The countless mosquito fossils discovered to date show that these animals have always been mosquitoes, that they did not evolve from any other life form, and that they never underwent any intermediate stages.

Fossil Specimens Of Birds

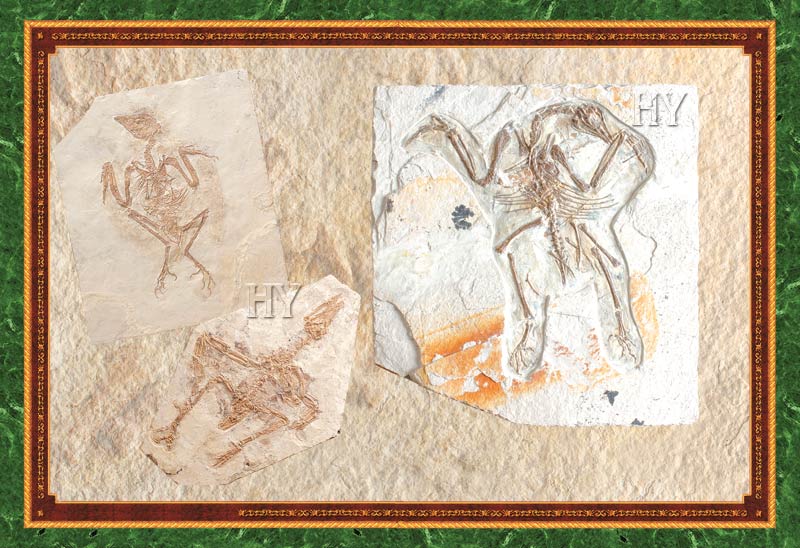

CONFUCIUSORNIS

Age: 120 million years

Period: Mesozoic Age, Cretaceous

Location: Liaoning Province, China

The theory of evolution claims that birds evolved from small therapod dinosaurs—in other words, from reptiles. The fact is, however, that anatomical comparisons between birds and reptiles refute this claim, as does the fossil record.

The fossil pictured belongs to an extinct species of bird known as Confuciusornis, the first specimen of which was discovered in China in 1995. Confuciusornis bears a very close resemblance to present-day birds and has demolished the scenario of bird evolution that evolutionists have proposed for decades.

In describing the imaginary evolution of birds, evolutionists for years used the bird known as Archæopteryx as evidence. All the subsequent scientific findings made, however, show this claim to be untrue. The Conficiusornis fossil is another piece of evidence showing that Archæopteryx cannot be the supposed forerunner of birds.

This bird, from the same period as Archæopteryx (around 140 million years ago), has no teeth. Its beak and feathers have the same characteristics as those of present-day birds. Its skeletal structure is also identical to that of modern-day birds, and it has talons on its wings, as does Archæopteryx. The structure known as the pygostyle, which supports the tail feathers, is also present in this bird. In short, this creature, the same age as Archæopteryx—which evolutionists regard as the oldest supposed forebear of birds, as being half-reptile and half-bird—bears a very close resemblance to modern-day birds. This fact refutes evolutionist theses to the effect that Archæopteryx is the primitive forerunner of all birds.

MESSEL BIRD

Messelornis cristata

Age: 50 million years

Period: Eocene

Location: Messel Shales, Germany

The bird fossil was named for having been discovered in the famous Messel shales. None of the bodily mechanisms of birds, which have a completely different structure from terrestrial life forms, can be explained in terms of any gradual evolutionary model. First of all, wings—the most important feature that makes birds what they are—represent a complete impasse for the theory of evolution. Evolutionists themselves state the impossibility of a reptile being able to fly and indeed, that this claim is contradicted by the fossil record. The ornithologist Alan Feduccia, for example, asks, "How do you derive birds from a heavy, earthbound, bipedal reptile that has a deep body, a heavy balancing tail, and fore-shortened forelimbs? Biophysically, it's impossible." ("Jurassic Bird Challenges Origin Theories," Geotimes, January 1996, p. 7.)

The fossilization of birds is generally a very rare and difficult process because of the hollow structure of their bones. Bird fossils that are very well-preserved with all their limbs are frequently encountered, however, in the Messel Formation in Germany. Messelornis cristata, shown here, is one of the species most frequently discovered. This bird, resembling a small crane in size, is generally included as part of the crane family. It has short feathers, long legs and short nails. Its tail feathers, on the other hand, are quite long. The crest on its head resembles a helmet. The total length of the skeleton is 25 to 30 centimeters (9.8 to 11.8 in).

Some of the fossils belonging to different bird species obtained from the Messel Formation include:

- Aenigmavis

- Messelornis

- Palaeotis (a kind of ostrich)

- Parargornis (a kind of flycatcher)

- Selmes

- Woodpecker

- Hawk

- Flamingo

LIAOXIORNIS

Age: 144-65 million years

Period: Mesozoic Age, Cretaceous

Location: Liaoning Province, China

All the fossils unearthed show that birds have always existed as birds, and that they have not evolved from any other life form. Darwinists, who maintain that birds evolved from terrestrial animals, are actually well aware of this, and are unable to account for how wings and the flight mechanism emerged through an evolutionary process and through random mechanisms such as mutation.

The Turkish biologist Engin Korur admits the impossibility of wing evolution: "The common feature of eyes and wings is that they can perform their functions only when they are fully developed. To put it another way, sight is impossible with a deficient eye, and flight is impossible with half a wing. How these organs appeared is still one of those secrets of nature that have not yet been fully illuminated." (Engin Korur, "Gozlerin ve Kanatlarin Sirri" ("The Secret of Eyes and Wings"), Bilim ve Teknik, No. 203, October 1984, p. 25.)

Powerful wing muscles must be securely attached to the bird's breastbone, and have a structure suitable for lifting the bird into the air and establishing balance and movement in all directions when aloft. It is also essential that bird's wing and tail feathers be light, flexible and in proportion to one another—that they should have a perfect aerodynamic framework making flight possible.

At this point, the theory of evolution faces a major dilemma: The question of how this wing's flawless structure could have emerged as the result of a succession of random mutations goes unanswered. "Evolution" can never explain how a reptile's forelegs could have developed into a flawless wing as the result of impairments in its genes—that is, mutations.

As the quotation cited on the preceding page states, flight is impossible with just a half wing. Therefore, even if we assume that a mutation of some kind did cause some kind of changes in a reptile's forelegs, it is still irrational to expect that a wing could emerge by chance, as a result of other mutations being added on. Any mutation in the front legs would not endow the animal with wings, but would deprive it of the use of its forelegs. This would leave the creature physically disadvantaged (crippled, in other words) compared to other members of its species.

According to biophysical research, mutations take place only very rarely. Therefore, it is impossible to expect such handicapped creatures to wait for millions of years for their half-formed, functionless wings to be completed by small mutations.

CONFUCIUSORNIS SANCTUS

Age: 120 million years

Period: Mesozoic Age, Cretaceous

Location: Liaoning Province, China

The French scientific journal Science et Vie made the following comment regarding this bird, now known as Confuciusornis sanctus: "According to Chinese and American palaeontologists examining the fossil . . . they were dealing with a first class discovery. This flying bird, the same approximate size as a water rail, is around 157 million years old . . . older than Archæopteryx." (Jean Philippe Noel, "Les Oiseaux de la Discorde," Science et Vie, No. 961, October 1997, p. 83.)

The significance of this discovery is obvious; the fact that Confuciusornis lived during the same period as a life form claimed to have been the supposed forerunner of birds—and the fact that it bears a very close similarity to present-day birds—totally invalidates evolutionists' claims.

There are several structural differences between birds and reptiles, one of the most important of these being bone structure. The bones of dinosaurs—regarded by evolutionists as the supposed ancestors of birds—are thick and solid, making them very heavy. On the other hand, the bones of birds—both living and extinct species—are all hollow and thus very light, which is of great importance in their being able to fly.

Another difference between birds and reptiles is their different metabolic rates. Reptiles have one of the slowest metabolisms of all life forms on Earth, while birds hold the highest. Due to a sparrow's very fast metabolism, for example, its body temperature may sometimes rise to as high as 48°C (118.4 F). Reptiles are unable to generate their own body heat, warming their bodies by basking in the sun's rays. Reptiles consume energy the slowest, while birds consume it the highest of all.

Despite his being an evolutionist, Alan Feduccia strongly opposes the theory that birds and dinosaurs are related, on the basis of scientific findings. On the subject of the dino-bird evolution thesis, he has this to say:

Well, I've studied bird skulls for 25 years and I don't see any similarities whatsoever. I just don't see it . . . The theropod origins of birds, in my opinion, will be the greatest embarrassment of paleontology of the 20th century. (Pat Shipman, "Birds Do It … Did Dinosaurs?," New Scientist, 1 February 1997, p. 28.)

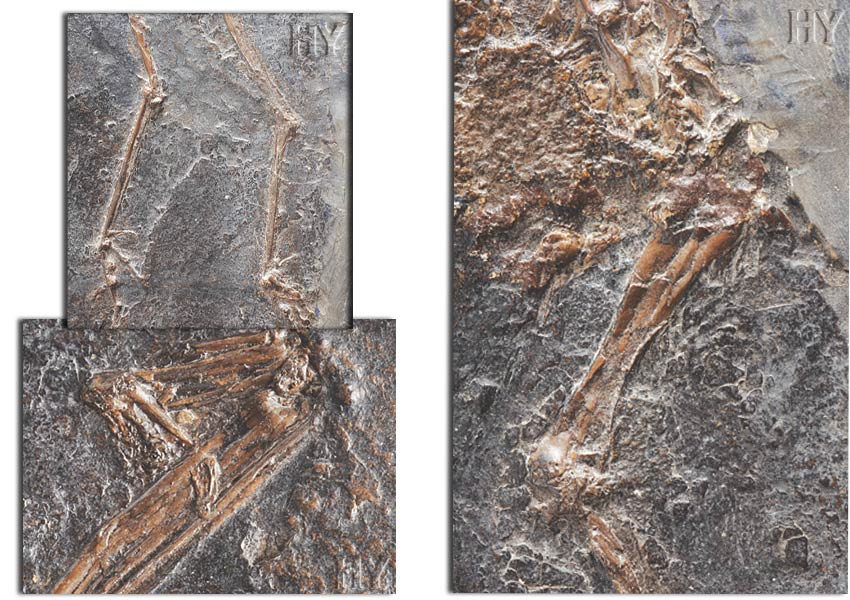

LIAONINGORNIS

Age: 140 million years

Period: Mesozoic Age, Cretaceous

Location: Liaoning Province, China

Yet another discovery that invalidates evolutionist claims regarding the origin of birds is the Liaoningornis fossil shown here. The existence of this bird, around 140 million years of age and first discovered in China in November 1996, was announced by the ornithologists Lianhin Hou, and Martin and Alan Feduccia in an article published in Science magazine.

Liaoningornis had a breastbone to which the flight muscles were attached, as in present-day birds. It was also identical to birds living today in all other respects. The sole difference was that it had teeth in its jaw. This showed that odontornithes (toothed birds) by no means had the kind of primitive structure claimed by evolutionists. Indeed, in an analysis in Discover magazine Alan Feduccia stated that Liaoningornis invalidated the claim that dinosaurs constitute the origin of birds. ("Old Bird," Discover, 21 March 1997.)

One of evolutionists' most unbelievable claims is the thesis they propose to account for how terrestrial animals supposedly began to fly. According to this tale, one that even primary school children would find ridiculous, the forearms of reptiles that hunted flies eventually turned into wings, and the animals began flying. This thesis, a complete misery of logic, is just one of the countless examples of the desperate straits in which Darwinism finds itself. So great is the logical collapse Darwinists exhibited that they never even consider the question of "How were the flies the reptiles were chasing able to fly?"

One of the main features of the fossil record is that living things remain unchanged over the course of very lengthy periods of geological time. There is no difference between this 50-million-year-old fossil fly and specimens alive today.

Specimens of winged insects are frequently encountered in the fossil record, some of which are 300 million years old. The fossil march fly in the picture is 50 million years old.

According To The Evolutionist Dream—Or Rather, Nightmare—, This Should Be The Case

Believing in Darwinist claims regarding the origin of flight means believing that cheetahs will someday gain wings and fly, and that tigers will one day turn into giant birds. No rational person could ever accept such an irrational claim.

The fact is that flies have an utterly immaculate flight system. While human beings cannot flap their arms even 10 times a second, an average fly is able to beat its wings 500 times a second. In addition, both its wings beat simultaneously. The slightest discrepancy between the movements of the two wings would cause the fly to lose balance. Yet no such discrepancy ever arises. The biologist Robin Wootton describes the perfection in the fly's wing:

The better we understand the functioning of insect wings, the more subtle and beautiful their designs appear . . . Structures are traditionally designed to deform as little as possible; mechanisms are designed to move component parts in predictable ways. Insect wings combine both in one, using components with a wide range of elastic properties, elegantly assembled to allow appropriate deformations in response to appropriate forces and to make the best possible use of the air. They have few if any technological parallels—yet. (Robin J. Wootton, "The Mechanical Design of Insect Wings," Scientific American, Vol. 263, November 1990, p. 120.)

If the Darwinists' claims were true, then a great many other animals famed for their high speed also would chase flies, and lions, leopards, cheetahs and horses should also one day have grown wings and started flying. Darwinists adorn these claims with scientific and Latin terminology, and millions of people naively believe them. The fact is, though, scientific findings openly and clearly reveal the invalidity of evolutionist claims. Not a single example of a living thing gradually acquiring wings has ever been encountered in the fossil record. Research reveals that any such transition is impossible.

- Fossil records refute evolution

- Darwin was mistaken: Species have never changed

- The claim of intermediate-form fossils is a deception

- The fossil record verifies creation: stasis in the fossil record

- The coelacanth silenced the speculation concerning fossils

- The starting point of punctuated equilibrium

- Conclusion

- Fossil specimens of land-animals

- Fossil specimens of sea creatures

- Fossil specimens of sea creatures -2-

- Fossil specimens of birds

- Fossil specimens of plants

- Fossil specimens of plants -2-

- Fossil specimens of plants -3-

- Fossil specimens of insects

- Fossil specimens of insects –2-