggs carefully. They build nests to protect them and never leave them unattended. Beyond doubt, it is God, their sustainer and protector, Who inspires them to do so. |

God has given the instincts of protection and compassion not only to the creatures mentioned here. Similarly, the eggs and larvae of ants, termites, bees and other colony-forming insects are the central point of their care and attention. Ants keep their eggs and larvae in underground chambers built especially for that purpose. Worker ants frequently move them from chamber to chamber, according to fluctuations in humidity and temperature, going to and fro, carrying the larvae in their jaws. When their nest comes under attack by other creatures, the worker ants immediately evacuate these chambers and carry the larvae to safety outside the nest.58

Birds' care for their eggs is truly astonishing. For example, the little ringed plover lays four eggs in a hole in the ground. If the temperature rises dangerously, it plunges its abdomen in water and on its return, cools the eggs with the moisture on its feathers.59

Most egg-laying animals regulate the temperature of their eggs' environment. Water fowl, like ducks and geese, for example, cover their eggs with feathers that they pluck from their own own breasts. This prevents heat loss from the eggs.60

Burrowing Owls |

|

| Many species of birds employ various skills to protect their eggs from danger. For instance the burrowing owl builds its nest three meters (ten feet) underground, where it lays between 6 and 12 eggs. Males assist the females during the incubation period, and one or the other will always guard the entrance leading to their nest. Should a predatory bird try to enter, one of the birds will imitate the hissing sound of a snake—so well that the intruder is scared off.65 |

Like many smaller birds, swans maintain their eggs' warmth by sitting on them. The female frequently gets up and turns the eggs so they will warm evenly.61

For incubating its eggs, the phalarope bird uses an altogether different method. Once the female lays her eggs, her mate takes over the responsibility of looking after them. Sitting on the eggs, he soon loses the feathers on his breast and abdomen. This increases blood flow to these areas of skin, and the warmth is sufficient for the male to incubate the eggs in just over three weeks.62

Regulating the temperature in the nest is vital for the development of the eggs of all creatures. It is very significant that animals are most sensitive in this regard and regulate the temperature by a variety of methods. It's not likely that any bird, snake or ant should know the importance of proper temperature and then, all by itself, discover an appropriate method for keeping temperatures at the needed level. That knowledge must lie outside of these animals. To thinking people, God, the Creator of everything, reveals His endless wisdom by creating different qualities in countless different creatures.

Often these animals tire endlessly in the effort to look after their young. Birds, in particular, are often required to build nest after nest, in one breeding season. While providing for their young in one nest, they have to incubate the eggs in another. For instance, in the little ringed plover and the grebes, both male and female, spend their days between incubating the eggs in one nest and feeding their young in the other.63

More interestingly, in the water hen and window swallow species, the young in the first nest help raise of the younger birds in the second. Many bee-eater pairs aid other pairs. This type of cooperation among one another is common among birds.64 No doubt, every one of these acts of selfless devotion rocks the whole premise of the theory of evolution. Such higher behavior should not exist in a natural ecosystem that, according to the evolutionists, has been formed by random chance and is populated by creatures with no concern for any individual beyond themselves. However, countless examples of altruism and helpfulness prove that nature is not the product of chance, but has been created by a superior being.

|

| In the mating season, emperor penguins migrate for miles to their nesting grounds. |

This is yet another species that goes to great effort to protect its eggs, and shows an astonishing level of patience and endurance. These birds, native to the inhospitable conditions of Antarctica, migrate a few miles to suitable grounds in March or April (when winter begins in the Southern Hemisphere) in order to reproduce and raise their young. Around 25,000 penguins congregate to mate. In May or June, each female lays one egg. The pair will not build a nest for their egg, as their whole environment is a land of ice and snow. Nor will they lay their egg on the ice, because it would not withstand the cold and freeze instantly. That is why the female carries the egg on her feet. A few hours after the female lays the egg, the male joins her, and they stand breast to breast.

The male takes the egg from the female, both making sure that the egg doesn't make contact with the ice. He pushes his toes under the egg, then raises them to roll it onto his feet, doing this with utmost care and attention so as not to break the egg by accident. After this difficult exercise, he buries the egg in his feathers.

Producing the egg has almost exhausted the female penguin's fat reserves, and she must immediately return to the sea to find food and restore her body fat to its former level. This is why the male needs to incubate her egg. But this is a much more difficult incubation period than other birds experience, and requires much patience. A male penguin never puts the egg down on the ice and therefore, he is almost completely immobile. He can move for only a few meters by dragging his feet and using his tail like a third foot. He rests on his heels while raising his toes, to prevent the precious egg from rolling onto the ice to freeze. Because his feet are covered by feathers, the temperature there is 80 degrees Centigrade (176 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the outside air. The egg never gets chilled by the freezing cold.

As the Southern Hemisphere winter progresses, snowstorms begin to wreak havoc. Winds can reach speeds of 120-160 kilometers an hour (75-95 mph). Under these murderous conditions, the male penguins go without food for a month and hardly ever move, proving their dedication for their offspring. In order not to freeze, male penguins huddle closer together, forming a solid bloc. To prevent cold air from blowing in between them, they press their beaks against their chests and their necks curve to the horizontal, thus forming a feathered roof with no gaps in between. Those penguins on the fringes are forced to stomach all the harshness of the South Pole. Not for long, though, because they keep rotating so as to face the cold in turns, proving their solidarity. No one bird refuses to take his turn.

It is very significant indeed that thousands of penguins can live side by side under the harshest conditions without conflict. It would be very unlikely for man, blessed with consciousness and intellect, to live in harmony, considerate and unselfish, where such a conflict of interest exists. But penguins do not desert their eggs, despite these inhospitable conditions and the threats to their own lives. This deals a lethal blow to the evolutionists' claim that the weak die out and perish, destroyed by the strong. Instead, nature is where the vulnerable are protected and cared for, despite all the hardships involved.

|

| Both male and female emperor penguins show selfless devotion for their young. |

After a most difficult 60 days, the penguins' eggs hatch. The males, even after 60 days of resisting the cold without any food, are still preoccupied with their young rather than themselves. The new arrivals need nourishment. From their gullets, the male penguins produce a milky secretion which they feed to their offspring. At this critical moment, the females return. They call for their mates, who return their call. The pairs recognize one another by their voices during the mating ritual. Despite their three-month separation, they recognize each other immediately, and their ability to do so is a God-given gift.

The females have full crops and regurgitate in front of the chicks, which then eat their first real meal. You might expect the male, upon the female's return, to leave its offspring to mind its own business, but not so: he looks after the chick for another ten days, keeping it warm on his feet. Only then does he return to the sea to find his first meal in four months.

After about three to four weeks at sea, he returns to take over the responsibility of looking after the young from the female, who then sets off to feed in the ocean again.

In the first stages of their lives, baby penguins cannot generate their own body heat. If left alone, they die within minutes. This is why the male and female penguin take turns feeding their offspring and protecting it from the cold, not hesitating to endanger their own lives in this cause.66

God directs male and female penguins to cooperate in protecting their eggs and young under the worst conditions, sharing the work at the risk of death. They never desert their young at any cost, even for a single moment. Under those conditions, a creature devoid of reason could be expected to soon abandon its egg in order to find for itself. But thanks to the feeling of protection that God inspires in them, penguins guard the egg not for hours or days, but for months.

25.Russell Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1978), p. 4.

26. Ibid., p. 4.

27.Peter J. B. Slater, The Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1987), p. 87.

28.Glenn Oeland, "Emperors of the Ice", National Geographic, Vol. 189, no. 3, March 1996, p. 64.

29.Giovanni G. Bellani, Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid (When The Bird Makes Its Nest) (Arthaud, 1996), p. 85.

30.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, pp. 13-14.

31.Bellani, Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid, pp. 24, 90.

32. Ibid., 89.

33. David Attenborough, The Life of Birds (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1998), pp. 233-234.

34. Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, p. 47.

35.Attenborough, The Life of Birds, p. 234.

36.Slater, The Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, p. 42; and Attenborough, Life of Birds, pp. 234-235.

37."Kalahari Gems," www.safricavoyage.com/kalahari.htm

38.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, p. 13.

39.Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 225.

40.Freedman,How Animals Defend Their Young, p.14.

41. Ibid., p. 14.

42.Ibid., p. 47.

43.Attenborough, Life of Birds, pp. 149-151.

44.The Marvels of Animal Behavior (National Geopraphic Society, 1972), p. 301; and Attenborough, Life of Birds, p. 228.

45.Curt Kosswig, Genel Zooloji (General Zoology) (Istanbul: 1945), pp. 145-148.

46.Thor Larsen, "Polar Bear: Lonely Nomad of the North", National Geographic, April 1971, p. 587.

47. International Wildlife, November-December 1994, p. 15.

48.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, p. 15.

49.Ibid., p. 16.

50.Ibid., p. 17.

51.Ibid., p. 6.

52.Tony Seddon, Animal Parenting (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1989), p. 27.

53.Freedman, How Animals Defend Their Young, p. 19.

54.David Attenborough, Life on Earth (Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd, 1979), p. 147.

55.Seddon, Animal Parenting, p. 31.

56.Attenborough, Life on Earth, p. 145.

57.Ibid., p. 146.

58.Seddon, Animal Parenting, p. 19.

59.Bellani, Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid, p. 59.

60.Attenborough, The Life of Birds, p. 241.

61.Roger B. Hirschland, How Animals Care for Their Babies (Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1987), p. 6.

62."When This Water Bird Is Hungry, It Simply Summons Food to the Surface", National Wildlife, Oct-Nov. 1998

63.Bellani, Quand L'oiseau Fait Son Nid, p. 23.

64.Ibid., p. 20.

65.Ibid., pp. 104-105.

66.Attenborough, Life of Birds, pp. 288-292.