Morphological Distance

For some people, the very concept of natural history implies the theory of evolution. The reason for this is the heavy propaganda that has been carried out. Natural history museums in most countries are under the control of materialist evolutionary biologists, and it is they who describe the exhibits in them. They invariably describe creatures that lived in prehistory and their fossil remains in terms of Darwinian concepts. One result of this is that most people think that natural history is equivalent to the concept of evolution.

However, the facts are very different. Natural history reveals that different classes of life emerged on the earth not through any evolutionary process, but all at once, and with all their complex structures fully developed right from the start. Different living species appeared completely independently of one another, and with no "transitional forms" between them.

In this chapter, we shall examine real natural history, taking the fossil record as our basis.

Biologists place living things into different classes. This classification, known as "taxonomy," or "systematics," goes back as far as the eighteenth-century Swedish scientist Carl von Linné, known as Linnaeus. The system of classification established by Linnaeus has continued and been developed right up to the present day.

There are hierarchical categories in this classificatory system. Living things are first divided into kingdoms, such as the plant and animal kingdoms. Then these kingdoms are sub-divided into phyla, or categories. Phyla are further divided into subgroups. From top to bottom, the classification is as follows:

Today, the great majority of biologists accept that there are five (or six) separate kingdoms. As well as plants and animals, they consider fungi, protista (single-celled creatures with a cell nucleus, such as amoebae and some algae), and monera (single-celled creatures with no cell nucleus, such as bacteria), as separate kingdoms. Sometimes the bacteria are subdivided into eubacteria and archaebacteria, for six kingdoms, or, on some accounts, three "superkingdoms" (eubacteria, archaebacteria and eukarya). The most important of all these kingdoms is without doubt the animal kingdom. And the largest division within the animal kingdom, as we saw earlier, are the different phyla. When designating these phyla, the fact that each one possesses completely different physical structures should always be borne in mind. Arthropoda (insects, spiders, and other creatures with jointed limbs), for instance, are a phylum by themselves, and all the animals in the phylum have the same fundamental physical structure. The phylum called Chordata includes those creatures with the notochord, or, most commonly, a spinal column. All the animals with the spinal column such as fish, birds, reptiles, and mammals that we are familiar with in daily life are in a subphylum of Chordata known as vertebrates.

There are around 35 different phyla of animals, including the Mollusca, which include soft-bodied creatures such as snails and octopuses, or the Nematoda, which include diminutive worms. The most important feature of these categories is, as we touched on earlier, that they possess totally different physical characteristics. The categories below the phyla possess basically similar body plans, but the phyla are very different from one another.

After this general information about biological classification, let us now consider the question of how and when these phyla emerged on earth.

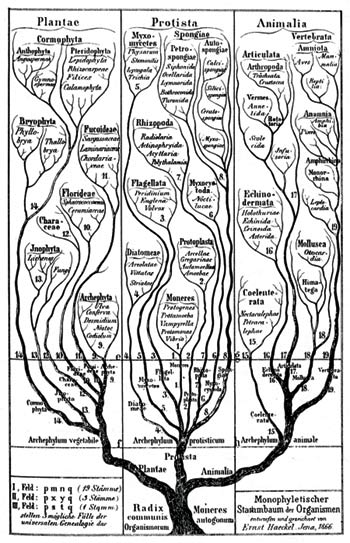

The so-called "tree of life" drawn by the evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel in 1866.

Let us first consider the Darwinist hypothesis. As we know, Darwinism proposes that life developed from one single common ancestor, and took on all its varieties by a series of tiny changes. In that case, life should first have emerged in very similar and simple forms. And according to the same theory, the differentiation between, and growing complexity in, living things must have happened in parallel over time.

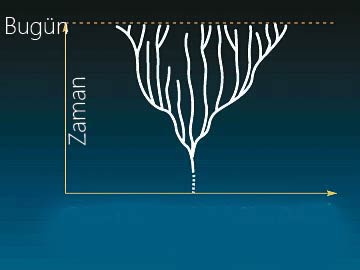

In short, according to Darwinism, life must be like a tree, with a common root, subsequently splitting up into different branches. And this hypothesis is constantly emphasized in Darwinist sources, where the concept of the "tree of life" is frequently employed. According to this tree concept, phyla -the fundamental units of classification between living things- came about by stages, as in the diagram to the left. According to Darwinism, one phylum must first emerge, and then the other phyla must slowly come about with minute changes over very long periods of time. The Darwinist hypothesis is that the number of animal phyla must have gradually increased in number. The diagram to the side shows the gradual increase in the number of animal phyla according to the Darwinian view.

According to Darwinism, life must have developed in this way. But is this really how it happened?

Definitely not. Quite the contrary: animals have been very different and complex since the moment they first emerged. All the animal phyla known today emerged at the same time, in the middle of the geological period known as the Cambrian Age. The Cambrian Age is a geological period estimated to have lasted some 65 million years, approximately between 570 to 505 million years ago. But the period of the abrupt appearance of major animal groups fit in an even shorter phase of the Cambrian, often referred to as the "Cambrian explosion." Stephen C. Meyer, P. A. Nelson, and Paul Chien, in a 2001 article based on a detailed literature survey, dated 2001, note that the "Cambrian explosion occurred within an exceedingly narrow window of geologic time, lasting no more than 5 million years."56

Before then, there is no trace in the fossil record of anything apart from single-celled creatures and a few very primitive multicellular ones. All animal phyla emerged completely formed and all at once, in the very short period of time represented by the Cambrian explosion. (Five million years is a very short time in geological terms!)

The Fossil Record Denies the Theory of Evolution

Morphological Distance

1. Present

2. Time

Natural History According to the Theory of Evolution

Morphological Distance

t. Time

1. Present

2. Cambrian

3. Pre-cambrian

True Natural History as Revealed by the Fossil Record

The theory of evolution maintains that different groups of living things (phyla) developed from a common ancestor and grew apart with the passing of time. The diagram above states this claim: According to Darwinism, living things grew apart from one another like the branches on a tree.

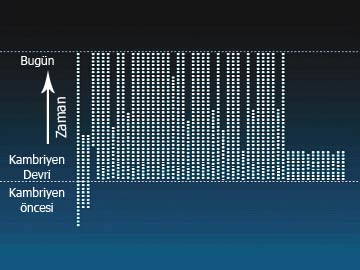

But the fossil record shows just the opposite. As can be seen from the diagram below, different groups of living things emerged suddenly with their different structures. Some 100 phyla suddenly emerged in the Cambrian Age. Subsequently, the number of these fell rather than rose (because some phyla became extinct). (Fromwww.arn.org)

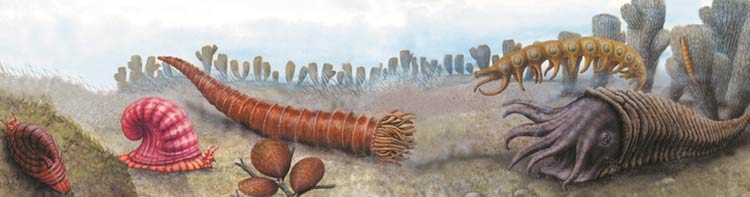

The fossils found in Cambrian rocks belong to very different creatures, such as snails, trilobites, sponges, jellyfish, starfish, shellfish, etc. Most of the creatures in this layer have complex systems and advanced structures, such as eyes, gills, and circulatory systems, exactly the same as those in living specimens. These structures are at one and the same time very advanced, and very different.

This illustration portrays living things with complex structures from the Cambrian Age. The emergence of such different creatures with no preceding ancestors completely invalidates Darwinist theory.

Richard Monastersky, a staff writer at ScienceNews magazine states the following about the "Cambrian explosion," which is a deathtrap for evolutionary theory:

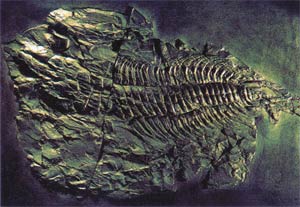

Marrella: One of the interesting fossil creatures found in the Burgess Shale fossil bed.

A half-billion years ago, ...the remarkably complex forms of animals we see today suddenly appeared. This moment, right at the start of Earth's Cambrian Period, some 550 million years ago, marks the evolutionary explosion that filled the seas with the world's first complex creatures.57

The same article also quotes Jan Bergström, a paleontologist who studied the early Cambrian deposits in Chengjiang, China, as saying, "The Chengjiang fauna demonstrates that the large animal phyla of today were present already in the early Cambrian and that they were as distinct from each other as they are today."58

How the earth came to overflow with such a great number of animal species all of a sudden, and how these distinct types of species with no common ancestors could have emerged, is a question that remains unanswered by evolutionists. The Oxford University zoologist Richard Dawkins, one of the foremost advocates of evolutionist thought in the world, comments on this reality that undermines the very foundation of all the arguments he has been defending:

For example the Cambrian strata of rocks… are the oldest ones in which we find most of the major invertebrate groups. And we find many of them already in an advanced state of evolution, the very first time they appear. It is as though they were just planted there, without any evolutionary history.59

Phillip Johnson, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley who is also one of the world's foremost critics of Darwinism, describes the contradiction between this paleontological truth and Darwinism:

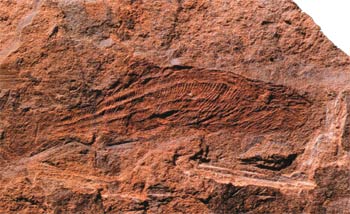

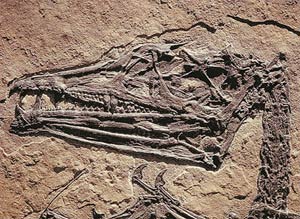

A fossil from the Cambrian Age

Darwinian theory predicts a "cone of increasing diversity," as the first living organism, or first animal species, gradually and continually diversified to create the higher levels of taxonomic order. The animal fossil record more resembles such a cone turned upside down, with the phyla present at the start and thereafter decreasing.60

As Phillip Johnson has revealed, far from its being the case that phyla came about by stages, in reality they all came into being at once, and some of them even became extinct in later periods. The diagrams on page 53 reveal the truth that the fossil record has revealed concerning the origin of phyla.

As we can see, in the Precambrian Age there were three different phyla consisting of single-cell creatures. But in the Cambrian Age, some 60 to 100 different animal phyla emerged all of a sudden. In the age that followed, some of these phyla became extinct, and only a few have come down to our day.

Roger Lewin discusses this extraordinary fact, which totally demolishes all the Darwinist assumptions about the history of life:

Described recently as "the most important evolutionary event during the entire history of the Metazoa," the Cambrian explosion established virtually all the major animal body forms — Baupläne or phyla — that would exist thereafter, including many that were "weeded out" and became extinct. Compared with the 30 or so extant phyla, some people estimate that the Cambrian explosion may have generated as many as 100.61

Interesting Spines:

One of the creatures which suddenly emerged in the Cambrian Age was Hallucigenia, seen at top left. And as with many other Cambrian fossils, it has spines or a hard shell to protect it from attack by enemies. The question that evolutionists cannot answer is, "How could they have come by such an effective defense system at a time when there were no predators around?" The lack of predators at the time makes it impossible to explain the matter in terms of natural selection.

Lewin continues to call this extraordinary phenomenon from the Cambrian Age an "evolutionary event," because of the loyalty he feels to Darwinism, but it is clear that the discoveries so far cannot be explained by any evolutionary approach.

What is interesting is that the new fossil findings make the Cambrian Age problem all the more complicated. In its February 1999 issue, Trends in Genetics (TIG), a leading science journal, dealt with this issue. In an article about a fossil bed in the Burgess Shale region of British Colombia, Canada, it confessed that fossil findings in the area offer no support for the theory of evolution.

The Burgess Shale fossil bed is accepted as one of the most important paleontological discoveries of our time. The fossils of many different species uncovered in the Burgess Shale appeared on earth all of a sudden, without having been developed from any pre-existing species found in preceding layers. TIG expresses this important problem as follows:

It might seem odd that fossils from one small locality, no matter how exciting, should lie at the center of a fierce debate about such broad issues in evolutionary biology. The reason is that animals burst into the fossil record in astonishing profusion during the Cambrian, seemingly from nowhere. Increasingly precise radiometric dating and new fossil discoveries have only sharpened the suddenness and scope of this biological revolution. The magnitude of this change in Earth's biota demands an explanation. Although many hypotheses have been proposed, the general consensus is that none is wholly convincing.62

These "not wholly convincing" hypotheses belong to evolutionary paleontologists. TIG mentions two important authorities in this context, Stephen Jay Gould and Simon Conway Morris. Both have written books to explain the "sudden appearance of living beings" from the evolutionist standpoint. However, as also stressed by TIG, neither Wonderful Life by Gould nor The Crucible of Creation: The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals by Simon Conway Morris has provided an explanation for the Burgess Shale fossils, or for the fossil record of the Cambrian Age in general.

Another illustration showing living things from the Cambrian Age.

Deeper investigation into the Cambrian Explosion shows what a great dilemma it creates for the theory of evolution. Recent findings indicate that almost all phyla, the most basic animal divisions, emerged abruptly in the Cambrian period. An article published in the journal Science in 2001 says: "The beginning of the Cambrian period, some 545 million years ago, saw the sudden appearance in the fossil record of almost all the main types of animals (phyla) that still dominate the biota today."63 The same article notes that for such complex and distinct living groups to be explained according to the theory of evolution, very rich fossil beds showing a gradual developmental process should have been found, but this has not yet proved possible:

This differential evolution and dispersal, too, must have required a previous history of the group for which there is no fossil record.64

The picture presented by the Cambrian fossils clearly refutes the assumptions of the theory of evolution, and provides strong evidence for the involvement of a "supernatural" being in their creation. Douglas Futuyma, a prominent evolutionary biologist, admits this fact:

Organisms either appeared on the earth fully developed or they did not. If they did not, they must have developed from pre-existing species by some process of modification. If they did appear in a fully developed state, they must indeed have been created by some omnipotent intelligence.65

The fossil record clearly indicates that living things did not evolve from primitive to advanced forms, but instead emerged all of a sudden in a fully formed state. This provides evidence for saying that life did not come into existence through random natural processes, but through an act of intelligent creation. In an article called "the Big Bang of Animal Evolution" in the leading journal Scientific American, Jeffrey S. Levinton, Professor of Ecology and Evolution at the State University of New York, accepts this reality, albeit unwillingly, saying "Therefore, something special and very mysterious -some highly creative "force"- existed then."66

Another fact that puts the theory of evolution into a deep quandary about the Cambrian Explosion is genetic comparisons between different living taxa. The results of these comparisons reveal that animal taxa considered to be "close relatives" by evolutionists until quite recently, are in fact genetically very different, which totally refutes the "intermediate form" hypothesis—which only exists theoretically. An article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, in 2000 reports that recent DNA analyses have rearranged taxa that used to be considered "intermediate forms" in the past:

DNA sequence analysis dictates new interpretation of phylogenic trees. Taxa that were once thought to represent successive grades of complexity at the base of the metazoan tree are being displaced to much higher positions inside the tree. This leaves no evolutionary ''intermediates'' and forces us to rethink the genesis of bilaterian complexity.67

In the same article, evolutionist writers note that some taxa which were considered "intermediate" between groups such as sponges, cnidarians and ctenophores, can no longer be considered as such because of these new genetic findings. These writers say that they have "lost hope" of constructing such evolutionary family trees:

Trilobite eyes, with their doublet structure and hundreds of tiny lensed units, were a wonder of creation.

Darwin said that if his theory was correct, the long periods before the trilobites should have been full of their ancestors. But not one of these creatures predicted by Darwin has ever been found.

The new molecular based phylogeny has several important implications. Foremost among them is the disappearance of "intermediate" taxa between sponges, cnidarians, ctenophores, and the last common ancestor of bilaterians or "Urbilateria."...A corollary is that we have a major gap in the stem leading to the Urbilataria. We have lost the hope, so common in older evolutionary reasoning, of reconstructing the morphology of the "coelomate ancestor" through a scenario involving successive grades of increasing complexity based on the anatomy of extant "primitive" lineages.68

One of the most interesting of the many different species that suddenly emerged in the Cambrian Age is the now-extinct trilobites. Trilobites belonged to the Arthropoda phylum, and were very complicated creatures with hard shells, articulated bodies, and complex organs. The fossil record has made it possible to carry out very detailed studies of trilobites' eyes. The trilobite eye is made up of hundreds of tiny facets, and each one of these contains two lens layers. This eye structure is a real wonder of creation. David Raup, a professor of geology at Harvard, Rochester, and Chicago Universities, says, "the trilobites 450 million years ago used an optimal design which would require a well trained and imaginative optical engineer to develop today."69

The extraordinarily complex structure even in trilobites is enough to invalidate Darwinism on its own, because no complex creatures with similar structures lived in previous geological periods, which goes to show that trilobites emerged with no evolutionary process behind them. A 2001 Science article says:

Cladistic analyses of arthropod phylogeny revealed that trilobites, like eucrustaceans, are fairly advanced "twigs" on the arthropod tree. But fossils of these alleged ancestral arthropods are lacking. ...Even if evidence for an earlier origin is discovered, it remains a challenge to explain why so many animals should have increased in size and acquired shells within so short a time at the base of the Cambrian.70

The Fish of the Cambrian

Until 1999, the question of whether any vertebrates were present in the Cambrian was limited to the discussion about Pikaia. But that year a stunning discovery deepened the evolutionary impasse regarding the Cambrian explosion: Chinese paleontologists at Chengjiang fauna discovered the fossils of two fish species that were about 530 million years old, a period known as the Lower Cambrian. Thus, it became crystal clear that along with all other phyla, the subphylum Vertebrata (Vertebrates) was also present in the Cambrian, without any evolutionary ancestors.

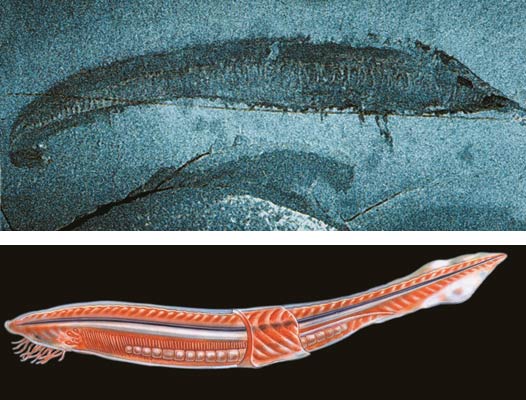

The two distinct fish species of the Cambrian, Haikouichthys ercaicunensis and Myllokunmingia fengjiaoa.

Very little was known about this extraordinary situation in the Cambrian Age when Charles Darwin was writing The Origin of Species. Only since Darwin's time has the fossil record revealed that life suddenly emerged in the Cambrian Age, and that trilobites and other invertebrates came into being all at once. For this reason, Darwin was unable to treat the subject fully in the book. But he did touch on the subject under the heading "On the sudden appearance of groups of allied species in the lowest known fossiliferous strata," where he wrote the following about the Silurian Age (a name which at that time encompassed what we now call the Cambrian):

Consequently, if my theory be true, it is indisputable that before the lowest Silurian stratum was deposited, long periods elapsed, as long as, or probably far longer than, the whole interval from the Silurian age to the present day; and that during these vast, yet quite unknown, periods of time, the world swarmed with living creatures. To the question why we do not find records of these vast primordial periods, I can give no satisfactory answer.71

Darwin said "If my theory be true, [the Cambrian] Age must have been full of living creatures." As for the question of why there were no fossils of these creatures, he tried to supply an answer throughout his book, using the excuse that "the fossil record is very lacking." But nowadays the fossil record is quite complete, and it clearly reveals that creatures from the Cambrian Age did not have ancestors. This means that we have to reject that sentence of Darwin's which begins "If my theory be true." Darwin's hypotheses were invalid, and for that reason, his theory is mistaken.

The Origin of Fish

The fossil record shows that fish, like other kinds of living things, also emerged suddenly and already in possession of all their unique structures. In other words, fish were created, not evolved.

Left: Fossil fish called Birkenia from Scotland. This creature, estimated to be some 420 million years old, is about 4 cm. long.

Right: Group of fossil fish from the Mesozoic Age.

Left: Fossil shark of the Stethacanthus genus, some 330 million years old.

Right: Fossil fish approximately 360 million years old from the Devonian Age. Called Osteolepis panderi, it is about 20 cm. long and closely resembles present-day fish.

110-million-year-old fossil fish

from the Santana fossil bed in Brazil.

The record from the Cambrian Age demolishes Darwinism, both with the complex bodies of trilobites, and with the emergence of very different living bodies at the same time. Darwin wrote "If numerous species, belonging to the same genera or families, have really started into life all at once, the fact would be fatal to the theory of descent with slow modification through natural selection."72 -that is, the theory at the heart of in his book. But as we saw earlier, 60 to 100 different animal phyla started into life in the Cambrian Age, all together and at the same time, let alone small categories such as species. This proves that the picture which Darwin had described as "fatal to the theory" is in fact the case. This is why the Swiss evolutionary paleoanthropologist Stefan Bengtson, who confesses the lack of transitional links while describing the Cambrian Age, makes the following comment: "Baffling (and embarrassing) to Darwin, this event still dazzles us."73

Another matter that needs to be dealt with regarding trilobites is that the 530-million-year-old compound structure in these creatures' eyes has come down to the present day completely unchanged. Some insects today, such as bees and dragonflies, possess exactly the same eye structure.74 This discovery deals yet another "fatal blow" to the theory of evolution's claim that living things develop from the primitive to the complex.

As we said at the beginning, one of the phyla that suddenly emerged in the Cambrian Age is the Chordata, those creatures with a central nervous system contained within a braincase and a notochord or spinal column. Vertebrates are a subgroup of chordates. Vertebrates, divided into such fundamental classes as fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, are probably the most dominant creatures in the animal kingdom.

Because evolutionary paleontologists try to view every phylum as the evolutionary continuation of another phylum, they claim that the Chordata phylum evolved from another, invertebrate one. But the fact that, as with all phyla, the members of the Chordata emerged in the Cambrian Age invalidates this claim right from the very start.

As stated earlier, 530-million-year-old Cambrian fish fossils were discovered in 1999, and this striking discovery was sufficient to demolish all the claims of the theory of evolution on this subject.

The oldest member of the Chordata phylum identified from the Cambrian Age is a sea-creature called Pikaia, which with its long body reminds one at first sight of a worm.75 Pikaia emerged at the same time as all the other species in the phylum which could be proposed as its ancestor, and with no intermediate forms between them. Professor Mustafa Kuru, a Turkish evolutionary biologist, says in his book Vertebrates:

There is no doubt that chordates evolved from invertebrates. However, the lack of transitional forms between invertebrates and chordates causes people to put forward many assumptions.76

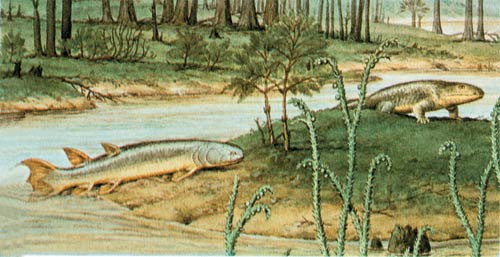

The "transition from water to land" scenario, often maintained in evolutionist publications in imaginary diagrams like the one above, is often presented with a Lamarckian rationale, which is clearly pseudoscience.

If there is no transitional form between chordates and invertebrates, then how can one say "there is no doubt that chordates evolved from invertebrates?" Accepting an assumption which lacks supporting evidence, without entertaining any doubts, is surely not a scientific approach, but a dogmatic one. After this statement, Professor Kuru discusses the evolutionist assumptions regarding the origins of vertebrates, and once again confesses that the fossil record of chordates consists only of gaps:

The views stated above about the origins of chordates and evolution are always met with suspicion, since they are not based on any fossil records.77

Evolutionary biologists sometimes claim that the reason why there exist no fossil records regarding the origin of vertebrates is because invertebrates have soft tissues and consequently leave no fossil traces. However this explanation is entirely unrealistic, since there is an abundance of fossil remains of invertebrates in the fossil record. Nearly all organisms in the Cambrian period were invertebrates, and tens of thousands of fossil examples of these species have been collected. For example, there are many fossils of soft-tissued creatures in Canada's Burgess Shale beds. (Scientists think that invertebrates were fossilized, and their soft tissues kept intact in regions such as Burgess Shale, by being suddenly covered in mud with a very low oxygen content.78)

The theory of evolution assumes that the first Chordata, such as Pikaia, evolved into fish. However, just as with the case of the supposed evolution of Chordata, the theory of the evolution of fish also lacks fossil evidence to support it. On the contrary, all distinct classes of fish emerged in the fossil record all of a sudden and fully-formed. There are millions of invertebrate fossils and millions of fish fossils; yet there is not even one fossil that is midway between them.

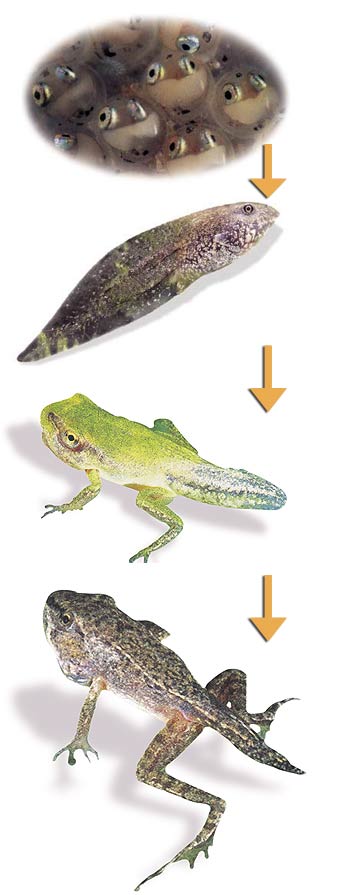

There was no "evolutionary" process in the origin of frogs. The oldest known frogs were completely different from fish, and emerged with all their own peculiar features. Frogs in our time possess the same features. There is no difference between the frog found preserved in amber in the Dominican Republic and specimens living today.

Robert Carroll admits the evolutionist impasse on the origin of several taxa among the early vertebrates:

We still have no evidence of the nature of the transition between cephalochordates and craniates. The earliest adequately known vertebrates already exhibit all the definitive features of craniates that we can expect to have preserved in fossils. No fossils are known that document the origin of jawed vertebrates.79

Another evolutionary paleontologist, Gerald T. Todd, admits a similar fact in an article titled "Evolution of the Lung and the Origin of Bony Fishes":

All three subdivisions of bony fishes first appear in the fossil record at approximately the same time. They are already widely divergent morphologically, and are heavily armored. How did they originate? What allowed them to diverge so widely? How did they all come to have heavy armor? And why is there no trace of earlier, intermediate forms?80

The Origin of Tetrapods

Quadrupeds (or Tetrapoda) is the general name given to vertebrate animals dwelling on land. Amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals are included in this class. The assumption of the theory of evolution regarding quadrupeds holds that these living things evolved from fish living in the sea. However, this claim poses contradictions, in terms of both physiology and anatomy. Furthermore, it lacks any basis in the fossil record.

A fish would have to undergo great modifications to adapt to land. Basically, its respiratory, excretory and skeletal systems would all have to change. Gills would have to change into lungs, fins would have to acquire the features of feet so that they could carry the weight of the body, kidneys and the whole excretory system would have to be transformed to work in a terrestrial environment, and the skin would need to acquire a new texture to prevent water loss. Unless all these things happened, a fish could only survive on land for a few minutes.

So, how does the evolutionist view explain the origin of land-dwelling animals? Some shallow comments in evolutionist literature are mainly based on a Lamarckian rationale. For instance, regarding the transformation of fins into feet, they say, "Just when fish started to creep on land, fins gradually became feet." Ali Demirsoy, one of the foremost evolutionist scientists in Turkey, writes the following: "Maybe the fins of lunged fish changed into amphibian feet as they crept through muddy water."81

As mentioned earlier, these comments are based on a Lamarckian rationale, since the comment is essentially based on the improvement of an organ through use and the passing on of this trait to subsequent generations. It seems that the theory postulated by Lamarck, which collapsed a century ago, still has a strong influence on the subconscious minds of evolutionary biologists today.

If we set aside these Lamarckist, and therefore unscientific, scenarios, we have to turn our attention to scenarios based on mutation and natural selection. However, when these mechanisms are examined, it can be seen that the transition from water to land is at a complete impasse.

Let us imagine how a fish might emerge from the sea and adapt itself to the land: If the fish does not undergo a rapid modification in terms of its respiratory, excretory and skeletal systems, it will inevitably die. The chain of mutations that needs to come about has to provide the fish with a lung and terrestrial kidneys, immediately. Similarly, this mechanism should transform the fins into feet and provide the sort of skin texture that will hold water inside the body. What is more, this chain of mutations has to take place during the lifespan of one single animal.

No evolutionary biologist would ever advocate such a chain of mutations. The implausible and nonsensical nature of the very idea is obvious. Despite this fact, evolutionists put forward the concept of "preadaptation," which means that fish acquire the traits they will need while they are still in the water. Put briefly, the theory says that fish acquire the traits of land-dwelling animals before they even feel the need for these traits, while they are still living in the sea.

Nevertheless, such a scenario is illogical even when viewed from the standpoint of the theory of evolution. Surely, acquiring the traits of a land-dwelling living animal would not be advantageous for a marine animal. Consequently, the proposition that these traits occurred by means of natural selection rests on no rational grounds. On the contrary, natural selection should eliminate any creature which underwent "preadaptation," since acquiring traits which would enable it to survive on land would surely place it at a disadvantage in the sea.

In brief, the scenario of "transition from sea to land" is at a complete impasse. This is why Henry Gee, the editor of Nature, considers this scenario as an unscientific story:

Conventional stories about evolution, about 'missing links', are not in themselves testable, because there is only one possible course of events — the one implied by the story. If your story is about how a group of fishes crawled onto land and evolved legs, you are forced to see this as a once-only event, because that's the way the story goes. You can either subscribe to the story or not — there are no alternatives.82

The impasse does not only come from the alleged mechanisms of evolution, but also from the fossil record or the study of living tetrapods. Robert Carroll has to admit that "neither the fossil record nor study of development in modern genera yet provides a complete picture of how the paired limbs in tetrapods evolved…"83

The beings claimed to represent the transition from fish to tetrapods have been several fish and amphibian genera, none of which bears transitional form characteristics.

Evolutionist natural historians traditionally refer to coelacanths (and the closely-related, extinct Rhipidistians) as the most probably ancestors of quadrupeds. These fish come under the Crossopterygian subclass. Evolutionists invest all their hopes in them simply because their fins have a relatively "fleshy" structure. Yet these fish are not transitional forms; there are huge anatomical and physiological differences between this class and amphibians.

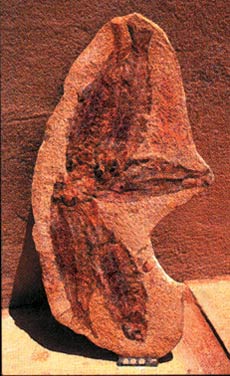

An Eusthenopteron foordi fossil from the Later Devonian Age found in Canada.

It is because of the huge anatomical differences between them that fish cannot be considered the evolutionary ancestors of amphibians. Two examples are Eusthenopteron (an extinct fish) and Acanthostega (an extinct amphibian), the two favorite subjects for most of the contemporary evolutionary scenarios regarding tetrapod origins. Robert Carroll, in his Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, makes the following comment about these allegedly related forms:

Eusthenopteron and Acanthostega may be taken as the end points in the transition between fish and amphibians. Of 145 anatomical features that could be compared between these two genera, 91 showed changes associated with adaptation to life on land… This is far more than the number of changes that occurred in any one of the transitions involving the origin of the fifteen major groups of Paleozoic tetrapods.84

Ninety-one differences over 145 anatomical features… And evolutionists believe that all these were redesigned through a process of random mutations in about 15 million years.85 To believe in such a scenario may be necessary for the sake of evolutionary theory, but it is not scientifically and rationally sound. This is true for all other versions of the fish-amphibian scenario, which differ according to the candidates that are chosen to be the transitional forms. Henry Gee, the editor of Nature, makes a similar comment on the scenario based on Ichthyostega, another extinct amphibian with very similar characteristics to Acanthostega:

A statement that Ichthyostega is a missing link between fishes and later tetrapods reveals far more about our prejudices than about the creature we are supposed to be studying. It shows how much we are imposing a restricted view on reality based on our own limited experience, when reality may be larger, stranger, and more different than we can imagine.86

Another remarkable feature of amphibian origins is the abrupt appearance of the three basic amphibian categories. Carroll notes that "The earliest fossils of frogs, caecilians, and salamanders all appear in the Early to Middle Jurassic. All show most of the important attributes of their living descendants."87 In other words, these animals appeared abruptly and did not undergo any "evolution" since then.

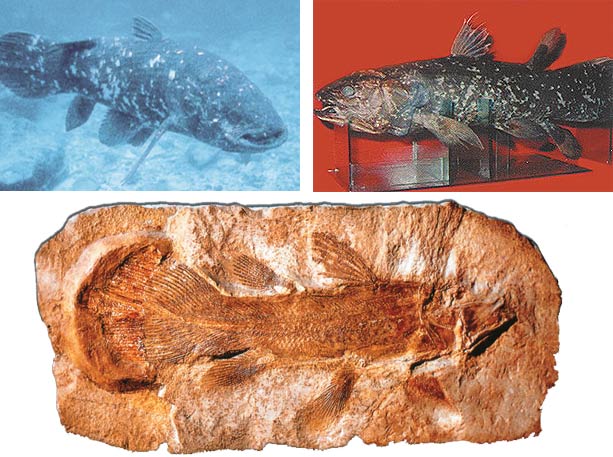

Fish that come under the coelacanth family were once accepted as strong evidence for transitional forms. Basing their argument on coelacanth fossils, evolutionary biologists proposed that this fish had a primitive (not completely functioning) lung. Many scientific publications stated the fact, together with drawings showing how coelacanths passed to land from water. All these rested on the assumption that the coelacanth was an extinct species.

When they only had fossils of coelacanths, evolutionary paleontologists put forward a number of Darwinist assumptions regarding them; however, when living examples were found, all these assumptions were shattered.

Below, examples of living coelacanths. The picture on the right shows the latest specimen of coelacanth, found in Indonesia in 1998.

However on December 22, 1938, a very interesting discovery was made in the Indian Ocean. A living member of the coelacanth family, previously presented as a transitional form that had become extinct 70 million years ago, was caught! The discovery of a "living" prototype of the coelacanth undoubtedly gave evolutionists a severe shock. The evolutionary paleontologist J. L. B. Smith said, "If I'd meet a dinosaur in the street I wouldn't have been more astonished."88 In the years to come, 200 coelacanths were caught many times in different parts of the world.

Living coelacanths revealed how groundless the speculation regarding them was. Contrary to what had been claimed, coelacanths had neither a primitive lung nor a large brain. The organ that evolutionist researchers had proposed as a primitive lung turned out to be nothing but a fat-filled swimbladder.89 Furthermore, the coelacanth, which was introduced as "a reptile candidate preparing to pass from sea to land," was in reality a fish that lived in the depths of the oceans and never approached nearer than 180 meters from the surface.90

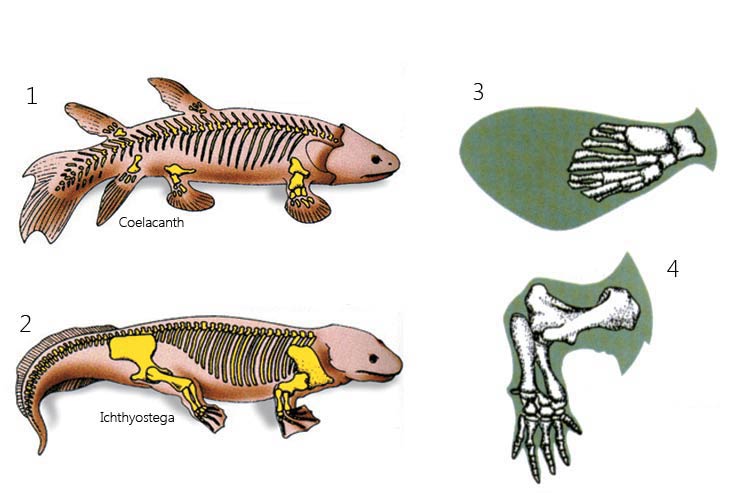

bones are not attached to the backbone

bones are attached to the backbone

Coelacanth's fin

Ichthyostega's feet

The Difference Between Fins and Feet

The fundamental reason why evolutionists imagine coelacanths and similar fish to be "the ancestor of land animals" is that they have bony fins. They imagine that these gradually turned into feet. However, there is a fundamental difference between fish bones and the feet of land animals such as Ichthyostega: As shown in Picture 1, the bones of the coelacanth are not attached to the backbone; however, those of Ichthyostega are, as shown in Picture 2. For this reason, the claim that these fins gradually developed into feet is quite unfounded. Furthermore, the structure of the bones in coelacanth fins is very different from that in the bones in Ichthyostega feet, as seen in Pictures 3 and 4.

Following this, the coelacanth suddenly lost all its popularity in evolutionist publications. Peter Forey, an evolutionary paleontologist, says in an article of his in Nature:

The discovery of Latimeria raised hopes of gathering direct information on the transition of fish to amphibians, for there was then a long-held belief that coelacanths were close to the ancestry of tetrapods. ...But studies of the anatomy and physiology of Latimeria have found this theory of relationship to be wanting and the living coelacanth's reputation as a missing link seems unjustified.91

This meant that the only serious claim of a transitional form between fish and amphibians had been demolished.

The claim that fish are the ancestors of land-dwelling creatures is invalidated by anatomical and physiological observations as much as by the fossil record. When we examine the huge anatomical and physiological differences between water- and land-dwelling creatures, we can see that these differences could not have disappeared in an evolutionary process with gradual changes based on chance. We can list the most evident of these differences as follows

1- Weight-bearing: Sea-dwelling creatures have no problem in bearing their own weight in the sea, although the structures of their bodies are not made for such a task on land. However, most land-dwelling creatures consume 40 percent of their energy just in carrying their bodies around. Creatures claimed to make the transition from water to land would at the same time need new muscular and skeletal systems to meet this energy need, and this could not have come about by chance mutations.

The basic reason why evolutionists imagine the coelacanth and similar fish to be the ancestors of land-dwelling creatures is that their fins contain bones. It is assumed that over time these fins turned into load-bearing feet. However, there is a fundamental difference between these fish's bones and land-dwelling creatures' feet. It is impossible for the former to take on a load-bearing function, as they are not linked to the backbone. Land-dwelling creatures' bones, in contrast, are directly connected to the backbone. For this reason, the claim that these fins slowly developed into feet is unfounded.

2- Heat retention: On land, the temperature can change quickly, and fluctuates over a wide range. Land-dwelling creatures possess a physical mechanism that can withstand such great temperature changes. However, in the sea, the temperature changes slowly, and within a narrower range. A living organism with a body system regulated according to the constant temperature of the sea would need to acquire a protective system to ensure minimum harm from the temperature changes on land. It is preposterous to claim that fish acquired such a system by random mutations as soon as they stepped onto land.

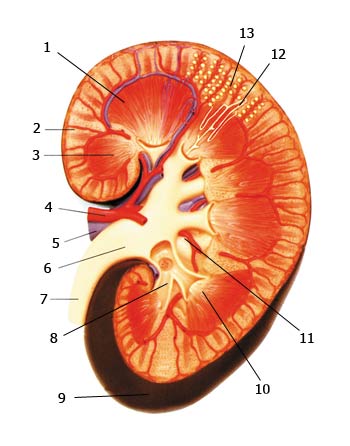

1 - medulla pyramid, 2 - cortex, 3 - medulla, 4 - renal artery, 5 - renal vein, 6 - renal pelvis, 7 -, ureter, 8 - Small glass, 9 - Fibrous capsule, 10 - renal papilla, 11 - Kidney sine, 12 - Nephron, 13 - Bowman's capsule

The Kidney Problem

Fish remove harmful substances from their bodies directly into the water, but land animals need kidneys. For this reason, the scenario of transition from water to the land requires kidneys to have developed by chance. However, kidneys possess an exceedingly complex structure and, what is more, the kidney needs to be 100 percent present and in complete working order in order to function. A kidney developed 50, or 70, or even 90 percent will serve no function. Since the theory of evolution depends on the assumption that "organs that are not used disappear," a 50 percent-developed kidney will disappear from the body in the first stage of evolution.

3- Water: Essential to metabolism, water needs to be used economically due to its relative scarcity on land. For instance, the skin has to be able to permit a certain amount of water loss, while also preventing excessive evaporation. That is why land-dwelling creatures experience thirst, something that sea-dwelling creatures do not do. For this reason, the skin of sea-dwelling animals is not suitable for a nonaquatic habitat.

4- Kidneys: Sea-dwelling organisms discharge waste materials, especially ammonia, by means of their aquatic environment: In freshwater fish, most of the nitrogenous wastes (including large amounts of ammonia, NH3) leave by diffusion out of the gills. The kidney is mostly a device for maintaining water balance in the animal, rather than an organ of excretion. Marine fish have two types. Sharks, skates, and rays may carry very high levels of urea in their blood. Shark's blood may contain 2.5% urea in contrast to the 0.01-0.03% in other vertebrates. The other type, i. e., marine bony fish, are much different. They lose water continuously but replace it by drinking seawater and then desalting it. They rely on excretory systems, which are very different from those of terrestrial vertebrates, for eliminating excess or waste solutes. Therefore, in order for the passage from water to land to have occurred, living things without a kidney would have had to develop a kidney system all at once.

5- Respiratory system: Fish "breathe" by taking in oxygen dissolved in water that they pass through their gills. They cannot live more than a few minutes out of water. In order to survive on land, they would have to acquire a perfect lung system all of a sudden.

It is most certainly impossible that all these dramatic physiological changes could have happened in the same organism at the same time, and all by chance.

Metamorphosis

Frogs are born in water, live there for a while, and finally emerge onto land in a process known as "metamorphosis." Some people think that metamorphosis is evidence of evolution, whereas the two actually have nothing to do with one another.

The sole innovative mechanism proposed by evolution is mutation. However, metamorphosis does not come about by coincidental effects like mutation does. On the contrary, this change is written in frogs' genetic code. In other words, it is already evident when a frog is first born that it will have a type of body that allows it to live on land. Research carried out in recent years has shown that metamorphosis is a complex process governed by different genes. For instance, just the loss of the tail during this process is governed, according to Science News magazine, by more than a dozen genes (Science News, July 17, 1999, page 43).

The evolutionists' claim of transition from water to land says that fish, with a genetic code completely created to allow them to live in water, turned into land creatures as a result of chance mutations. However, for this reason metamorphosis actually tears evolution down, rather than shoring it up, because the slightest error in the process of metamorphosis means the creature will die or be deformed. It is essential that metamorphosis should happen perfectly. It is impossible for such a complex process, which allows no room for error, to have come about by chance mutations, as is claimed by evolution.

Dinosaur, lizard, turtle, crocodile—all these fall under the class of reptiles. Some, such as dinosaurs, are extinct, but the majority of these species still live on the earth. Reptiles possess some distinctive features. For example, their bodies are covered with scales, and they are cold-blooded, meaning they are unable to regulate their body temperatures physiologically (which is why they expose their bodies to sunlight in order to warm up). Most of them reproduce by laying eggs.

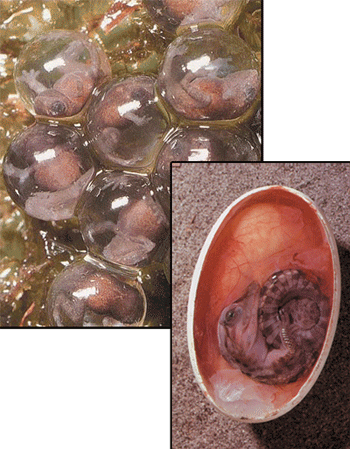

Different Eggs

One of the inconsistencies in the amphibian-reptile evolution scenario is the structure of the eggs. Amphibian eggs, which develop in water, have a jelly-like structure and a porous membrane, whereas reptile eggs, as shown in the reconstruction of a dinosaur egg on the right, are hard and impermeable, in order to conform to conditions on land. In order for an amphibian to become a reptile, its eggs would have to have coincidentally turned into perfect reptile eggs, and yet the slightest error in such a process would lead to the extinction of the species.

Regarding the origin of these creatures, evolution is again at an impasse. Darwinism claims that reptiles evolved from amphibians. However, no discovery to verify such a claim has ever been made. On the contrary, comparisons between amphibians and reptiles reveal that there are huge physiological gaps between the two, and a "half reptile-half amphibian" would have no possibility of survival.

One example of the physiological gaps between these two groups is the different structures of their eggs. Amphibians lay their eggs in water, and their eggs are jelly-like, with a transparent and permeable membrane. Such eggs possess an ideal structure for development in water. Reptiles, on the other hand, lay their eggs on land, and consequently their eggs are created to survive there. The hard shell of the reptile egg, also known as an "amniotic egg," allows air in, but is impermeable to water. In this way, the water needed by the developing animal is kept inside the egg.

If amphibian eggs were laid on land, they would immediately dry out, killing the embryo. This cannot be explained in terms of evolution, which asserts that reptiles evolved gradually from amphibians. That is because, for life to have begun on land, the amphibian egg must have changed into an amniotic one within the lifespan of a single generation. How such a process could have occurred by means of natural selection and mutation—the mechanisms of evolution—is inexplicable. Biologist Michael Denton explains the details of the evolutionist impasse on this matter:

Every textbook of evolution asserts that reptiles evolved from amphibia but none explains how the major distinguishing adaptation of the reptiles, the amniotic egg, came about gradually as a result of a successive accumulation of small changes. The amniotic egg of the reptile is vastly more complex and utterly different to that of an amphibian. There are hardly two eggs in the whole animal kingdom which differ more fundamentally… The origin of the amniotic egg and the amphibian – reptile transition is just another of the major vertebrate divisions for which clearly worked out evolutionary schemes have never been provided. Trying to work out, for example, how the heart and aortic arches of an amphibian could have been gradually converted to the reptilian and mammalian condition raises absolutely horrendous problems.92

Nor does the fossil record provide any evidence to confirm the evolutionist hypothesis regarding the origin of reptiles.

Robert L. Carroll is obliged to accept this. He has written in his classic work, Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, that "The early amniotes are sufficiently distinct from all Paleozoic amphibians that their specific ancestry has not been established."93 In his newer book, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, published in 1997, he admits that "The origin of the modern amphibian orders, (and) the transition between early tetrapods" are "still poorly known" along with the origins of many other major groups.94

The same fact is also acknowledged by Stephen Jay Gould:

No fossil amphibian seems clearly ancestral to the lineage of fully terrestrial vertebrates (reptiles, birds, and mammals).95

The Seymouria Mistake

Evolutionists at one time claimed that the Seymouria fossil on the left was a transitional form between amphibians and reptiles. According to this scenario, Seymouria was "the primitive ancestor of reptiles." However, subsequent fossil discoveries showed that reptiles were living on earth some 30 million years before Seymouria. In the light of this, evolutionists had to put an end to their comments regarding Seymouria.

So far, the most important animal put forward as the "ancestor of reptiles" has been Seymouria, a species of amphibian. However, the fact that Seymouria cannot be a transitional form was revealed by the discovery that reptiles existed on earth some 30 million years before Seymouria first appeared on it. The oldest Seymouria fossils are found in the Lower Permian layer, or 280 million years ago. Yet the oldest known reptile species, Hylonomus and Paleothyris, were found in lower Pennsylvanian layers, making them some 315-330 million years old.96 It is surely implausible, to say the least, that the "ancestor of reptiles" lived much later than the first reptiles.

In brief, contrary to the evolutionist claim that living beings evolved gradually, scientific facts reveal that they appeared on earth suddenly and fully formed.

An approximately 50 million-year-old python fossil of the genus Palaeopython.

Furthermore, there are impassable boundaries between very different orders of reptiles such as snakes, crocodiles, dinosaurs, and lizards. Each one of these different orders appears all of a sudden in the fossil record, and with very different structures. Looking at the structures in these very different groups, evolutionists go on to imagine the evolutionary processes that might have happened. But these hypotheses are not reflected in the fossil record. For instance, one widespread evolutionary assumption is that snakes evolved from lizards which gradually lost their legs. But evolutionists are unable to answer the question of what "advantage" could accrue to a lizard which had gradually begun to lose its legs, and how this creature could be "preferred" by natural selection.

It remains to say that the oldest known snakes in the fossil record have no "intermediate form" characteristics, and are no different from snakes of our own time. The oldest known snake fossil is Dinilysia, found in Upper Cretaceous rocks in South America. Robert Carroll accepts that this creature "shows a fairly advanced stage of evolution of these features [the specialized features of the skull of snakes],"97 in other words that it already possesses all the characteristics of modern snakes.

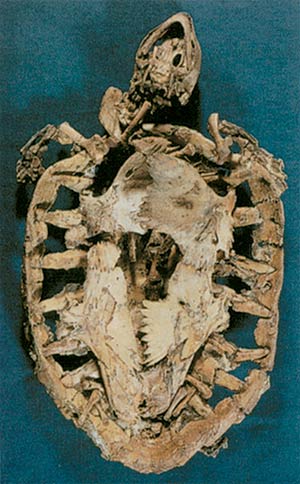

Another order of reptile is turtles, which emerge in the fossil record together with the shells which are so characteristic of them. Evolutionist sources state that "Unfortunately, the origin of this highly successful order is obscured by the lack of early fossils, although turtles leave more and better fossil remains than do other vertebrates. By the middle of the Triassic Period (about 200,000,000 years ago) turtles were numerous and in possession of basic turtle characteristics… Intermediates between turtles and cotylosaurs, reptiles from which turtles [supposedly] sprang, are entirely lacking."98

Thus Robert Carroll is also forced to say that the earliest turtles are encountered in Triassic formations in Germany and that these are easily distinguished from other species by means of their hard shells, which are very similar to those of specimens living today. He then goes on to say that no trace of earlier or more primitive turtles has ever been identified, although turtles fossilize very easily and are easily recognized even if only very small parts are found.99

All these types of living things emerged suddenly and independently. This fact is a scientific proof that they were created.

Above, a freshwater turtle, some 45 million years old, found in Germany. On the right the remains of the oldest known marine turtle. This 110-million-year-old fossil, found in Brazil, is identical to specimens living today.

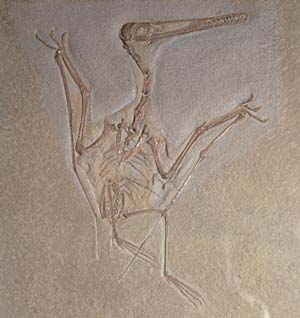

A fossil flying reptile of the species Pterodactylus kochi. This specimen, found in Bavaria, is about 240 million years old.

One interesting group within the reptile class are flying reptiles. These first emerged some 200 million years ago in the Upper Triassic, but subsequently became extinct. These creatures were all reptiles, because they possessed all the fundamental characteristics of the reptile class. They were cold-blooded (i.e., they could not regulate their own internal heat) and their bodies were covered in scales. But they possessed powerful wings, and it is thought that these allowed them to fly.

Flying reptiles are portrayed in some popular evolutionist publications as paleontological discoveries that support Darwinism—at least, that is the impression given. However, the origin of flying reptiles is actually a real problem for the theory of evolution. The clearest indication of this is that flying reptiles emerged suddenly and fully formed, with no intermediate form between them and terrestrial reptiles. Flying reptiles possessed perfectly created wings, which no terrestrial reptile possesses. No half-winged creature has ever been encountered in the fossil record.

In any case, no half-winged creature could have lived, because if these imaginary creatures had existed, they would have been at a grave disadvantage compared to other reptiles, having lost their front legs but being still unable to fly. In that event, according to evolution's own rules, they would have been eliminated and become extinct.

In fact, when flying reptiles' wings are examined, they have such a flawless structure that this could never be accounted for by evolution. Just as other reptiles have five toes on their front feet, flying reptiles have five digits on their wings. But the fourth finger is some 20 times longer than the others, and the wing stretches out under that finger. If terrestrial reptiles had evolved into flying reptiles, then this fourth finger must have grown gradually step by step, as time passed. Not just the fourth finger, but the whole structure of the wing, must have developed with chance mutations, and this whole process would have had to bring some advantage to the creature. Duane T. Gish, one of the foremost critics of the theory of evolution on the paleontological level, makes this comment:

A Eudimorphodon fossil, one of the oldest species of flying reptiles. This specimen, found in northern Italy, is some 220 million years old.

The very notion that a land reptile could have gradually been converted into a flying reptile is absurd. The incipient, part-way evolved structures, rather than conferring advantages to the intermediate stages, would have been a great disadvantage. For example, evolutionists suppose that, strange as it may seem, mutations occurred that affected only the fourth fingers a little bit at a time. Of course, other random mutations occurring concurrently, incredible as it may seem, were responsible for the gradual origin of the wing membrane, flight muscles, tendons, nerves, blood vessels, and other structures necessary to form the wings. At some stage, the developing flying reptile would have had about 25 percent wings. This strange creature would never survive, however. What good are 25 percent wings? Obviously the creature could not fly, and he could no longer run…100

In short, it is impossible to account for the origin of flying reptiles with the mechanisms of Darwinian evolution. And in fact the fossil record reveals that no such evolutionary process took place. Fossil layers contain only land reptiles like those we know today, and perfectly developed flying reptiles. There is no intermediate form. R. Carroll makes the following admission as an evolutionist:

... all the Triassic pterosaurs were highly specialized for flight... They provide little evidence of their specific ancestry and no evidence of earlier stages in the origin of flight.101

Carroll, more recently, in his Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, counts the origin of pterosaurs among the important transitions about which not much is known.102

As can be seen, there is no evidence for the evolution of flying reptiles. Because the term "reptile" means only land-dwelling reptiles for most people, popular evolutionist publications try to give the impression regarding flying reptiles that reptiles grew wings and began to fly. However, the fact is that both land-dwelling and flying reptiles emerged with no evolutionary relationship between them.

The wings of flying reptiles extend along a "fourth finger" some 20 times longer than the other fingers. The important point is that this interesting wing structure emerges suddenly and fully formed in the fossil record. There are no examples indicating that this "fourth finger" grew gradually—in other words, that it evolved.

Another interesting category in the classification of reptiles is marine reptiles. The great majority of these creatures have become extinct, although turtles are an example of one group that survives. As with flying reptiles, the origin of marine reptiles is something that cannot be explained with an evolutionary approach. The most important known marine reptile is the creature known as the ichthyosaur. In their book Evolution of the Vertebrates, Edwin H. Colbert and Michael Morales admit the fact that no evolutionary account of the origin of these creatures can be given:

Fossil ichthyosaur of the genus Stenopterygius, about 250 million years old.

The ichthyosaurs, in many respects the most highly specialized of the marine reptiles, appeared in early Triassic times. Their advent into the geologic history of the reptiles was sudden and dramatic; there are no clues in pre-Triassic sediments as to the possible ancestors of the ichthyosaurs… The basic problem of ichthyosaur relationships is that no conclusive evidence can be found for linking these reptiles with any other reptilian order.103

200-million-year-old ichthyosaur fossil.

Similarly, Alfred S. Romer, another expert on the natural history of vertebrates, writes:

No earlier forms [of ichthyosaurs] are known. The peculiarities of ichthyosaur structure would seemingly require a long time for their development and hence a very early origin for the group, but there are no known Permian reptiles antecedent to them.104

Carroll again has to admit that the origin of ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs (another family of aquatic reptiles) are among the many "poorly known" cases for evolutionists.105

In short, the different creatures that fall under the classification of reptiles came into being on the earth with no evolutionary relationship between them. As we shall see in due course, the same situation applies to mammals: there are flying mammals (bats) and marine mammals (dolphins and whales). However, these different groups are far from being evidence for evolution. Rather, they represent serious difficulties that evolution cannot account for, since in all cases the different taxonomical categories appeared on earth suddenly, with no intermediate forms between them, and with all their different structures already intact.

This is clear scientific proof that all these creatures were actually created.

56 Stephen C. Meyer, P. A. Nelson, and Paul Chien, The Cambrian Explosion: Biology's Big Bang, 2001, p. 2.

57 Richard Monastersky, "Mysteries of the Orient," Discover, April 1993, p. 40. (emphasis added)

58 Richard Monastersky, "Mysteries of the Orient," Discover, April 1993, p. 40.

59 Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker, W. W. Norton, London, 1986, p. 229. (emphasis added)

60 Phillip E. Johnson, "Darwinism's Rules of Reasoning," in Darwinism: Science or Philosophy by Buell Hearn, Foundation for Thought and Ethics, 1994, p. 12. (emphasis added)

61 R. Lewin, Science, vol. 241, 15 July 1988, p. 291. (emphasis added)

62 Gregory A. Wray, "The Grand Scheme of Life," Review of The Crucible Creation: The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals by Simon Conway Morris, Trends in Genetics, February 1999, vol. 15, no. 2.

63 Richard Fortey, "The Cambrian Explosion Exploded?," Science, vol. 293, no. 5529, 20 July 2001, pp. 438-439.

64 Richard Fortey, "The Cambrian Explosion Exploded?," Science, vol. 293, no. 5529, 20 July 2001, pp. 438-439.

65 Douglas J. Futuyma, Science on Trial, Pantheon Books, New York, 1983, p. 197.

66 Jeffrey S. Levinton, "The Big Bang of Animal Evolution," Scientific American, vol. 267, November 1992, p. 84.

67 "The New Animal Phylogeny: Reliability And Implications", Proc. of Nat. Aca. of Sci., 25 April 2000, vol. 97, no. 9, pp. 4453-4456.

68 "The New Animal Phylogeny: Reliability And Implications, Proc. of Nat. Aca. of Sci., 25 April 2000, vol. 97, no. 9, pp. 4453-4456.

69 David Raup, "Conflicts Between Darwin and Paleontology," Bulletin, Field Museum of Natural History, vol. 50, January 1979, p. 24.

70 Richard Fortey, "The Cambrian Explosion Exploded?," Science, vol. 293, no. 5529, 20 July 2001, pp. 438-439.

71 Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, 1859, p. 313-314.

72 Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species: A Facsimile of the First Edition, Harvard University Press, 1964, p. 302.

73 Stefan Bengston, Nature, vol. 345, 1990, p. 765. (emphasis added)

74 R. L. Gregory, Eye and Brain: The Physiology of Seeing, Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 31.

75 Douglas Palmer, The Atlas of the Prehistoric World, Discovery Channel, Marshall Publishing, London, 1999, p. 66.

76 Mustafa Kuru, Omurgal Hayvanlar (Vertebrates), Gazi University Publications, 5th ed., Ankara, 1996, p. 21. (emphasis added)

77 Mustafa Kuru, Omurgal Hayvanlar (Vertebrates), Gazi University Publications, 5th ed., Ankara, 1996, p. 27.

78 Douglas Palmer, The Atlas of the Prehistoric World, Discovery Channel, Marshall Publishing, London, 1999, p. 64.

79 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 296.

80 Gerald T. Todd, "Evolution of the Lung and the Origin of Bony Fishes: A Casual Relationship," American Zoologist, vol. 26, no. 4, 1980, p. 757.

81 Ali Demirsoy, Kaltm ve Evrim (Inheritance and Evolution), Meteksan Publishing Co., Ankara, 1984, pp. 495-496.

82 Henry Gee, In Search Of Deep Time: Going Beyond The Fossil Record To A Revolutionary Understanding of the History Of Life, The Free Press, A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc., 1999, p. 7.

83 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 230.

84 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 301.

85 This time frame is also given by Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 304.

86 Henry Gee, In Search Of Deep Time: Going Beyond The Fossil Record To A Revolutionary Understanding of the History Of Life, The Free Press, A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1999, p. 54.

87 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 292-93.

88 Jean-Jacques Hublin, The Hamlyn Encyclopædia of Prehistoric Animals, The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd., New York, 1984, p. 120.

89 www.ksu.edu/fishecology/relict.htm

90 http://www.cnn.com/TECH/science

/9809/23/living.fossil/index.html

91 P. L. Forey, Nature, vol. 336, 1988, p. 727.

92 Michael Denton, Evolution: A Theory In Crisis, Adler and Adler, 1986, pp. 218-219.

93 Robert L. Carroll, Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, W. H. Freeman and Co., New York, 1988, p. 198.

94 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 296-97.

95 Stephen Jay Gould, "Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies," Natural History, vol. 100, no. 1, January 1991, p. 25. (emphasis added)

96 Duane Gish, Evolution: The Fossils Still Say No!, Institute For Creation Research, California, 1995, p. 97.

97 Robert Carroll, Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, p. 235.

98 Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, "Turtle – Origin and Evolution."

99 Robert L. Carroll, Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, p. 207.

100 Duane T. Gish, Evolution: The Fossils Still Say No, ICR, San Diego, 1998, p. 103.

101 Robert L. Carroll, Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. p. 336. (emphasis added)

102 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 296-97.

103 E. H. Colbert, M. Morales, Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley and Sons, 1991, p. 193. (emphasis added)

104 A. S Romer, Vertebrate Paleontology, 3rd ed., Chicago University Press, Chicago, 1966, p. 120. (emphasis added)

105 Robert L. Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 296-97.