In an earlier chapter, we examined how the fossil record clearly invalidates the hypotheses of the Darwinist theory. We saw that the different living groups in the fossil record emerged suddenly, and stayed fixed for millions of years without undergoing any changes. This great discovery of paleontology shows that living species exist with no evolutionary processes behind them.

This fact was ignored for many years by paleontologists, who kept hoping that imaginary "intermediate forms" would one day be found. In the 1970s, some paleontologists accepted that this was an unfounded hope and that the "gaps" in the fossil record had to be accepted as a reality. However, because these paleontologists were unable to relinquish the theory of evolution, they tried to explain this reality by modifying the theory. And so was born the "punctuated equilibrium" model of evolution, which differs from neo-Darwinism in a number of respects.

This model began to be vigorously promoted at the start of the 1970s by the paleontologists Stephen Jay Gould of Harvard University and Niles Eldredge of the American Museum of Natural History. They summarized the evidence presented by the fossil record as revealing two basic characteristics:

1. Stasis

2. Sudden appearance 173

In order to explain these two facts within the theory of evolution, Gould and Eldredge proposed that living species came about not through a series of small changes, as Darwin had maintained, but by sudden, large ones.

This theory was actually a modified form of the "Hopeful Monster" theory put forward by the German paleontologist Otto Schindewolf in the 1930s. Schindewolf suggested that living things evolved not, as neo-Darwinism had proposed, gradually over time through small mutations, but suddenly through giant ones. When giving examples of his theory, Schindewolf claimed that the first bird in history had emerged from a reptile egg by a huge mutation—in other words, through a giant, coincidental change in genetic structure.174 According to this theory, some land animals might have suddenly turned into giant whales through a comprehensive change that they underwent. This fantastic theory of Schindewolf's was taken up and defended by the Berkeley University geneticist Richard Goldschmidt. But the theory was so inconsistent that it was quickly abandoned.

The factor that obliged Gould and Eldredge to embrace this theory again was, as we have already established, that the fossil record is at odds with the Darwinistic notion of step by step evolution through minor changes. The fact of stasis and sudden emergence in the record was so empirically well supported that they had to resort to a more refined version of the "hopeful monster" theory again to explain the situation. Gould's famous article "Return of the Hopeful Monster" was a statement of this obligatory step back.175

Gould and Eldredge did not just repeat Schindewolf's fantastic theory, of course. In order to give the theory a "scientific" appearance, they tried to develop some kind of mechanism for these sudden evolutionary leaps. (The interesting term, "punctuated equilibrium," they chose for this theory is a sign of this struggle to give it a scientific veneer.) In the years that followed, Gould and Eldredge's theory was taken up and expanded by some other paleontologists. However, the punctuated equilibrium theory of evolution was full of contradictions and inconsistencies at least as much as the neo-Darwinist theory of evolution did.

The punctuated equilibrium theory of evolution, in its present state, holds that living populations show no changes over long periods of time, but stay in a kind of equilibrium. According to this viewpoint, evolutionary changes take place in short time frames and in very restricted populations—that is, the equilibrium is divided into separate periods or, in other words, "punctuated." Because the population is very small, large mutations are chosen by means of natural selection and thus enable a new species to emerge.

For instance, according to this theory, a species of reptile survives for millions of years, undergoing no changes. But one small group of reptiles somehow leaves this species and undergoes a series of major mutations, the reason for which is not made clear. Those mutations which are advantageous quickly take root in this restricted group. The group evolves rapidly, and in a short time turns into another species of reptile, or even a mammal. Because this process happens very quickly, and in a small population, there are very few fossils of intermediate forms left behind, or maybe none.

On close examination, this theory was actually proposed to develop an answer to the question, "How can one imagine an evolutionary period so rapid as not to leave any fossils behind it?" Two basic hypotheses are accepted while developing this answer:

1. that macromutations—wide-ranging mutations leading to large changes in living creatures' genetic make-up—bring advantages and produce new genetic information; and

2. that small animal populations have greater potential for genetic change.

However, both of these hypotheses are clearly at odds with scientific knowledge.

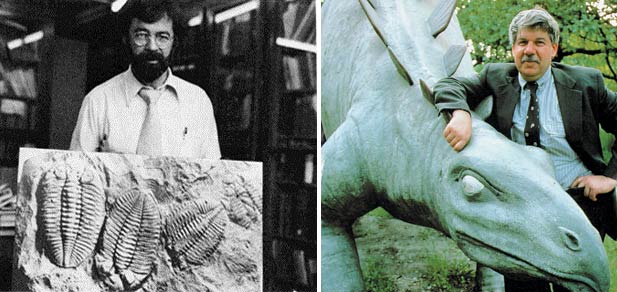

Two famous proponents of the punctuated evolution model: Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge.

The first hypothesis—that macromutations occur in large numbers, making the emergence of new species possible—conflicts with known facts of genetics.

One rule, put forward by R. A. Fisher, one of the last century's best known geneticists, and based on observations, clearly invalidates this hypothesis. Fisher states in his book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection that the likelihood that a particular mutation will become fixed in a population is inversely proportional to its effect on the phenotype.176 Or, to put it another way, the bigger the mutation, the less possibility it has of becoming a permanent trait within the group.

It is not hard to see the reason for this. Mutations, as we have seen in earlier chapters, consist of chance changes in genetic codes, and never have a beneficial influence on organisms' genetic data. Quite the contrary: individuals affected by mutation undergo serious illnesses and deformities. For this reason, the more an individual is affected by mutation, the less possibility it has of surviving.

Ernst Mayr, a fervent advocate of Darwinism, makes this comment on the subject:

The occurrence of genetic monstrosities by mutation … is well substantiated, but they are such evident freaks that these monsters can be designated only as 'hopeless'. They are so utterly unbalanced that they would not have the slightest chance of escaping elimination through stabilizing selection … the more drastically a mutation affects the phenotype, the more likely it is to reduce fitness. To believe that such a drastic mutation would produce a viable new type, capable of occupying a new adaptive zone, is equivalent to believing in miracles … The finding of a suitable mate for the 'hopeless monster' and the establishment of reproductive isolation from the normal members of the parental population seem to me insurmountable difficulties.177

It is obvious that mutations cannot bring about evolutionary development, and this fact places both neo-Darwinism and the punctuated equilibrium theory of evolution in a terrible difficulty. Since mutation is a destructive mechanism, the macromutations that proponents of the punctuated equilibrium theory talk about must have "macro" destructive effects. Some evolutionists place their hopes in mutations in the regulatory genes in DNA. But the feature of destructiveness which applies to other mutations, applies to these, as well. The problem is that mutation is a random change: any kind of random change in a structure as complex as genetic data will lead to harmful results.

In their book The Natural Limits to Biological Change, the geneticist Lane Lester and the population biologist Raymond Bohlin describe the blind alley represented by the notion of macromutation:

The overall factor that has come up again and again is that mutation remains the ultimate source of all genetic variation in any evolutionary model. Being unsatisfied with the prospects of accumulating small point mutations, many are turning to macromutations to explain the origin of evolutionary novelties. Goldschmidt's hopeful monsters have indeed returned. However, though macromutations of many varieties produce drastic changes, the vast majority will be incapable of survival, let alone show the marks of increasing complexity. If structural gene mutations are inadequate because of their inability to produce significant enough changes, then regulatory and developmental mutations appear even less useful because of the greater likelihood of nonadaptive or even destructive consequences… But one thing seems certain: at present, the thesis that mutations, whether great or small, are capable of producing limitless biological change is more an article of faith than fact.178

Observation and experiment both show that mutations do not enhance genetic data, but rather damage living things. Therefore, it is clearly irrational for proponents of the punctuated equilibrium theory to expect greater success from "mutations" than the mainstream neo-Darwinists have found.

Richard Dawkins, busy indoctrinating the young through Darwinist propaganda.

The second concept stressed by the proponents of punctuated equilibrium theory is that of "restricted populations." By this, they mean that the emergence of new species comes about in communities containing very small numbers of plants or animals. According to this claim, large populations of animals show no evolutionary development and maintain their "stasis." But small groups sometimes become separated from these communities, and these "isolated" groups mate only amongst themselves. (It is hypothesized that this usually stems from geographical conditions.) Macromutations are supposed to be most effective within such small, inbreeding groups, and that is how rapid "speciation" can take place.

But why do proponents of the punctuated equilibrium theory insist so much on the concept of restricted populations? The reason is clear: Their aim is try to provide an explanation for the absence of intermediate forms in the fossil record.

However, scientific experiments and observations carried out in recent years have revealed that being in a restricted population is not an advantage for the theory of evolution from the genetic point of view, but rather a disadvantage. Far from developing in such a way as to give rise to new species, small populations give rise to serious genetic defects. The reason for this is that in restricted populations individuals must continually mate within a narrow genetic pool. For this reason, normally heterozygous individuals become increasingly homozygous. This means that defective genes which are normally recessive become dominant, with the result that genetic defects and sickness increase within the population.179

In order to examine this matter, a 35-year study of a small, inbred population of chickens was carried out. It was found that the individual chickens became progressively weaker from the genetic point of view over time. Their egg production fell from 100 to 80 percent of individuals, and their fertility declined from 93 to 74 percent. But when chickens from other regions were added to the population, this trend toward genetic weakening was halted and even reversed. With the infusion of new genes from outside the restricted group, eventually the indicators of the health of the population returned to normal.180

This and similar discoveries have clearly revealed that the claim by the proponents of punctuated equilibrium theory that small populations are the source of evolution has no scientific validity.

Scientific discoveries do not support the claims of the punctuated equilibrium theory of evolution. The claim that organisms in small populations can swiftly evolve with macromutations is actually at least as invalid as the model of evolution proposed by the mainstream neo-Darwinists.

So, why has this theory become so popular in recent years? This question can be answered by looking at the debates within the Darwinist community. Almost all the proponents of the punctuated equilibrium theory of evolution are paleontologists. This group, led by such paleontologists as Stephen Jay Gould, Niles Eldredge, and Steven M. Stanley, clearly see that the fossil record disproves the Darwinist theory. However, they have conditioned themselves to believe in evolution, no matter what. So for this reason they have resorted to the punctuated equilibrium theory as the only way of accounting even in part for the facts of the fossil record.

On the other hand, geneticists, zoologists, and anatomists see that there is no mechanism in nature which can give rise to any "punctuations," and for this reason they insist on defending the gradualistic Darwinist model of evolution. The Oxford University zoologist Richard Dawkins fiercely criticizes the proponents of the punctuated equilibrium model of evolution, and accuses them of "destroying the theory of evolution's credibility."

The result of this dialogue of the deaf is the scientific crisis the theory of evolution now faces. We are dealing with an evolution myth which agrees with no experiments or observations, and no paleontological discoveries. Every evolutionist theoretician tries to find support for the theory from his own field of expertise, but then enters into conflict with discoveries from other branches of science. Some people try to gloss over this confusion with superficial comments such as "science progresses by means of academic disputes of this kind." However, the problem is not that the mental gymnastics in these debates are being carried out in order to discover a correct scientific theory; rather, the problem is that speculations are being advanced dogmatically and irrationally in order to stubbornly defend a theory that is demonstrably false.

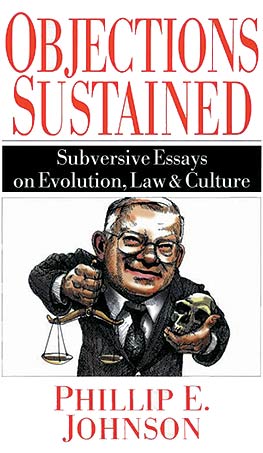

However, the theoreticians of punctuated equilibrium have made one important, albeit unwitting, contribution to science: They have clearly shown that the fossil record conflicts with the concept of evolution. Phillip Johnson, one of the world's foremost critics of the theory of evolution, has described Stephen Jay Gould, one of the most important punctuated equilibrium theoreticians, as "the Gorbachev of Darwinism."181 Gorbachev thought that there were defects in the Communist state system of the Soviet Union and tried to "reform" that system. However, the problems which he thought were defects were in fact fundamental to the nature of the system itself. That is why Communism melted away in his hands.

The same fate awaits Darwinism and the other models of evolution.

173 Stephen Jay Gould, "Evolution's Erratic Pace," Natural History, vol. 86, May 1977, p. 14.

174 Stephen M. Stanley, Macroevolution: Pattern and Process, W. H. Freeman and Co., San Francisco, 1979, pp. 35, 159.

175 S. J. Gould, "Return of the Hopeful Monster," The Panda's Thumb, W. W. Norton Co., New York, 1980, pp. 186-193.

176 R. A. Fisher, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1930.

177 Ernst Mayr, Populations, Species, and Evolution, Belknap Press, Cambridge, 1970, p. 235.

178 Lane P. Lester, Raymond G. Bohlin, The Natural Limits to Biological Change, Probe Books, Dallas, 1989, pp. 141-142. (emphasis added)

179 M. E. Soulé and L. S. Mills, "Enhanced: No need to isolate genetics," Science, 1998, vol. 282, p. 1658.

180 R. L. Westemeier, J. D. Brawn, J. D. Brawn, S. A. Simpson, T. L. Esker, R. W. Jansen, J. W. Walk, E. L. Kershner, J. L. Bouzat, and K. N. Paige, "Tracking the long-term decline and recovery of an isolated population", Science, 1998, vol. 282, p. 1695.

181 Phillip Johnson, Objections Sustained, Intervarsity Press, Illinois, 1998, pp. 77-85.