|

Two documentaries called Dinosaur Dealers have been broadcast on National Geographic TV. These dealt with the trade in fossils and fossil smuggling, and described the adventures of a paleontologist who followed in the tracks of a number of stolen fossils, or fossils smuggled out of Australia. The trail was followed detective-style, and the program showed the negotiations carried out in order to trap the smugglers. In this way, the impression wasgiven that National Geographic is an idealistic body, chasing hot on the heels of smugglers and striving with all its might to destroy this illegal trade. However, the TV channel failed to mention that just a few years ago it too was involved in smuggling an Archaeoraptor fossil (and the fraud that accompanied it). In fact, it said not a word about it.

Let us recall the details of that smuggling operation.

Archaeoraptor liaoningensis was a forged dino-bird fossil. The remains of the creature, alleged to be an evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds, had apparently been unearthed in the Liaoning area of China and were published in the November 1999 edition of National Geographic magazine.

Stephen Czerkas, an American museum administrator, had bought the fossil from the Chinese for $80,000, and then showed it to two scientists he had made contact with. Once the expected confirmation had been received, he wrote a report about the fossil. Yet Czerkas was no scientific researcher, nor did he hold a doctorate of any sort. He submitted his report to two famous scientific journals, Nature and Science, but they both declined to publish it unless it was first vetted by an independent commission of paleontologists.

Czerkas was determined to have this fantastical discovery published, and he next knocked at the door of National Geographic, known for its support of the theory of evolution.

Under Chinese law it was definitely forbidden to remove fossils unearthed within its borders from the country, and fossil-smuggling could be severely punished, even by death. Despite being well aware of this, National Geographic accepted this fossil which had been smuggled out of China. The fossil was presented to the media at a press conference staged in the National Geographic headquarters in October 1999. An illustrated seven-page article describing the dino-bird fairy tale formed the cover story in the November edition of National Geographic magazine. Moreover, the fossil was exhibited in the National Geographic museum, where it was presented to millions of people as definitive proof of the theory of evolution.

|

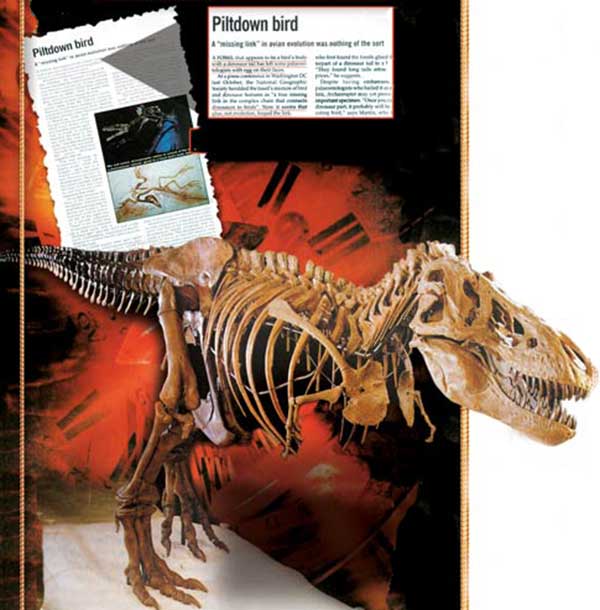

Thus, the Archaeoraptor fossil is similar to the earlier Piltdown Man fraud committed by evolutionists. Archaeoraptor was even described under the headline "Piltdown Bird" in the well-known magazine New Scientist. The report states that Archaeoraptor was formed by adding the tail of a dromaeosaurus, a genuine dinosaur, to a bird fossil, and that this was a fraud perpetrated in the name of science. |

The truth emerged in March 2001: no such intermediate species as Achaeoraptor had ever existed. Computer tomography analyses of the fossil revealed that it consisted of parts of at least two different species. Archaeoraptor was thus dethroned, and took its place alongside all the other evolutionist frauds in history. Darwinism—whose claims have never been empirically verified in the past 150 years—was once more associated with specially manufactured fossil forgeries.

As we have seen, National Geographic was once party to that very fossil-smuggling which it now purports to oppose. Naturally, the fact that in its latest documentaries it devotes space to bringing fossil smuggling out into the open may be regarded as a positive sign that it will not tolerate similar abuses in the future. However, if the TV channel does oppose fossil-smuggling, then it must also deal with such well-known smuggling incidents as Archaeoraptor in its programs. No matter how much of a violation of its Darwinist broadcasting policy it might be, admitting its past mistakes and taking the side of the truth would be commendable behavior in the sight of all its viewers.