|

Two drawings of Java Man, which are totally different from each other, provide a good example of how fantastically fossils are interpreted by evolutionists. |

Before going into the details of the myth of human evolution, we need to mention the propaganda method that has convinced the general public of the idea that half-man half-ape creatures once lived in the past. This propaganda method makes use of "reconstructions" made in reference to fossils. Reconstruction can be explained as drawing a picture or constructing a model of a living thing based on a single bone-sometimes only a fragment-that has been unearthed. The "ape-men" we see in newspapers, magazines, or films are all reconstructions.

The fossils that are claimed to be evidence for the human evolution scenario are in fact products of fraud. For more than 150 years, not even a single fossil to prove evolution has been found. As a matter of fact, the reconstructions (drawings or models) of the fossil remains made by the evolutionists are prepared speculatively precisely to validate the evolutionary thesis. David R. Pilbeam, an anthropologist from Harvard, stresses this fact when he says: "At least in paleoanthropology, data are still so sparse that theory heavily influences interpretations. Theories have, in the past, clearly reflected our current ideologies instead of the actual data".63Since people are highly affected by visual information, these reconstructions best serve the purpose of evolutionists, which is to convince people that these reconstructed creatures really existed in the past.

At this point, we have to highlight one particular point: Reconstructions based on bone remains can only reveal the most general characteristics of the creature, since the really distinctive morphological features of any animal are soft tissues which quickly vanish after death. Therefore, due to the speculative nature of the interpretation of the soft tissues, the reconstructed drawings or models become totally dependent on the imagination of the person producing them. Earnest A. Hooten from Harvard University explains the situation like this:

To attempt to restore the soft parts is an even more hazardous undertaking. The lips, the eyes, the ears, and the nasal tip leave no clues on the underlying bony parts. You can with equal facility model on a Neanderthaloid skull the features of a chimpanzee or the lineaments of a philosopher. These alleged restorations of ancient types of man have very little if any scientific value and are likely only to mislead the public… So put not your trust in reconstructions.64

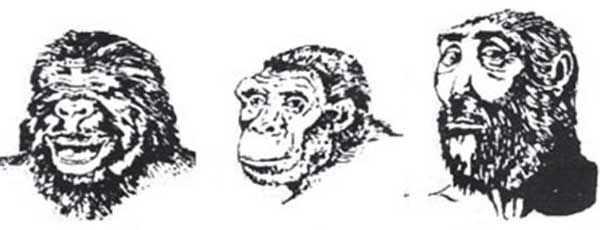

Three Different Reconstructions Based on The Same Skull | ||

| ||

Appeared in Sunday | Maurice Wilson's drawing | N.Parker's reconstruction, |

As a matter of fact, evolutionists invent such "preposterous stories" that they even ascribe different faces to the same skull. For example, the three different reconstructed drawings made for the fossil named Australopithecus robustus (Zinjanthropus), are a famous example of such forgery.

The biased interpretation of fossils and outright fabrication of many imaginary reconstructions are an indication of how frequently evolutionists have recourse to tricks. Yet these seem innocent when compared to the deliberate forgeries that have been perpetrated in the history of evolution.

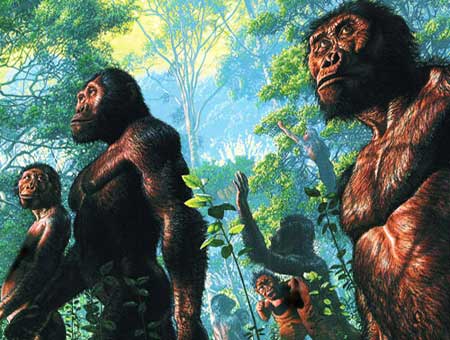

Imaginary Drawing | |

|   |

| |

Geheimnisse Der Urzeit, Tiereund Menschen, s. 200 | |

National Geographic, March 1996 | |

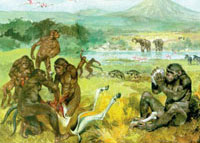

In pictures and reconstructions, evolutionists deliberately give shape to features that do not actually leave any fossil traces, such as the structure of the nose and lips, the shape of the hair, the form of the eyebrows, and other bodily hair so as to support evolution. They also prepare detailed pictures depicting these imaginary creatures walking with their families, hunting, or in other instances of their daily lives. However, these drawings are all figments of the imagination and have no counterpart in the fossil record. | |

63. David Pilbeam, "Rearranging Our Family Tree", Nature, Haziran 1978, s. 40![]()

64. Earnest A. Hooton, Up From The Ape, New York: McMillan, 1931, s. 332![]()