Sayyid is the title given in Islamic culture to people descended from Hassan (ra), grandson of our Prophet (saas) through his daughter Fatima (ra). Individuals descended from Husayn (ra), the Prophet’s (saas) other grandson, are known as sharifs.

The Arabic word “sayyid” corresponds to the English words “lord, chief, or leader.” In the Hadith, the term is used in the sense of “tribal chief or eminent members of a community.” Sayyids are also known as “habib,” “emir,” or “mir” in various Islamic lands. The great Islamic scholars Imam al-Bukhari and al-Tirmidhi say that this title was first used by the Prophet (saas) in reference to Hassan (ra). Rasul al-Akram says that when sitting on the pulpit one day, he pointed to Hassan (ra) in one of the rows and said: “This [grand]son of mine is a sayyid. It is to be hoped that through him Allah will establish peace between two Muslim sects.” (al-Bukhari, Sulh, 9; Fada’il al-Ashab, 22; Tirmidhi, Manaqib, 31) In another hadith, our Prophet (saas) said: “Hassan and Husayn are the two sayyids of the young people of Paradise.” (Tirmidhi, Manasik, 31)

The Arabic word “sayyid” corresponds to the English words “lord, chief, or leader.” In the Hadith, the term is used in the sense of “tribal chief or eminent members of a community.” Sayyids are also known as “habib,” “emir,” or “mir” in various Islamic lands. The great Islamic scholars Imam al-Bukhari and al-Tirmidhi say that this title was first used by the Prophet (saas) in reference to Hassan (ra). Rasul al-Akram says that when sitting on the pulpit one day, he pointed to Hassan (ra) in one of the rows and said: “This [grand]son of mine is a sayyid. It is to be hoped that through him Allah will establish peace between two Muslim sects.” (al-Bukhari, Sulh, 9; Fada’il al-Ashab, 22; Tirmidhi, Manaqib, 31) In another hadith, our Prophet (saas) said: “Hassan and Husayn are the two sayyids of the young people of Paradise.” (Tirmidhi, Manasik, 31)

Prophet Muhammad (saas) also imparted the glad tidings that the blessed Mahdi (as), who will appear in the End Times and who is awaited with great joy and expectation by all Muslims, will also be descended from him:

“We are the sayyids of the people of Paradise, the sons of Abd al-Muttalib. Me, Hamza, Ali, Jaffar, Hassan, Husayn, and the Mahdi.” (Ibn Majah, 34)

Muslims Have Always Treated the Sayyids with Great Love and Respect

Muslims have always extended the love and affection they feel for the Prophet (saas) to the sayyids. Due to their deep love for Prophet’s (saas) family, Muslims have always held the descendants of his grandchildren in the highest regard. Sayyids have enjoyed a privileged position in worldly treatment in almost all Islamic countries, and efforts have been made to bestow various advantages on them.

The most obvious proof of this is how, in the past, special bodies were concerned with their affairs and that the person at the head of these institutions (the naqib al-ashraf) was regarded as having one of the highest ranks.

How Did the Sayyids Spread to Different Lands?

In the age of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs, Muslims traveled to many lands to spread the message of Islamic moral precepts. These missionary journeys intensified considerably during the time of Umar (ra) and Uthman (ra). There were many sayyids among those who set out to spread the Qur’an’s moral values to humanity. They generally settled in the regions to which they traveled and assimilated with the local inhabitants.

However, like other Muslim emigrants, the great majority of the sayyids who emigrated left Arabia because of the strict policies of the Umayyads, who assumed power after the age of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs.

Following the martyrdom of Hassan (ra) and Husayn (ra), their migration accelerated still further, to places within the Islamic state’s borders of the time: the Maghreb (Morocco), the Caucasus, Transoxiana, Khurasan, Tabaristan, and Yemen. Thanks to this migration, many dynasties were founded, such as the Idrisids in Morocco, the Sulaymanis in Yemen and the Zaydis, in Iran.

Many sayyids took up residence in the Mongol and Turkish states and assimilated with the local peoples. Sometimes they even took their places among the founders of other states, such as the Nogay dynasty, which established itself in the Caucasus.

The Sayyids Also Migrated to Turkey

As the sole heir of the Ottoman Empire, the longest-lived and largest Turkish Islamic state, Turkey is one of the countries most intensively settled by sayyids. Today, they live in many parts of the country, but especially in Ankara, Siirt, Sanliurfa, Erzurum, Elazig, Erzincan, Adana, and Igdir. The majority of them settled in Anatolia during the first sayyid migrations. However, the migratory trend to Turkish lands continued.

During the Ottoman-Russian and Russian-Caucasian wars in particular, many sayyids living among the Caucasians migrated and settled in central Anatolia. Among them was the family of Ömer Bey, the grandfather of Adnan Oktar.

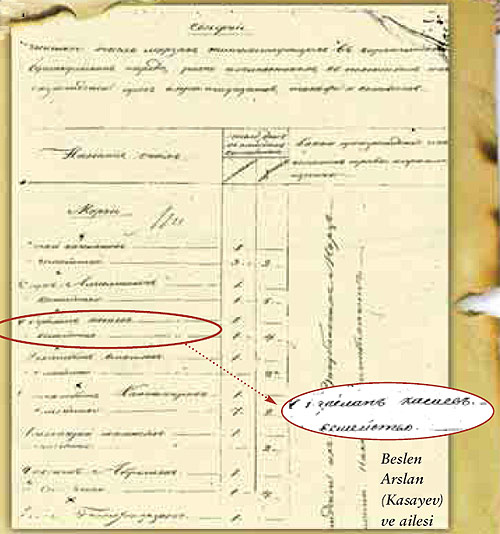

The origins of Beslen Arslan Kasayev, Ömer Bey’s grandfather, go back to the Nogay dynasty. This family is also known as the Arslanogullari (the sons of Arslan) and is one of the twenty-one sayyid families whose names appear in a document prepared for the Caucasus governorship in 1827. In 1902, the family left the Caucasus and settled in Bala, a town in Ankara province. (*)

Information concerning the surnames and family members of the Nogay sayyids living in the Kara Nogay and Yediskul region.

| Sayyid families were known to and recognized by the people in the regions where they lived. These families constituted a community, recognizing and acting as guarantors for one another. |  | *Photocopy of an original document dated 17 July 1827 in the Russian Federation Stavropol Federal Archive. Archive No. 48, Vol. 2, File No. 853. |

Photocopy of an original document dated 17 July, 1827, in the Russian Federation Stavropol Federal Archive. Archive No. 48, Vol. 2, File No. 853.

| Family Members | ||

| Name and Family | Male | Female |

| 1. Nugay Kaplanov and family | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Yusuf Ali Aysoltanov and family | 2 | 5 |

| 3. Beslen Arslan Kasayev and family | 2 | 4 |

| 4. Han Muhambet İsmailov and family | 3 | - |

| 5. Muhambet Kantemirov and family | 8 | 9 |

| 6. Mengligirey Tilenchiyev and family | 3 | - |

| 7. Yanseyit Abdullayev and family | 2 | 4 |

| 8. Gazı İnal Batırburzayev and family | 5 | 7 |

| 9. Hayati Ahmetov and family | 3 | 3 |

| 10. Nemin Yasenbi Adjiyev and family | 8 | 5 |

| 11. Alibey Mamayev and family | 3 | 3 |

| 12. Musousov and family | 2 | 3 |

| 13. Alibek Soltanaliyev and family | 4 | - |

| 14. Bekmurza Karamurzayev and family | 3 | 2 |

| 15. Aslangirey Temirhanov and family | 3 | 3 |

| 16. Alibey Temirov and family | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Ali Mamayev and family | 3 | 1 |

| 18. Beymurza İsterekov and family | 4 | 3 |

| 19. Tausultan Temirhanov and family | 7 | - |

| 20. Mamay Arslanov and family | 1 | - |

| 21. Magomet Utepov and family | 3 | 3 |

| Total number of individuals | 75 | 61 |

This historical document contains details of the identities and families of the Nogay sayyids living in the Kara Nogay and Yediskul regions. The record concerning Beslen Arslan, the grand grandfather of Mr. Adnan Oktar and his family appear under No. 3 in the list. Mr.Adnan Oktar’s grandfather, Ömer Bey, was born in the Caucasus and settled in the Ankara township of Bala in 1902. Ömer Bey’s father was Haci Yusuf, and Haci Yusuf’s father is Beslen Arslan (Kasayev) recorded as a sayyid in the Russian archive.

Above: Marriage certificate of Mr. Adnan Oktar’s father, Yusuf Oktar Arslan.

Mr. Adnan Oktar’s father's surname is mentioned as Arslan in the official records. This surname appear in the Russian archive.

The Esteem Attached to the Sayyids in Turkish Islamic Culture

Soldiers were viewed as the most respected and prominent individuals in Turkish Islamic states. Officials and the public regarded the sayyids as members of the military class and held them in high esteem. The state exempted them from all tithes and taxes, and awarded them pensions so they would not have to suffer any financial difficulty.

On occasion, local officials acted irregularly and attempted to extract taxes from sayyids and sharifs. However, the central authorities forestalled such actions. Many firmans (decrees) of the Sultans directed that the Prophet’s (saas) descendants should not be mistreated and that they should be treated with the highest respect. Many Ottoman historians, such as Evliya Celebi, said that the sayyids were generally modest and had the kind of moral values that made them reluctant to make their status obvious. Over the course of time, however, individuals did emerge who sought to profit from the status of being a sayyid.

As the number of these false sayyids (known as “mutasayyid”) increased, the Ottoman Empire took steps to prevent the serious decline in its tax revenues and to protect the rank of sayyid. Detailed inquiries were carried out into everyone claiming to be a sayyid. An institution known as the naqib al-ashraf was set up to record and preserve the pedigrees and genealogies of the sayyids and the sharifs. This body was first set up during the reign of Sultan Celebi Mehmet, dissolved in the time of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, and then reestablished during the reign of Sultan Beyazid II.

Special officials, known as “naib” (the name given to representatives of the naqib al-ashraf, who lived in Istanbul and was regarded as chief of the sayyids) were appointed to provinces to expose false sayyids. These officials maintained inspection records, based on existing evidence of sayyid status. These records would make it easy for the central authority to determine whether any of the individuals pretending to sayyid rank were real sayyids. The head of this institution occupied an important place at the Ottoman court. On a sultan’s accession to the throne, he would be the first to declare his loyalty to the sultan. During official Ottoman state ceremonies, he would open the ceremony with a prayer when the sultan left the reception room and sat on the throne.

At both the coronation and other official state ceremonies, the sultan would rise to his feet out of respect when congratulated by the naqib al-ashraf. Titles unique to this person were employed in official correspondence.

After this person, the sayyids’ most important leaders were people who bore the title “alamdar” (standard-bearer), who left the palace together with the army during campaigns and carried the “Standard of the Prophet.” The naqib al-ashraf and other sayyids and sharifs would participate in the standard ceremonies by reciting the takbir and reciting prayers for the Prophet (saas) on the departure and return of the Standard of the Prophet.

Most of the sayyids living in Anatolia were members of the ulama (religious scholar) class and served as imams, scribes, religious judges, local registration officials, and madrassah instructors.

Under the Ottomans, it was enough for one’s paternal line to extend back to Prophet Muhammad (saas) in order to be regarded as a sayyid. It was also considered possible to be a sayyid through the maternal line alone, which was not common in other Islamic states. Under the Ottoman Empire, sayyids who were the descendants of the Family of Abbas (the line of the uncle of the Prophet [saas]) were also held in high regard.

REFERENCE:

1- Y.N. Kusheva, T.H. Kumikova (collectors), Kabartay-Russian Relations in the XVI-XVII Centuries: Documents and Correspondence, vol. 1, (Moscow: 1957).