Introduction

A fossil is the name given to the remains or traces of a plant or animal preserved in geologic strata since prehistoric times—or in some cases, remains preserved encased in amber. Fossils collected from all over the world are one of our most important sources of information about the organisms that have existed on Earth since the very earliest times, even hundreds of millions of years ago. Research into fossils enables us to learn about extinct plants and animals, as well as earlier forms of species still in existence today. Thanks to this information, we learn which life forms existed at what epochs in time, what these life forms' features were, and whether they resembled present-day species.

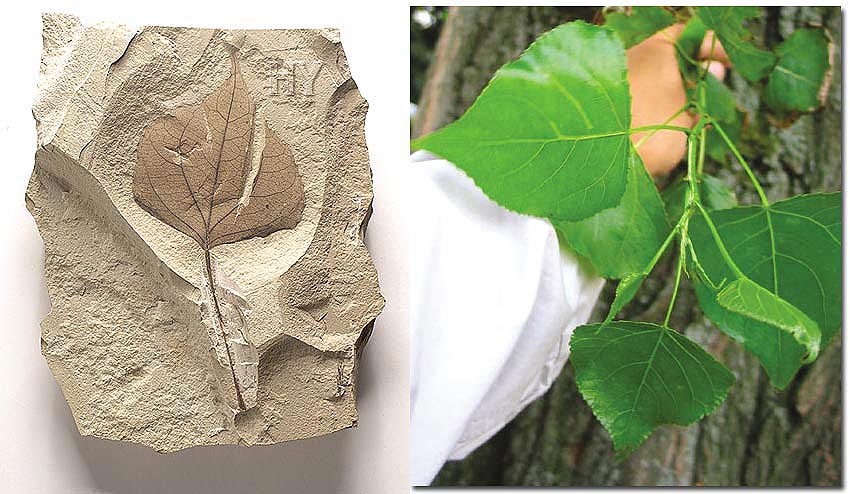

|

| There is no difference between this 54- to 37million-year-old fossilized plane tree leaf and leaves of the same species alive today. |

According to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution—whose scientific invalidity has been revealed by subsequent scientific discoveries—all living things are descended from one single common ancestor. Darwin and his followers claimed that very different life forms developed from one another as the result of small changes over long periods of time.

According to the theory's unsupported claims, random coincidences gave rise to the first living cells. Subsequently, those cells that had formed by chance combined together and over the course of millions of years, became marine invertebrates. Later still, they developed spinal cords and became fish. These fish subsequently emerged onto dry land and gave rise to reptiles, from which birds and mammals then supposedly evolved separately.

If this claim were true, then a great many "intermediate" forms showing the transition between different species should have once existed—and at least a few should have been fossilized. For example, if reptiles really had evolved into birds, then literally billions of half-bird, half-reptile creatures must once have existed. Similarly, there should have been large numbers of life forms that were part invertebrate and part fish, and half-fish, half-reptile. And these intermediate life forms must have had incomplete, partly-developed organs and structures. In addition, if such transitional species had really existed, then their numbers must have run into the hundreds of millions, or even billions, and their fossilized remains should be found all over the world.

|

| Charles Darwin |

Darwin referred to these conjectural creatures as "intermediate forms." He knew perfectly well that if his theory were to be proven, it was absolutely vital that the remains of at least a few of these intermediate forms be discovered. He explained why there must have been a large number of intermediate forms:

By the theory of natural selection all living species have been connected with the parent-species of each genus, by differences not greater than we see between the natural and domestic varieties of the same species at the present day...1

Here, Darwin is saying that the differences between any "ancestor" and the "descendant" during the supposed process of evolution should be as small as the differences in the varieties of any particular living species (between a pedigreed spaniel and a mongrel, for instance). Therefore, if evolution had really taken place as Darwin claimed, it must have done so by way of very small, gradual changes.

Changes in any living thing subjected to mutation will be relatively small. In order for major changes to take place—such as forelegs developing into wings, gills into lungs, or fins into feet—millions of very small successive changes must have accumulated, again over millions of years. This process would necessarily give rise to millions of transitional intermediate forms.

Following his statement quoted above, Darwin arrived at this conclusion:

… the number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great.2

|

| The distinguishing feature of these fossil crabs discovered in Denmark is that they are discovered in round concretions that rise to the surface of the ground at specific times of the year. These fossils, consequently known as "crab balls," generally date back to the Oligocene Period (37 to 23 million years ago). |

|

| This 50-million-year-old fossilized bowfin is proof that these fish, still alive today, have remained unchanged for tens of millions of years. |

| Excavations Over The Last 150 Years have Unearthed Not a Single Intermediate-Form Fossil |

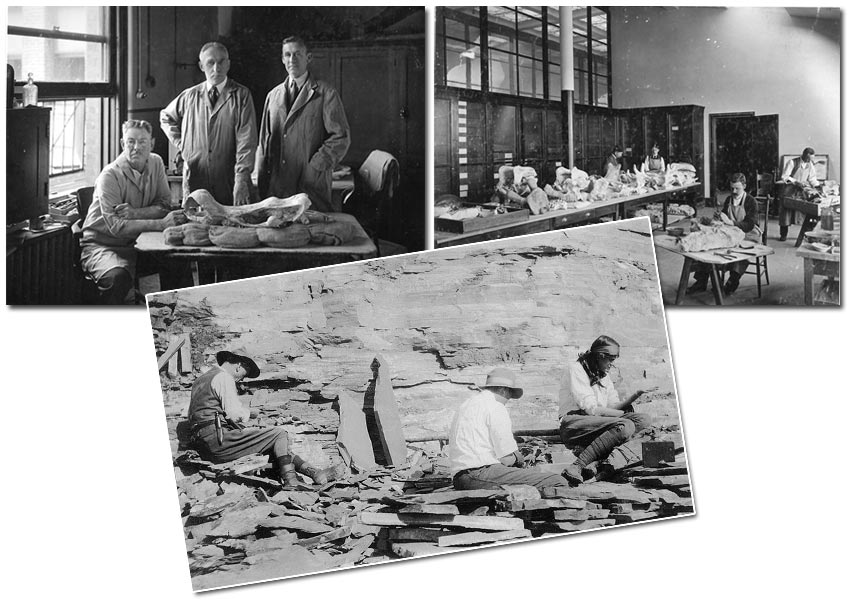

|

| Charles Doolittle Walcott collected some 65,000 specimens of the oldest complex life forms from the Burgess Shale region—and then perpetrated one of the worst scientific frauds of all time. The fossils he found, belonging to life forms from the Cambrian Period (543-490 million years), constituted major evidence that would totally refute the theory of evolution, he concealed them for 70 years in the Smithsonian Museum, of which he was the director at the time. The fact that not a single intermediate-form fossil has ever been unearthed in 150 years of excavations forced Darwinists to perpetrate various frauds. |

Darwin expressed the same point in other parts of his book On the Origin of Species:

If my theory be true, numberless intermediate varieties, linking most closely all of the species of the same group together must assuredly have existed... Consequently evidence of their former existence could be found only amongst fossil remains.3

However, Darwin was well aware that no fossils of these intermediate forms had yet been found. He regarded this as a major difficulty for his theory. In one chapter of his book titled "Difficulties on Theory," he wrote:

Why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?… But, as by this theory innumerable transitional forms must have existed, why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth?… Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory.4

Darwin's only explanation for this major dilemma was lack of evidence—insufficient fossil remains had been discovered at that time. He maintained that later, when the fossil record was examined in detail, the missing intermediate links would inevitably be found. Over the last 150 years, however, research has shown that the hopes of Darwin and his successors were all empty: Not a single intermediate form fossil has ever been encountered.

There are now roughly 100 million fossils in thousands of museums and collections all over the world. All of them are identifiable as species with their own unique structures, distinguished from one another by major anatomical differences. No fossil remains of any half-fish, half-amphibian, or half-dinosaur, half-bird, or half-ape, half-human—forms so eagerly awaited by evolutionists—have ever been discovered.

The paleontologist Niles Eldredge and the anthropologist Ian Tattersall, both from the American Museum of Natural History, state that the fossil record is perfectly adequate in order to understand the history of life—, and that this record in no way supports the theory of evolution:

That individual kinds of fossils remain recognizably the same throughout the length of their occurrence in the fossil record had been known to paleontologists long before Darwin published his Origin. Darwin himself, ... prophesied that future generations of paleontologists would fill in these gaps by diligent search ... One hundred and twenty years of paleontological research later, it has become abundantly clear that the fossil record will not confirm this part of Darwin's predictions. Nor is the problem a miserably poor record. The fossil record simply shows that this prediction is wrong.5

As these evolutionist scientists make clear, it is quite possible to see the true history of life in the fossil record—but there are no intermediate forms in that history.

Other scientists agree that no intermediate forms exist. For example, Rudolf A. Raff, director of the Indiana University Molecular Biology Institute, and the Indiana University researcher Thomas C. Kaufman have declared:

The lack of ancestral or intermediate forms between fossil species is not a bizarre peculiarity of early metazoan history. Gaps are general and prevalent throughout the fossil record.6

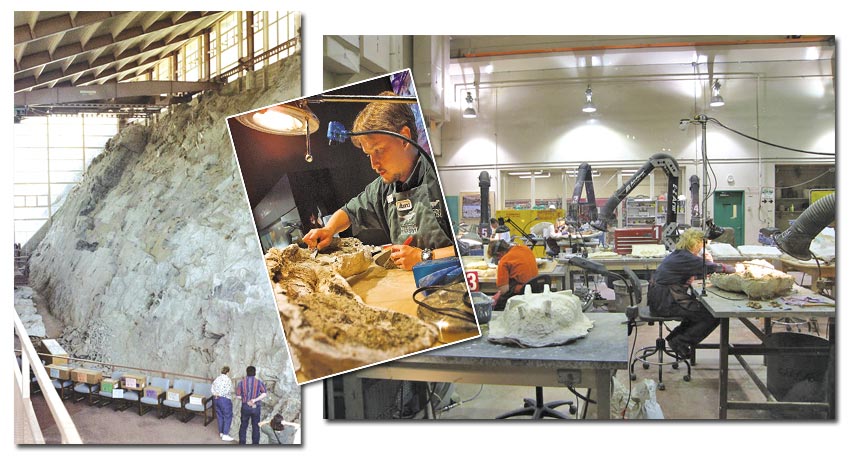

|

| New specimens of fossils are constantly being unearthed all over the world. The number of fossils so far discovered exceeds 100 million. Scientific institutions and academies examine these fossils in detail. Yet as a result of all these endeavors, not a single intermediate life form that might represent evidence for evolution has ever been found. |

The fossil record has even preserved the microscopic remains of bacteria that lived billions of years ago. Yet despite this, not a single fossil belonging to any of these fictitious transitional life forms have ever been found. There are fossils belonging to thousands of different life forms, from ants to bacteria, and from birds to flowering plants. Fossils belonging to extinct plants and animals have been preserved so perfectly that we can establish the structures of extinct life forms that we never see alive today. The absence of even one single intermediate-form specimen, despite the fossil record being so rich, does not indicate that the fossil record is lacking. Rather, it shows the invalidity of the theory of evolution.

Footnotes:

1. C. Darwin, The Origin Of Species, Chapter X, "On the Imperfection of the Geological Record."

2. C. Darwin, The Origin of Species, Chapter X, p. 234.

3. C. Darwin, The Origin of Species, Chapter I, p. 179.

4. C. Darwin, The Origin of Species, Chapter I, p. 172.

5. N. Eldredge and I. Tattersall, The Myths of Human Evolution, Columbia University Press, 1982, pp. 45-46.

6. R. A. Raff and T. C. Kaufman, Embryos, Genes and Evolution: The Developmental Genetic Basis of Evolutionary Change, Indiana University Press, 1991, p. 34.

- Introduction

- Evolutionists' Intermediate-Form Dilemma

- Cambrian Fossils and The Creation of Species

- "Missing Link Discovered" Headlines are an Unscientific Deception

- Darwin's Illogical And Unscientific Formula

- Fossil Specimens of Land Animals (1/2)

- Fossil Specimens of Land Animals (2/2)

- Fossil Specimens of Marine Creatures (1/5)

- Fossil Specimens of Marine Creatures (2/5)

- Fossil Specimens of Marine Creatures (3/5)

- Fossil Specimens of Marine Creatures (4/5)

- Fossil Specimens of Marine Creatures (5/5)

- Fosil Specimens of Plants (1/2)

- Fosil Specimens of Plants (2/2)

- Fossil Specimens of Insects (1/2)

- Fossil Specimens of Insects (2/2)