Creating technology—all the manufacturing methods and equipment used in a particular branch of industry—is no easy matter, because so many components need to be brought together. In order to produce technology in any given area, first of all we need to possess information. Next, the scientists and technical personnel who are to use this information must be added to the equation. These personnel need the right materials and the facilities in which to make use of them. For all these reasons, producing technology is a difficult business. Indeed, the history of those advances we describe as "technological" is by no means a long one. Even today, though many countries enjoy technology, very few of them actually produce it.

As scientific circles have noted, most of the technological products emerging as the result of investment, information and research have their "originals" and counterparts in nature.

Phil Gates, a well-known scientist and author of the book Wild Technology, expresses this in the following terms:

Many of our best inventions are copied from, or already in use by, other living things. We have only discovered a tiny fraction of the vast numbers of living organisms that share our planet. Somewhere, amongst the millions of organisms that remain undiscovered, there are natural inventions that could improve our lives. They could provide new medicines, building materials, ways of controlling pests and dealing with pollution.123

Every niche of our surroundings—from the sky to the land to the depths of the oceans—are full of countless "technological" marvels, each of them a product of creation. Even the simplest industrial product has a designer and place where it was manufactured. That being so, it would be obviously irrational to claim that living things, possessing systems incomparably superior to huge factories with their state-of-the-art machinery, could have arisen through chance, by themselves, as a result of natural conditions.

Every living thing possesses a superior, perfect design that emerged flawless and complete from the very day of its creation, because God is He Who creates flawlessly.

In this chapter we'll examine some marvels of creation and compare them to present-day technology. We should regard these examples as food for thought, as God instructs us in the Qur'an, "An instruction and a reminder for every penitent human being." (Qur'an, 50: 8)

Some species of plants are acutely sensitive to changes in light intensity. When night falls, they close up their petals. Some flowering plants even do this in cloudy weather, in order—scientists believe—to protect their pollen from dew and approaching rain. We humans also use sensors that detect light intensity changes, and use them in lamps that go on when it gets dark at night and turn themselves off at dawn.124

|

| Some flowers, sensitive to light, close their petals when it grows dark and keep them closed until dawn. Others keep their flowers facing the sun throughout the day. |

|

| Above: In a light sensor, the electrical circuit consists of a great many parts. If just one is removed or only one connection altered, the circuit fails to work. The light sensors in plants possess a feature similar to this circuit: The slightest deficiency in the system will make the sensor totally useless. |

Our bodies generate heat energy by digesting the food we've eaten during the day. The best way to prevent the loss of this warmth is to keep it from leaving our bodies too soon. That is why we wear varying layers of clothing, depending on the weather. Warm air, trapped between the layers, is unable to reach outside. Preventing energy loss in this way is known as insulation.

The eider duck employs the exact same method. Like many birds, its feathers enable it to fly and also keep it warm. It uses its soft and fluffy chest feathers in building its nest. This down protects the eggs and the emerging featherless chicks from the cold air. Since the eider's feathers retain warm air, they exemplify the very best form of natural insulation.125

Modern mountain climbers keep their bodies warm by wearing special costumes filled with feathers with high heat-retaining properties, similar to those of eider feathers.

| |

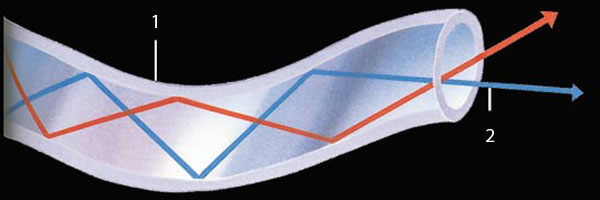

| 1. Optical fiber | 2. Light being reflected down the fiber |

Fiber optics are transparent glass cables capable of transmitting light. Since optical fibers can be easily bent and twisted, they can "pipe" light into even the most inaccessible locations. Fiber optic cables also possess the advantage of being able to carry coded messages loaded onto them, much better than other cables can.

The polar bear's fur is very similar to an optical fiber, carrying the rays of the faint polar sun directly to the animal's body. Since the fur possesses fiber optic capabilities, the sun's rays make direct contact with the bear's skin. So great is its fur's capacity to transmit light that despite the harsh polar climate, the animal's skin turns dark, as if sunburned. The light, converted into heat and absorbed, helps warm the bear's body. Thanks to its fur's unique feature, the bear is able to keep its body warm even under the freezing polar conditions.126

Bears' fur is not their only feature that we can learn from. They can spend up to six months a year in hibernation, doing so by putting their excretory systems on hold and without suffering toxic buildups in their blood. Discovering how they do this will help in the fight against diabetes.127

|  |

| The polar bear isn’t the only living thing possessing fiber optic technology. Leaves of the Fenestraria plant, which lives in the deserts of South Africa, are nearly entirely buried in the sand. This protects Fenestraria from water loss and grazing animals. The tip of every leaf is transparent: Light enters here and can travel down the leaf. (Phil Gates, Wild Technology, 67.) | |

In the coldest climates, local birds generally have their feet either in cold water or standing on ice. Yet there is no question of them ever freezing. All of them possess circulatory systems that reduce heat loss to a minimum. In these birds, heated and chilled blood circulate in different blood vessels, but these vessels run close together, however. In this way, warm blood flowing to the extremities downwards warms the cold blood circulating upwards. This also reduces the shock of cold blood returning to the body from the feet. This natural heat exchange mechanism, known as counter-current, is the same as that used in various machines.128

In these counter-current heat exchangers, as engineers refer them, two fluids (liquid or gas) flow in opposite directions in two separate but contiguous channels. If the fluid in one channel is warmer than in the other, heat passes from the warm fluid to the colder one.

|  |

|  | |

| K1. Key 1 | K2.Key 2 | |

The carnivorous Venus flytrap catches insects that land on its hinged trap and trigger the hairs on it. These hairs act like electrical switches. The instant one is touched, it gives off electrical signals that change the water balance in the plant's cells, and trigger the flow of water out of cells along the leaf midrib, closing the trap.129

The switches controlling the flow of current in electrical circuits operate in much the same way. When the switch is turned off, electric current cannot flow. As soon as it is turned on and the circuit is completed, however, electric current begins to flow along the wire once again. Similarly, animals and plants use a great many biological switches to initiate or halt the flow of electrical signals to the relevant parts of their bodies.130

|  |

|

1. Switch off, circuit incomplete |

The Venus flytrap's circuit actually works like two electrical switches connected together in series. Two hairs must be stimulated before the trap to close.131 This precaution prevents unnecessary closing triggered by such phenomena as raindrops.

Of course, the Venus flytrap knows nothing about electric current or the switches that let these currents flow. Nor is it possible for the plant to receive any kind of training in these areas. That being so, how does it come by this knowledge, which even a human being can't learn without special instruction, and how is it able to employ it so flawlessly? God, the Ruler of all, teaches the plants what to do. The Venus flytrap acts under His inspiration.

|

The snail's drilling system is even able to rasp holes in rocks.The snail’s tongue, called a radula, resembles a large-toothed file. Thanks to this design, the mollusk is able to rasp holes in leaves and pick up algae on rocks. Teeth on the radula are so hard that some desert snails are even able to make holes in rock. (Phil Gates, Wild Technology, 45.) The giant excavators humans use to dig tunnels perform a similar function to the radula. However, the tips of these machines’ drills wear out and have to be frequently replaced. |

Nerve fibers carry messages from the brain to the muscles and other organs, and from there, messages back to the brain. The fibers are coated with a special, fatty substance known as myelin that works just like the plastic insulation around an electric cable. Were it not present, then the electrical signals would leak away into the surrounding tissues, either garbling the message or damaging the body.132

Electric cables are designed to protect from injury those who touch them and also to avoid any loss of power due to electricity leakage. Tough and durable plastics are used for this purpose.

| |

| 1. Nerve Cell | 3. Insulator |

Many animals build underground shelters that require special features to defend them from predators.

In such shelters, the tunnels need to be at a specific distance from the surface and parallel to the ground, or else they may easily be flooded. If the tunnels are dug at a sharp angle, that poses a risk of collapse. Another problem in tunnel construction is meeting the need for air and ventilation.

Prairie dogs are social animals, living in large groups in burrows they construct underground. As their population grows, they dig new burrows, joining them up with tunnels. The space that such complexes occupy can sometimes equal the size of a small city, and thus ventilation assumes a vital importance. Therefore prairie dogs build aboveground towers where their tunnels emerge, rather like volcanoes, which let air be drawn into the city below.

Air travels from regions of high pressure to areas of low. Some of the towers that prairie dogs build are taller than others. Their differences in height give rise to different levels of air pressure in the tunnel entrances. This way, air enters towers with low air pressure above them and emerges through ones with high pressure. Air drawn into the tunnels passes through all the nests, thus establishing an ideal air circulation system.133

To construct a ventilation system such as employed in prairie dogs' tunnels, knowledge of tunnel building, of high and low air pressure, and how they change with altitude are all essential. All these considerations require consciousness, and all these activities indicate the presence of reason and judgment. Therefore, we need to examine the source of this intelligence in the prairie dogs, since clearly it does not belong to the animals themselves—and, contrary to what evolutionists claim, cannot have resulted from blind chance.

|

|

God, Who provides countless examples in nature for mankind to ponder upon, created prairie dogs, like all living things on Earth. Every rational person needs to think, listen to the voice of his conscience and turn to God whenever he encounters an example of beauty; because God is the All-forgiving, the Lord of infinite justice. In the Qur'an, God gives glad tidings to servants who believe in Him:

Your Lord knows best what is in your selves. If you are righteous,

He is Ever-Forgiving to the remorseful.

(Qur'an, 17: 25)

| |

| 1. Ventilation Channels | 3. Underground Tunnel |

A series of chemical processes turn logs of wood into a kind of pulp that can later be made into paper. However, the natural inventors of paper are actually wasps.

To build their nests, wasps use paper that they make by mixing their saliva with shreds of chewed wood. Our furniture industry makes chipboard in exactly the same way, although using glue instead of saliva.134

|

| This diagram shows the various processes in paper manufacturing. If just one of these stages were skipped, no paper could be produced. The equivalent to all these processes is carried out in the tiny body of the wasp, just a few centimeters long. |

Any wasp resembles a particularly efficient tree-processing and paper making factory. However, all of the processes carried out by large industrial complexes, wasps perform within their own tiny bodies. The paper industry still has a lot to learn from wasps!

|

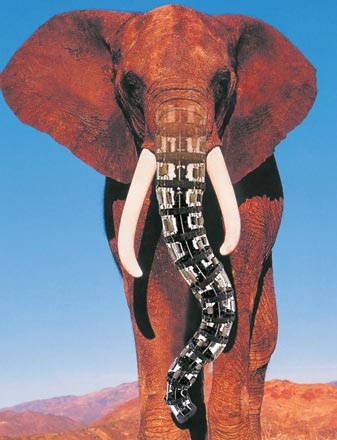

As scientists tried to design a robotic arm, one of the worst problems they faced was achieving freedom of movement. In order for a robot's arm to serve any useful purpose, it must be able to perform all the movements required by that particular task. In nature, God has created all creatures with the ability to move their limbs in such a way as to meet all their needs. An elephant's trunk, with its 50,000 or so muscles,135 is one of the most striking examples.

The elephant is able to move its trunk in any direction it wants and can perform tasks requiring the greatest care and sensitivity.

One robotic arm constructed in the U.S. at Rice University clearly reveals the elephant trunk's superior design. There is no single skeleton-like structure in the trunk, thus endowing it with enormous flexibility and lightness. The robotic arm, on the other hand, does have a spine. The elephant's trunk possesses a degree of movement which allows it to move in any direction, while the robotic arm is comprised of 32 degrees of freedom in 16 links.136

This only goes to show that the elephant trunk is a special structure, whose every particular feature reveals the nature of God's flawless art in creation.

|  |  | |

| a. Base | c. Elbow | e Yaw | g. Roll |

| A robotic arm with six degrees of freedom. Above: A robotic trunk, modeled on the elephant’s, has 32 degrees of freedom. Elephants’ trunks have incomparably greater abilities and freedom of movement. If they had to use these artificial trunks instead of their own, they’d encounter severe difficulties. | |||

123 Phil Gates, Wild Technology, p. 5.

124 Ibid., p. 55.

125 Ibid., p. 64.

126 Ibid., p. 67.

127 "Biomimicry", Your Planet Earth Glossary 1.0.1; http://www.yourplanetearth.org/terms/details.php3?term=Biomimicry

128 Phil Gates, Wild Technology, p. 65.

129 For further information see Harun Yahya's For Men of Understanding, Ta Ha Publishers, April 2003.

130 Phil Gates, Wild Technology, p. 66.

131 http://www.bitkidunyasi.net/ilgincbitkiler/ilgincbitkiler1.html

132 Phil Gates, Wild Technology, p. 67.

133 Animal Inventors, National Geographic Channel (Turkey), November 25, 2001.

134 Phil Gates, Wild Technology, p. 16.

135 Richard Dawkins, Climbing Mount Improbable, W.W. Norton & Company, September 1996, p. 92.

136 "The Elephant's Trunk Robotic Arm;" http://ece.clemson.edu/crb/labs/biomimetic/elephant.htm